A popular sign at climate marches reads, “System Change, Not Climate Change.”

What does system change look like? Environmental crises such as climate disruption and plastic pollution have led many to suggest it means moving from a perpetual-growth economic system to a circular one, reforming land management to co-management with Indigenous Peoples and shifting from extractive, polluting energy sources to renewables.

Our society is constantly evolving its ideas and approaches. There are no doubt systems changes that have not yet been dreamed of. But in considering how to make systems more equitable and sustainable, one change underpins all others: a change in our relationship with nature.

The Western relationship is one of dominance. Government agencies that manage ecosystems are called “natural resource” departments, inferring that nature is a resource for human exploitation. Every inch of the planet has been petitioned for human ownership. The mainstream view is that nature is property, not a living, generative force. It’s a perspective upheld by our legal systems. People “own” farm animals, we can legally deplete the ocean of fish, and when private companies drain public aquifers for profit, communities must go to court to challenge them.

Under Western legal systems, the concept of “personhood” includes rights, powers, duties and liabilities. In many countries, corporations are recognized as having legal “personhood” and accompanying rights as well. Recently, as a reflection of Indigenous leadership and world views, the legal rights of personhood have in some instances been extended beyond people and corporations to nature itself.

In New Zealand, after centuries of advocating for a river they identified as their life force, the Māori negotiated a treaty settlement with the government recognizing that the Whanganui River, or Te Awa Tupua (which refers to the entire river system “and all its physical and metaphysical elements”), has the rights of a legal person.

According to David Boyd, author of The Rights of Nature: A Legal Revolution that Could Save the World, this recognition, formalized in law in early 2017, means that, “In short, the Whanganui River is no longer owned by humans but by itself, Te Awa Tupua.” The law puts the interests of the river first and contains safeguards against privatization and harm, and enables citizens to sue government and corporations on the river’s behalf.

When the legislation passed — with support from all political parties — New Zealand Green Party co-leader Metiria Turei said, “Our environment, however we want to describe it, is our ancestor and from where we come, and, therefore, we owe our environment everything — our life, our existence, our future. The law slowly is starting to find ways — clumsy and not perfect by any means, but it is slowly trying to find ways to understand that core concept.”

New Zealand offers an introduction to an unfolding story. Numerous initiatives worldwide are aimed at bestowing legal personhood and accompanying rights to nature, including rivers, forests and mountains. New Zealand has since given the same rights to a 2,000-square-kilometre former national park known as Te Urewera and to Mount Taranaki.

Unfortunately, in addition to being clumsy, some of these laws contain loopholes government can use to override nature’s rights. Enforcement in many regions has also proven to be a challenge, especially when changes to mainstream resource extraction practices are required.

Some Indigenous experts also point to significant limitations with the Western concept of “legal personhood,” especially when viewed alongside Indigenous laws. Anishinaabe-Métis lawyer and law professor Aimée Craft said in an email, “Indigenous laws tell us that nibi (water) is living — it has life and can take life. Recognizing the agency and spiritedness of water is distinct from the concept of legal rights of water or personhood. Indigenous legal orders can provide insight into the mechanisms by which we can honour our responsibilities to water, in all of its forms.”

The Western relationship with nature has led to climate and biodiversity crises. System change does not happen overnight. But it has begun, and this is a source of hope. As many Indigenous Peoples worldwide have articulated, we come from nature and are kin to it. We don’t own it. To develop news systems of sustenance and respect, we must move collectively beyond seeing nature as merely something to exploit.

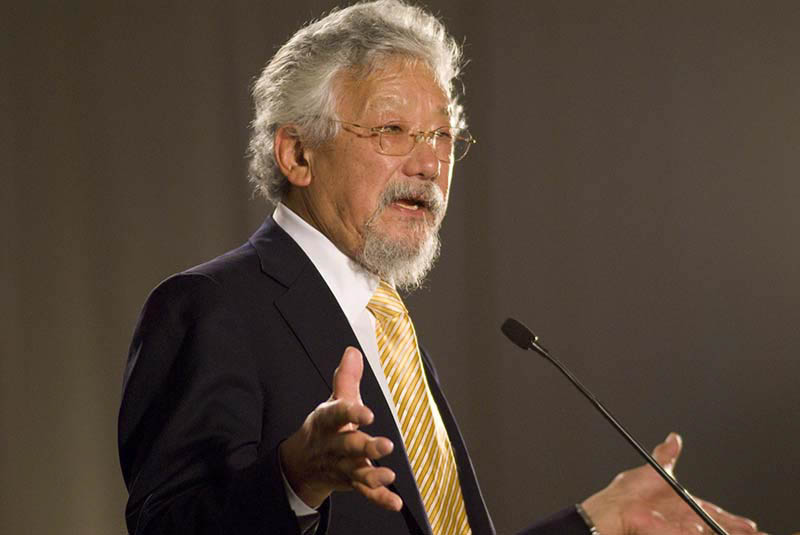

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Boreal Project Manager Rachel Plotkin.