The BBC Natural History Unit is famed for its natural history and wildlife documentaries including The Blue Planet, Planet Earth and most recently a three-part series called Shark. The programmes that this department of the BBC produces are well known for their stunning videography, factual content and non-sensationalist approach. With that in mind, Shark has been highly anticipated.

‘A major wildlife series on the sharks of the world with over thirty species filmed, showing how they hunt, intricate social lives, courtship, growing up and the threats they face.’ (Source BBC Website)

The release of Shark couldn’t have come at a better time when you consider the global status of shark and ray populations. There are over 500 species of shark and 500 species of ray in existence today and yet a quarter of those species are threatened with extinction, according to The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Humans kill approximately 100 million sharks every single year and over 70 percent of those killed are destined for the shark fin soup trade.

I hoped this new series would delve deeply into the plights that sharks face, shine a light upon the latest work being done to protect sharks and rays and provide a welcome alternative to the sensationalist programmes that have been aired within Discovery’s annual SharkWeek. As an aside, Discovery’s SharkWeek has been widely criticized after their 2014 week of programmes and they lost millions of viewers – perhaps as a result of their sensationalist rather than factual approach?

I had also hoped the BBC would use this opportunity to focus on and discuss the irrational fear humans have of sharks. Yes they are predators but they do not need to be feared or demonised in the ways humans have done so for years with their negative media coverage. We are at a time when the infamous movie Jaws should be a distant memory and a reminder of the power that negative media can hold. Surely the next generation deserves not to fear sharks the way the Jaws generation did? During our shark conservation talks around the world we find that the youngest children we present to, ages 4 to 7, are fascinated with sharks and have no fear of them. However, those aged 8 upwards have often already begun to fear sharks despite having no experience of sharks themselves. The difference between those age groups is clear; the older children are being exposed to the media and Internet with its wealth of sensationalist and fictional ‘shark attack’ videos and articles.

So, did BBC Shark live up to its hype and provide all that I (and no doubt other shark enthusiasts) had hoped for? Yes, in some ways it did but it was also sadly lacking.

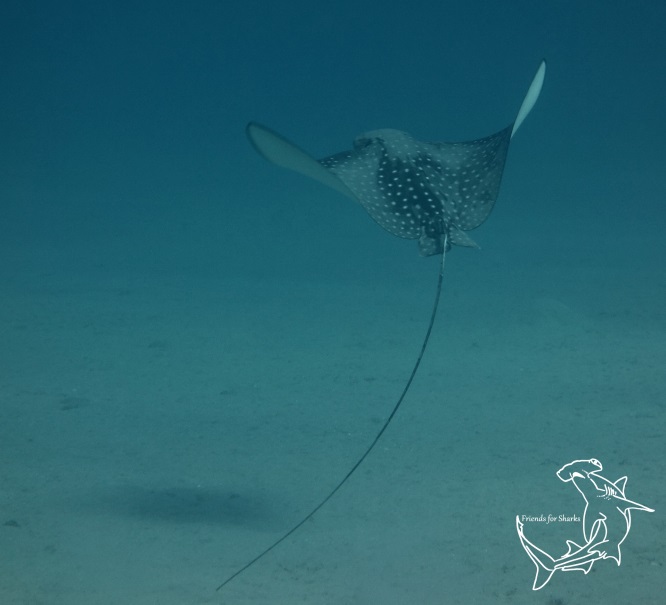

On the positive side, the videography was ground-breaking and left me speechless at times. I had a distinct urge to be back in the water diving with sharks as soon as possible. It was fantastic to watch the BBC sharing footage of the lesser-known shark species such as the Greenland, Epaulette and Lemon sharks and they spent a considerable amount of time discussing the social lives and behaviours of sharks and rays. Thankfully the BBC did talk about the plight of sharks by mentioning shark fin soup and the recent shark cull in Western Australia. The series also discussed medical and technological advances related to sharks.

I was however very disappointed by the musical score. The tone of the composition had threatening undertones, hints of fear and was on the dark side whenever a shark swam into view, which was of course often. The narration was at times suggestive of sharks being ‘monsters of the deep’ and something to be feared. There was a distinct pandering to the public’s appetite for sensationalist programming and it was not necessary at all. Without intending to, the BBC has pushed the common belief that sharks should be feared. By contrast, the composition that accompanied the ray footage was beautiful, relaxing and inspiring. Would it have been too much to ask for similar music to accompany the grace of sharks?

I was also disappointed that the BBC didn’t dig deeper into the plight of sharks and really highlight the diversity of threats they face. The majority of the public are not aware of the extent of shark culls, lethal shark nets and shark poaching (to name but a few) and perhaps do not understand how the choices they make can and do affect shark populations. Most people, when they understand what is happening to the oceans, are horrified and want to help. The BBC had an ideal opportunity to explain what each of us can do to help conserve sharks; from simple lifestyle changes to spreading awareness. They also had an opportunity to highlight the work of global conservation organisations and individuals that are working hard to protect sharks and rays for future generations.

Whilst the BBC discussed important scientific research being done around the world to understand and conserve both sharks and rays, science does not have all of the answers on its own. I would have liked to see a focus on conservation and educational initiatives alongside the scientific work being done. Episode 3 contained footage of the magnificent Great White sharks and Cape Fur seals of South Africa and yet it included a fact that has been known for years; that this species of shark hunts at dawn and dusk. It is common sense that those are the times of day to stay away from surfing areas that Great White sharks patrol. I was quite frankly surprised to hear that simple and well known fact being shared as if it were a new discovery. I had high hopes at that point that the BBC would have gone on to highlight the incredible work being done by Cape Town’s Shark Spotters. Their educational Shark Spotting Programme manages interactions between sharks and water-users within South Africa. The Shark Spotters are leading the way with non-lethal methods of control and yet it was nowhere to be seen.

By contrast, cast your eyes and ears back to 1995 and there is a true gem of a documentary produced the BBC. The BBC Wildlife Special about Great White sharks may now be considered dated but it is absolutely one to watch. It is narrated by David Attenborough and both the videography and musical score are stunning. There is no fear-mongering, no threatening music or over dramatisation and there is a strong focus on the plight of sharks. The combination of the footage of the sharks and the score is a match made in shark heaven and it is what I had hoped for from BBC Shark. I know which programme I will be choosing to watch again and it is one I hope many more people will share and enjoy.