Night diving. Depending on your experience, the two words might either evoke excitement or dread. As the name clearly implies, night diving is diving undertaken during the night… in case you weren’t sure. Diving in itself can feel like a complicated process when you are a beginner, so why would anyone want to make things even more so by diving at night when it’s hard to see? Surely it’s more dangerous too, because marine predators will be stalking you from afar, waiting for you to turn your back and the close in for the kill? What if you lose your buddy, isn’t it so dark that you can’t see anything? These are some of the concerns that someone new to night diving may have, I definitely didn’t feel comfortable about the prospect before my first time doing it. Even the father of all modern diving, Jacques Cousteau, mentions in The Silent World how during his first few night dives, he could not shake the feeling that just outside of his torch beam lurked monstrous shapes ready to devour him whole. The great news is that most people’s preconceptions about night diving are totally wrong, it’s actually a fantastic experience and fear not, I am here to tell you about why it is.

It would be wrong to not first discuss my own original night dive, and the worries I had before heading in. My first night dive was in 2016, on a club summer trip to Tenerife in the Canary Islands. We had already done a good deal of boat diving during the day and the more experienced of the club had decided that it would be a good idea to do a night dive. We had a range of diving experience on the trip with us, some of the less experienced divers (as I was at the time) were a little apprehensive about the idea of getting in the water in the dark. My main concern was that despite me knowing the water was very clear from our days diving (around 25-35m visibility), somehow at night I would not be able to see anything, even with a torch. I had this idea that night time meant visibility was immediately reduced to only a few meters, that only being within my torch beam. There was some element of truth to this concern, but nowhere near to the extent I was imagining. Given the apprehension amongst some of us, we decided that the night dive would begin just after sunset, such that it commenced as a dusk dive, transitioning into total night. Upon rolling in with our torches turned on, it was actually possible to still make out the bottom about 12m below without needing to use the torches. We descended down the anchor line and commenced the dive, and slowly it became totally dark outside of our torch beams. What surprised me was that despite it being pitch black, due to the number of divers in the water with torches, there was a good amount of ambient light. Due to the good visibility, it was easy to locate fellow divers by their torches. For some strange reason, which I still feel to this day on night dives, my buoyancy felt easier to control and everything seems to slow down, maybe due to the fact you are focusing on the area your torch is shining and not much else. If anything, the night dive felt more relaxed than a day dive.

This different feeling you get on a night dive is one of the reasons that I love them. It’s a difficult feeling to describe, but due to the reduced sensory inputs you experience on a night dive, you tend to become more focused on what you can see and control. On a day dive, especially in clear water, it is easy to keep looking around in every direction in an attempt to take it all in. It’s easy to miss some awesome sights if you’re only looking in one direction, but equally being hyperactive will perhaps mean you miss out on some of the smaller things or feel like you can’t afford to stop and take things in if something else swims along. Night diving forces you to only have a cone of light that you can really see anything in, which means that you are much more likely to search this area of light with a keener eye, and perhaps stop to examine things your torch beam does land on. It’s much more of an explorative feeling to day diving, every time you move your beam there’s the potential to find something else new to look at. Had you been diving during the day, you could have just swivelled your head and seen it, but the fact that it was shrouded by darkness adds to the mystery and excitement of what you haven’t come across yet. This exploring by torch beam seems to slow the dives down too, the pace of the dive naturally lends itself to gradually moving your field of vision rather than seeing something distant and beelining for it because it looks interesting. The change in colours on a night dive can also lead to it not really feeling like you are diving. During the day, you can clearly see the distant water fading to blue or green depending on where you are, which makes it feel more like you are underwater. During night dives, where your immediate focus is your torch beam, the loss of colour doesn’t occur so obviously. Distant areas of sea are now just black, the areas in your torch beam are more like their true colours as the light doesn’t pass through enough water to filter down to blue. This seems to trick your day diving brain which is used to seeing things with a blue tint, giving you the feeling that you are floating or flying rather than diving. To me personally, I feel like I could be an astronaut hanging over the surface of a distant planet rather than in the sea. Cave divers describe a similar feeling of flying, I suspect that the colours created by the torch and the lack of ambient sunlight contribute to this. Of course, if you look at a distant source of underwater light, say a buddy pair that are 50m away, then you can see the blue tinge returning, reminding you that you are actually in water.

Night dives also totally change the part of the marine ecosystem you can see practically everywhere. This is particularly obvious in areas with clear water where during the day you might see hundreds if not thousands of fish going about their business. At night, suddenly the residents seem to have gone AWOL, at least it can appear that way when you first begin panning your torch around. Given a few minutes though and you may begin to notice faces peaking out of crevices, distant shimmering of shoals darting out of your beam and moving shadows being cast from the seabed. There is definitely life here… just not as we know it Jim. Ok, well, it is life as we know it, just probably not as you’ve seen during your daylight dives. Notably most of the fish you saw during the day have retired to the comparative safety of their various hidey-holes to rest, but in their place many other different kinds of creatures have emerged. Night dives are a great time to see crustaceans, molluscs, cephalopods and other usual crag dwellers come out into the open. During the day, lots of these creatures would be easy pickings for the resident fish, but at night they come out to feed. During my first few night dives in Tenerife, I was astounded by the sheer number of sea cucumbers, sea slugs and sea hares which were more or less in every direction your turned. There had been no evidence of these in daylight hours, but now that was the sun was down, they had come out in their hordes. On tropical reefs, you can often see parrotfish sleeping in their self-created mucus sacks. You’ll almost always be warned not to shine your light right at them when they’re sleeping, as they can only create this sack once per night and they will be left vulnerable till morning if you startle them and they swim away. Crustaceans such as spiny lobster which are typically hiding deep under rocks or coral are also trundling around in search of scraps. There’s often much more to see going on at or near the sea bed on a night dive than in the midwater, though that isn’t to say that you don’t see anything higher in the water column. Squid which spend most of their time hidden in much deeper water sometimes make an appearance on night dives, often in groups. You may even be lucky enough to see some hunting behaviour of predators such as moray eels, depending on where you’re diving, which systematically move through the reef searching for unaware prey.

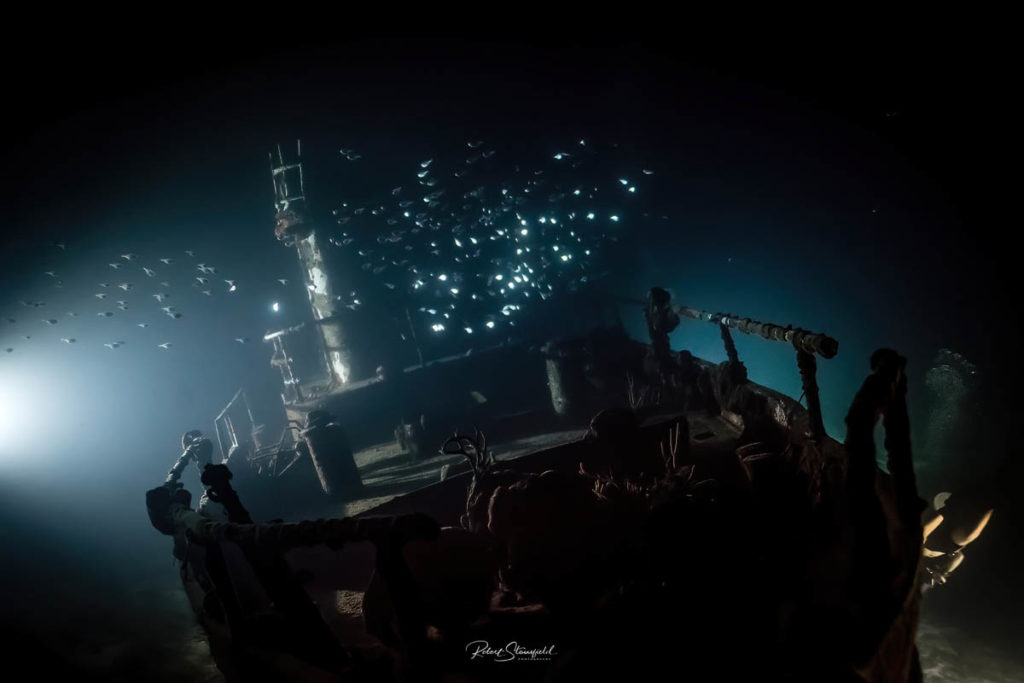

A site can look so different on a night dive that it feels like you are somewhere else entirely. This means that if you were to treat every sight you dived as both a day and night dive option, you essentially get two totally different dives in the same location. One of the most notable night dives I ever did was in the Red Sea in 2019, on the SS Thistlegorm. The Thistlegorm is an incredibly impressive wreck in itself and a standalone cracking dive regardless. For those that are unfamiliar with her, she is a British cargo ship that was sunk in Safe Anchorage F near the Gulf of Suez during the second world war. She is 128m from bow to stern, and sits on the seabed in around 30m of water. It is such a large wreck that it often takes three or four dives to explore every part of her, and there are multiple different routes for penetrating the cavernous interior. At night it is dangerous to dive the interior, so my buddy and I planned to carry out a dive on her upper foredecks before dropping off the bow to the seabed and diving back along her port side to see if anything was on the sand. The visibility had been unremarkable during the day, about 20m and cloudy due to choppy surface conditions. At night our torch beams only reached about 8m through the water. Following the rope from our liveaboard to the wreck, it took an eternity for any hint of the structure to appear out of the murk. Once on the wreck, we began exploring towards the bow, jumping out of our skin occasionally when large batfish would loom out from behind the wreck and right into our beam only to spook and bolt away. There were also some incredibly large Lionfish which followed our torch beams, waiting for the opportunity to snatch any smaller fish they illuminated. Reaching the bow, I stuck my head over and shone my torch over the gunwales towards the seabed. I knew it was about 15m below me, but the torch found nothing but cloudy black. I signalled to my buddy that this was where we were going to swim off the edge, and over we went. I’m not sure if the seabed had been relocated or we were just exceedingly slow on our descent, but the bow of the ship didn’t seem to end. It was like swimming down a metal wall into the abyss. Finally, we reached the seabed, where the visibility was even lower than on the wreck above. It was the first time I felt really uncomfortable on a dive, I was paranoid that we were about to get swallowed up by the darkness. We swam about 8 meters down her portside where she rested on the sand, before deciding to ascend back to the deck again. It then took us a long while to find our bearings relative to where we had actually descended onto the wreck. Maybe it was the fact she is a war grave, nine of her crew perished during the sinking, or perhaps it was just the visibility, but we were glad to get back on our boat at the end. Almost all of the experience was simply because we had dived her at night, creating a totally different kind of atmosphere and limiting our visual information.

Night diving is overall an excellent experience, something I feel allows you to really get to know an area intimately. How can you know a site well if you have only seen it during one set of lighting? Of course, some sights may not be safe or sensible to dive at night, but when presented with the opportunity to dive at night, it is a unique and invaluable experience. For those of us that do plenty of diving in daylight hours, it’s the perfect way to change up the pace and the technique in order to keep things feeling fresh. It has the added benefit of letting you see some totally different wildlife, as well as the opportunity to get a different perspective or feeling to a dive site you might otherwise be familiar with. Nowadays, I leap at the opportunity to go night diving. Just don’t forget to bring a backup light.