Most of us rarely think about concrete, but it’s the foundation of modern society — from roads, buildings and bridges to the economy, political power and crime. We use more of it than anything except water.

Concrete has been a great driver of human progress. It’s allowed us to build up instead of out, made transportation and trade easier, protected us from the elements and even disease, and spurred economic growth and job creation — as well as population growth.

But it’s one of many innovations we adopted wholesale without fully understanding the consequences. Producing and transporting it emits enormous amounts of greenhouse gases. It also destroys natural ecosystems — including carbon sinks like forests and wetlands — and consumes huge amounts of water and other resources. Even global sand supplies are dwindling, thanks to its use in concrete. And it doesn’t always do as good a job as nature at protecting us from natural forces. Massive barriers sometimes offer less protection against tsunamis and flooding than the coastal mangrove swamps they displaced.

Even the recent scandal facing Canada’s government has concrete at its base. As one of Canada’s largest engineering and construction companies — employing 50,000 people through offices in over 50 countries and operations in more than 160 countries — SNC-Lavalin uses a lot of concrete. Infrastructure projects are important to industry and governments. They provide employment, keep GDP and the economy growing and offer “concrete” proof that progress is being made.

But, as the Guardian points out, “As well as being the primary vehicle for super-charged national building, the construction industry is also the widest channel for bribes. In many countries, the correlation is so strong, people see it as an index: the more concrete, the more corruption.”

SNC-Lavalin, which has already been sanctioned by the World Bank for bribery and corruption, faces similar charges at home. But as a major Quebec-based employer with its hand in some of the country’s largest infrastructure projects, it’s seen by provincial and federal governments as too important to fail.

One problem is that we’re basing economic decisions and government policy on economic systems that were designed when natural resources were abundant and built infrastructure was lacking. The opposite is now true, but to satisfy an appetite for continuous, rapid economic growth, we construct more roads, bridges, parking lots, dams and buildings without considering alternatives for progress and building materials.

To a large extent, it’s about maintaining our fossil-fuelled car culture. And it could get worse as developing nations scramble to catch up, building their own massive infrastructure projects and facilitating increased automobile use.

The Carbon Disclosure Project estimates that cement production produces six per cent of global emissions, slightly behind steel production. Concrete, made from cement, is second only to coal, oil and gas for emissions. According to a Guardian article, “Its wider effects are even more problematic, as the built environment accounts for more than a third of the world’s carbon emissions.” Shipping the heavy product also emits greenhouse gases, and the industry accounts for 10 per cent of global industrial water use.

With urbanization, population growth and economic development rapidly increasing concrete use, ecosystem destruction and greenhouse gas emissions will continue to rise. A Carbon Disclosure Project report, “Building Pressure”, concluded, “Cement companies urgently need to more than double their emissions reductions or risk missing climate goals.”

It noted that regulation and technological innovation are key, not just to reduce emissions but also to find ways to capture and sequester them.

Although the report notes that carbon capture and storage “is an important technology for creating low-carbon cement,” progress has been limited, in part because the technologies haven’t yet proven to be viable. Carbon pricing and regulation, along with use of alternative fuels sourced from organic waste collection, are showing greater benefits.

We also have to find alternatives to massive concrete-based infrastructure projects and the economic systems that drive them. Reducing dependence on private automobiles could help curtail construction of the widespread infrastructure required to support them. Using renewable materials like wood for some construction is a step but comes with its own problems. Better concrete recycling and diversifying energy sources to reduce emissions from production and transport are also important.

It’s time for concrete solutions.

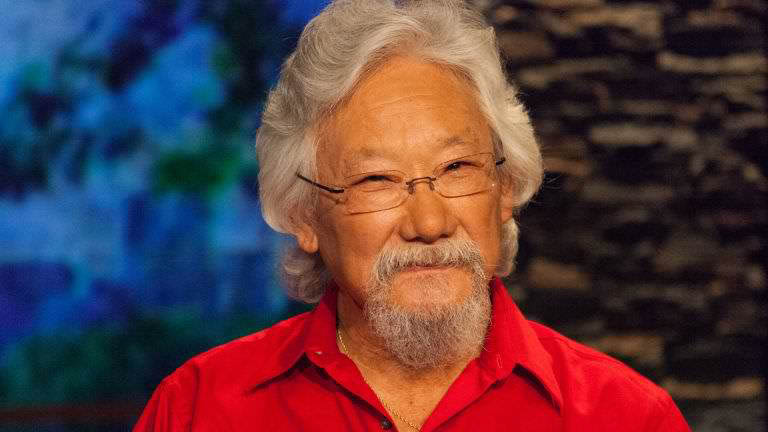

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Senior Editor Ian Hanington.