Fishing is as emblematic to Canada as ice hockey. It’s also a way of life with a long tradition in coastal Indigenous communities. But since European contact, it’s been all but eliminated as an economic development opportunity for them.

As Canada struggles to come to terms with reconciliation, court cases are helping define what Indigenous rights and title mean in day-to-day life. If the federal government is serious about its commitment to a new and respectful relationship with Indigenous peoples, it should set the tone through policies that address historic injustices, such as in commercial fishing practices.

It’s been seven years since the court recognized the Nuu-chah-nulth’s right to fish for a living. Despite losing two appeals and being given years to work through the court’s ruling, Canada has yet to negotiate or put in place court-mandated fishing plans. These Vancouver Island communities are tired of waiting. In September, hereditary chiefs dismissed Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s regional director-general from a meeting, telling her not to return until Canada is ready to implement the five nations’ right to catch and sell fish.

This and one other court ruling acknowledge an Aboriginal right to commercial fisheries beyond already established food, social and ceremonial fisheries. Nuu-chah-nulth rights to sell fish apply to any fish species in the territory except geoduck. The right can be restricted for valid conservation reasons, as the Nations’ fishing plans reflect. But while Canada’s courts recognize rights-based fisheries, those rights are not respected. The federal fisheries department approved minimal harvests of gooseneck barnacles and chinook salmon, but turned down everything else the Nuu-chah-nulth proposed.

The court case examined the Nuu-chah-nulth’s pre-contact way of life alongside current West Coast fishery regulations. Fishing and fisheries resources trading were recognized as a practices integral to the distinctive cultures of pre-contact society. The Nuu-chah-nulth were acknowledged as a fishing people who depended almost entirely on ocean and river resources for food and economic trade.

Over the past 20 years, many commercial fisheries in Canada have become more ecologically sound, yet economic benefits rarely go to communities living near the resources. Selling marine resources is an important community development opportunity for Indigenous peoples who face erosion of traditional fishing culture alongside limited job opportunities. A 23-kilogram halibut, for example, fetches about $500. It doesn’t take many to make a huge economic difference for these small communities. But about 80 per cent of the halibut industry’s annual allocation is not fished by those who actually own the quota. Seventy per cent of the halibut’s value goes to the leaseholder, with only 30 per cent for the fishing operation. Most of the price to harvesters bypasses coastal communities, often ending up outside of Canada.

Canada’s fisheries policies benefit industrial operations over . While redeveloping Aboriginal commercial fisheries alongside existing fisheries won’t be easy, it’s the next evolution. Halibut, salmon, crab, prawn, sablefish and herring catches, of particular interest to the Nuu-chah-nulth, are fully allocated. But the Nuu-chah-nulth were the first to have a commercial fishery and the court found it was unfairly taken from them. So it must be restored.

Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission called on all of society to embrace reconciliation, which is guided by the tenets of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Article 20 says, “Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain and develop their political, economic and social systems or institutions, to be secure in the enjoyment of their own means of subsistence and development, and to engage freely in all their traditional and other economic activities.” Despite mixed support from federal and provincial governments for UNDRIP, the commission emphasized its importance for reconciliation to succeed.

Indigenous peoples have been denied their share of marine resources for too long, watching as commercial and recreational fisheries profit from resources on their waters while their boats sit idle. For cultures built on sharing and selling those resources, it’s a bitter pill and a threat to cultural survival. It’s time for a new relationship built on co-management and equitable division of ocean resources, guided by a shared commitment to ocean conservation. Reconciliation in action would mean restoring the rights of the Nuu-chah-nulth and other Indigenous peoples to fish for a living.

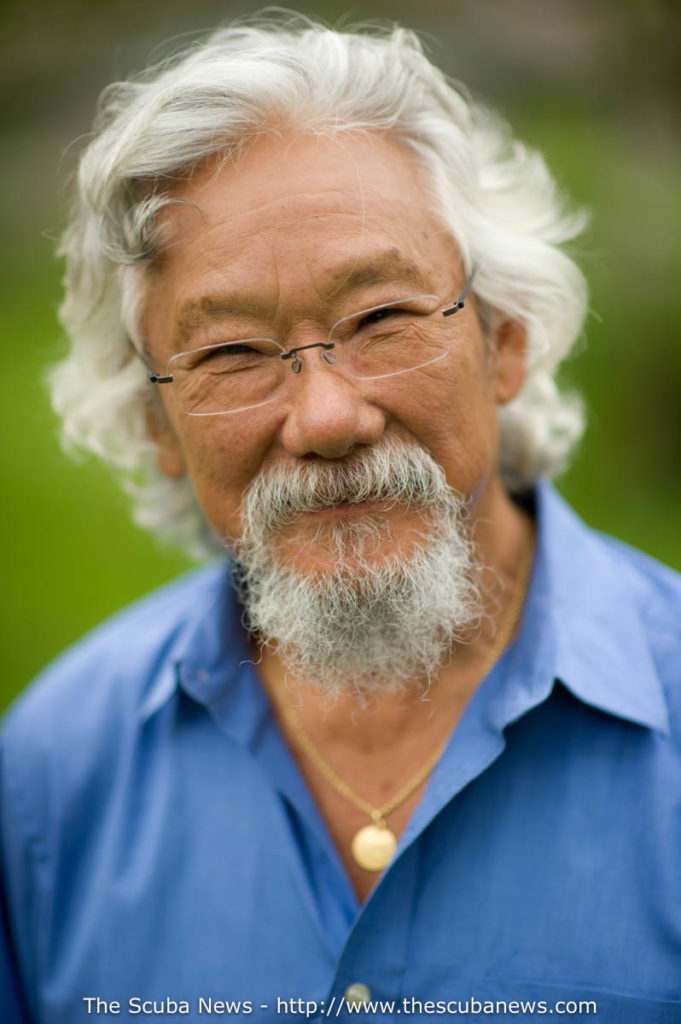

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation senior communications specialist Theresa Beer.