Transects, quadrats – huh?!? What’s all this jargon about – and how do I use the things, anyway?

If you’ve ever considered a life as a marine biologist you might like to take a short taster first. It’s an over-crowded profession and if it’s not going to be right for you it’s as well to find out before you spend all that time studying. I thought it would be interesting to see what it was all about, so I signed up for two weeks with Kenna Eco-Dive in L’Escala, north-east Spain. There are lots of other places you can go – just type “Marine conservation” into your browser for a long list – though some of them charge pretty high fees.

Kenna is based just inside the Medes Islands marine protected area. Gaye Rosier of Kenna has worked with Spain’s Silmar Project since 2009, studying 12 key Mediterranean indicator species, and with various other agencies investigating other species, debris, and the marine environment. She’d been looking for seahorses for years before finding them last year; now she’s identified 28.

Finding them isn’t easy. There’s a large area of sand and algae to search, which is where the transect comes in. You lay a 30 metre measuring tape (the transect) on the sea-bed and then move slowly along either side of it, searching the algae, until – hopefully – you spot something for Gaye to log. Then you pick it up and repeat the process; and again; and again; our longest seahorse-hunt lasted 92 minutes. Using this method we saw 12 seahorses altogether over the two weeks.

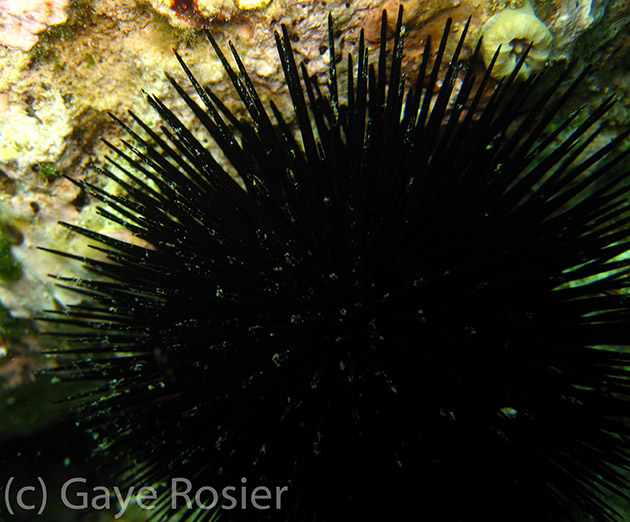

We used the transect again, over rocks and through Posidonia grass, to count sea urchins. There are three varieties and Gaye counts them because black urchins like warmer water than the other two (rock and violet), so increasing numbers of black urchins suggest increasing water temperature.

A quadrat is a square, in this case made of light plastic piping with 50 cm sides. You put it over, say, a patch of Posidonia, and count the number of shoots in the enclosed patch. This gives an approximation of the number of shoots in the whole area.

Doing these counts regularly, and logging the results, gives a view of changes that may be occurring either in the short term (storm damage, for example) or over the long term, which helps marine biologists develop strategies for conservation. These could be as simple as providing permanent mooring buoys so that boat-owners don’t drop anchor in the (protected) Posidonia beds.

If you like your diving speedy or scenic, this probably isn’t your ideal holiday. If you want to dive somewhere different every day, forget it – the whole point is to see how things change and what’s there today that wasn’t yesterday, or vice versa. If you’re really interested in all the wide variety of marine life, and in helping ensure it stays alive and well, this is a great way to spend a couple of weeks. And if you want to know whether you could hack life as a marine biologist, it’s a cool way to start.