As natural environments and geographies shape language, so too does language shape the way we see nature and, subsequently, the impacts we have on the lands and waters that surround us.

Western culture and the English language primarily view nature as something owned by humans that can be exploited. That’s why Canadian agencies tasked with governing nature are referred to as departments or ministries of natural “resources.”

It’s not uncommon even for those who appreciate nature beyond its exploitative value to reduce it to a thing with monetary worth through language. For example, we refer to protected areas in Canada as “our” “national treasures,” “jewels” and “gems.”

Western science has also shaped the way we employ language to describe nature by advancing the reduction of living, functioning ecosystems to things best studied under a microscope. Recall Jane Goodall, admonished by her male academic compatriots for naming instead of numbering the chimpanzees she studied.

As Indigenous botanist and writer Robin Wall Kimmerer notes, “the English language is made up primarily of nouns, somehow appropriate for a culture so obsessed with things…. English encodes human exceptionalism, which privileges the needs and wants of humans above all others and understands us as detached from the commonwealth of life.”

Industry’s use of language brings the point home. Operators use words in novel ways to describe natural impediments to profit. Loggers call old growth trees that aren’t as profitable when logged as younger trees “decadent” — even though they provide habitat to at-risk species and have critical ecological functions. In oil and gas, vegetation above oil-shot rock — no matter how diverse or life-supporting — is called “overburden.” Some developers refer to off-limit conservation areas as “sterile.”

Nature’s vital life force is, to some extent, like Voldemort: that which cannot be named. As Nature Institute senior researcher Steve Talbot writes in “The Language of Nature,” words inevitably diminish nature because containing it is impossible: “The world breaks every fixed template into which we try to pour it.”

How can we change the ways in which our language abets destruction of nature?

Let’s start by investing more in our relationships with nature — and recognizing the role of language. (One way we wield language is to blanch at the notion that we humans are “animals,” when we’re just as much an animal as the raccoon digging in our garbage.) We can pay more attention to nature. We can stop talking for a moment and listen.

According to Talbot, “If we took the fact of the world’s speech seriously — the world speaks! — there would be none of the usual talk about a mechanistic and deterministic science, about a cold, soulless universe, or about an unavoidable conflict between science and the spirit. Confronting the many voices of nature, we would inquire about their individual qualities and character, we would look for the direction of their expressive striving, and we would struggle to grasp the aesthetic unity of their various utterances — all of which is to say: we would listen for their meanings…. The trouble, however, is that we often fail to pay attention; we never learn the language of the world we inhabit. We try to master nature while becoming increasingly deaf to her complex symphony.”

As Kimmerer notes, in her traditional language, Potawatomi, “There is no it for nature. Living beings are referred to as subjects, never as objects, and personhood is extended to all who breathe and some who don’t. I greet the silent boulder people with the same respect as I do the talkative chickadees.”

She continues, “Beyond the renaming of places, I think the most profound act of linguistic imperialism was the replacement of a language of animacy with one of objectification of nature, which renders the beloved land as lifeless object, the forest as board feet of timber.”

We can create new language. Language is always evolving. (For example, our use of pronouns has recently expanded to recognize those who identify as non-binary and gender neutral.)

It’s our job as global citizens to continually reimagine a better world. We can also undertake the challenge of reimagining new ways to describe the world, using language to craft stories that recognize and honour the myriad living and nonliving entities with which we share the planet.

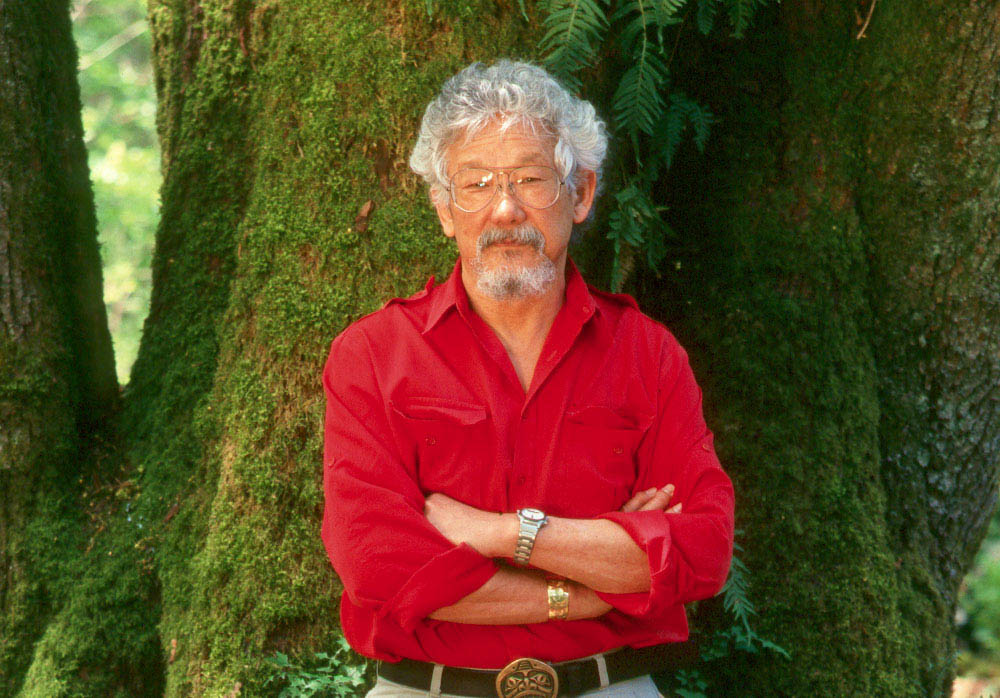

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Boreal Project Manager Rachel Plotkin.