Diversity is strength. That’s true in nature and human affairs.

But recent painful events have shown society has yet to grasp this. The appalling deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Toronto’s Regis Korchinski-Paquet, Chantel Moore from Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation and many others — all at the hands of those tasked to serve and protect — have ignited awareness of the intense, often violent racial discrimination that continues to oppress Black, Indigenous and people of colour in Canada and the U.S.

The overwhelming call to end race-based discrimination demands we take stock and action. This needs to include an examination of how environmental harm disproportionately affects vulnerable populations and marginalized communities.

Canada’s main pollution-prevention law, the 269-page Canadian Environmental Protection Act, doesn’t include one mention of environmental justice, human rights or vulnerable populations.

Yet, in urban areas, 25 per cent of the lowest socio-economic status neighbourhoods are within a kilometre of a major polluting industrial facility compared to just seven per cent of the wealthiest. Income inequality in Canada also has a racial dimension. A 2019 analysis found racialized men earned 78 cents for every dollar non-racialized men earned, while racialized women earned 59 cents (non-racialized women earned 67 cents for every dollar non-racialized men earned).

About 40 per cent of Canada’s petrochemical industry operates within a few kilometres of Sarnia and the Aamjiwnaang First Nation, exposing community members to a range of harmful pollutants. Inuit in Canada’s North are at greater risk of economic losses and poor health as a result of climate change, with rapid Arctic warming jeopardizing hunting and many other activities.

Marginalized communities can also be more susceptible to insidious toxic exposures. For example, endocrine-disrupting chemicals, even at low levels, can interfere with hormone functioning. We’re all exposed to them in myriad ways, from food pesticide residues and personal-care product ingredients to textile treatments, product packaging and industrial air pollution. American researchers identified higher exposure levels in ethnic minorities and a corresponding higher disease burden. They hypothesize that cultural behaviours, consumption patterns and proximity of industrial facilities and waste sites could contribute to these disparities.

These are just a few examples. Unresponsive environmental policies systematically result in concentration of pollution risks — and inadequate access to environmental benefits — in disadvantaged Canadian communities.

This year, MP Lenore Zann introduced Bill C-230, the National Strategy to Redress Environmental Racism Act. It begins by recognizing that “a disproportionate number of people who live in environmentally hazardous areas are members of an Indigenous or racialized community. “The bill would require the environment minister to examine the link between race, socio-economic status and environmental risk, develop a strategy to redress environmental racism and report regularly on progress.

Canada should recognize the human right to a healthy environment in law, as most countries do, and legislate requirements to protect vulnerable communities from pollution and toxic substances.

Human rights impact assessment offers one approach to operationalizing environmental rights. It involves a process to identify, understand and address potential discriminatory effects of a proposed action, and a commitment to prevent adverse human rights impacts. Often this begins with something as basic as gathering data to better understand racial dimensions of potential effects.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development recommends it in its Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct for corporations operating abroad. Last year the UN Human Rights Council adopted guiding principles for human rights impact assessment for economic reform policies. A parallel process for environmental regulation could ensure everyonebenefits from environmental protection measures.

In their mandate letters, Canada’s ministers of health and environment were tasked with “better [protecting] people and the environment from toxins and other pollution, including by strengthening the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999.” In 2020, strengthening environmental legislation must incorporate human rights.

A human rights lens would remove a blind spot and hard-wire into the decision-making process a commitment to ensuring a healthy environment for all. It would help prevent environmental racism, while MP Zann’s bill aims to redress harm already done.

When Parliament resumes, MPs should prioritize passing Zann’s bill and amendments to strengthen the Environmental Protection Act, including environmental rights provisions. The unequal effects of environmental harm must be part of the reflection on systemic racism. But more is needed. Integrating a human rights lens into environmental decision-making is long overdue.

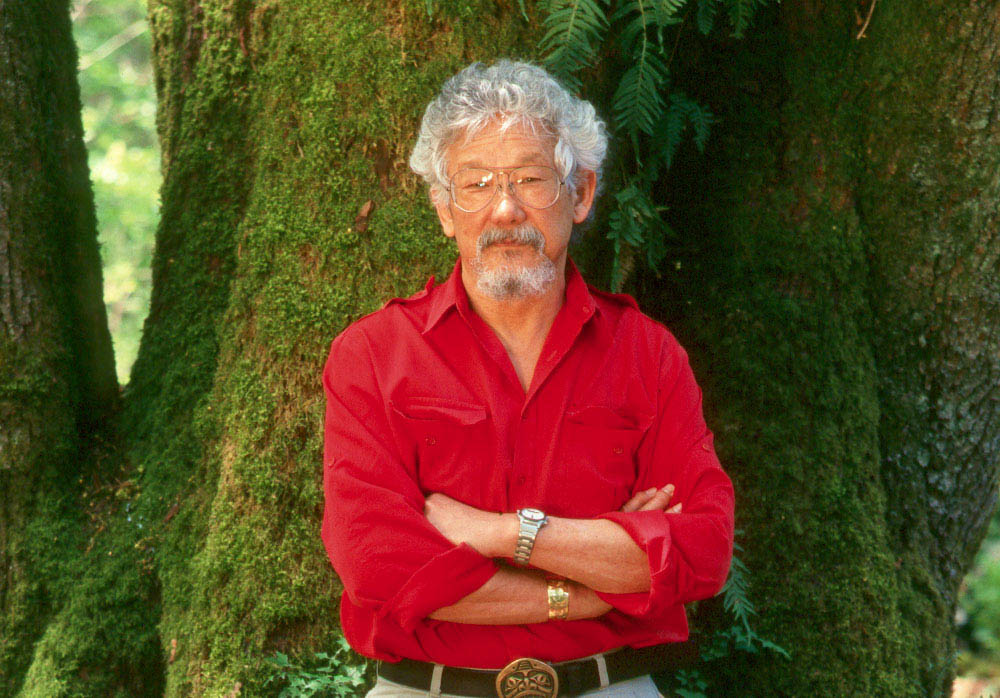

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Senior Policy Analyst Lisa Gue.