During their miraculous but perilous journey from inland spawning grounds, down rivers, out to sea and back again years later, Pacific wild salmon often must pass open-net coastal salmon farms. Here they swim through waters that can harbour parasitic sea lice and harmful viruses and bacteria.

In its 2012 report, the Cohen Commission of Inquiry into the Decline of Sockeye Salmon in the Fraser River identified potential dangers to salmon migrating through the Discovery Islands between B.C.’s mainland and Vancouver Island. In response, the provincial government put a moratorium on new fish farm tenures in 2013. It was set to expire September 30, but B.C.’s snap election puts salmon farm policy in question.

September 30 was also the Cohen Commission’s deadline to remove the 18 existing Discovery Islands fish farms unless government could show they pose no more than “minimal risk of serious harm” to wild Fraser sockeye.

These farms have continually failed to meet the “minimal risk” threshold. The aquaculture industry’s own data show 33 per cent of farms exceeded the sea lice limit while juvenile salmon were migrating past this year.

A Fisheries and Oceans Canada review failed to consider sea lice impacts or the cumulative effects of the nine pathogens it assessed. Although seven of the nine risk assessments showed some degree of uncertainty (with two showing high levels), the review concluded the farms pose no more than minimal risk and can stay.

Ignoring the pathogens’ cumulative impacts provides an incomplete view. Not including sea lice risks defies logic.

Biologists and First Nations submitted evidence showing lice continue to harm wild salmon, despite control efforts. Those controls rely on chemicals that can harm the environment, and lice are becoming resistant to them. A consortium of 101 First Nations, along with sport fishing groups and ecotourism operators, demanded the farms’ removal.

Sea lice that target wild salmon occur naturally but weren’t a problem before fish farms. In the ocean, fish can survive with a few lice attached. They fall off when the salmon return to freshwater. But sea lice thrive where thousands of salmon are penned in one place. They often attack a salmon’s head and neck and eat its skin, eventually killing it. They’re especially dangerous to juveniles migrating from freshwater to the ocean.

Because salmon spend their lives inland and at sea, they beautifully illustrate the connections between ocean, freshwater and terrestrial ecology. They bring nitrogen from oceans to streams and rivers, where eagles, bears and other wildlife that feed on them spread it throughout the rainforests, providing nutrients that keep the forests strong. They are also integral to First Nations cultures and diets.

When wild salmon disappear, ecosystems and ways of life collapse.

Besides sea lice and pathogens like Piscine orthoreovirus, farmed Atlantic salmon escapes can threaten wild salmon populations. In 2017, a pen in Washington state owned by Canadian company Cooke Aquaculture broke open, releasing 300,000 Atlantic salmon into the Pacific and nearby waterways. Some were caught and it appears most eventually died and didn’t mix with wild salmon, as they would have on the Atlantic coast. But the incident convinced the state to phase out salmon farms by 2025. Oregon, California and Alaska have banned them.

We should do the same. This year’s Fraser River sockeye salmon runs have been the lowest on record. To justify its continued existence in this sensitive environment, the aquaculture industry is sowing confusion around the uncertainty of evidence, but that doubt should inspire a precautionary approach.

Feeding a growing human population is a challenge. We can’t continue plundering the seas and exhausting them of wild fish. But we must ensure that aquaculture is done in ways that don’t harm the environment. For fish farms, that likely means moving them to closed systems on land, which cost more, and growing less ecologically damaging species, like shellfish, which can have a lower profit margin.

Short-term profits for big companies aren’t worth risking entire coastal ecosystems and ways of life. Amid the current climate and biodiversity crises, people must demand changes so food production meets human needs without destroying the natural world that feeds us.

Let’s at the least get fish farms out of the way of migrating wild salmon. That means removing them from the Discovery Islands now.

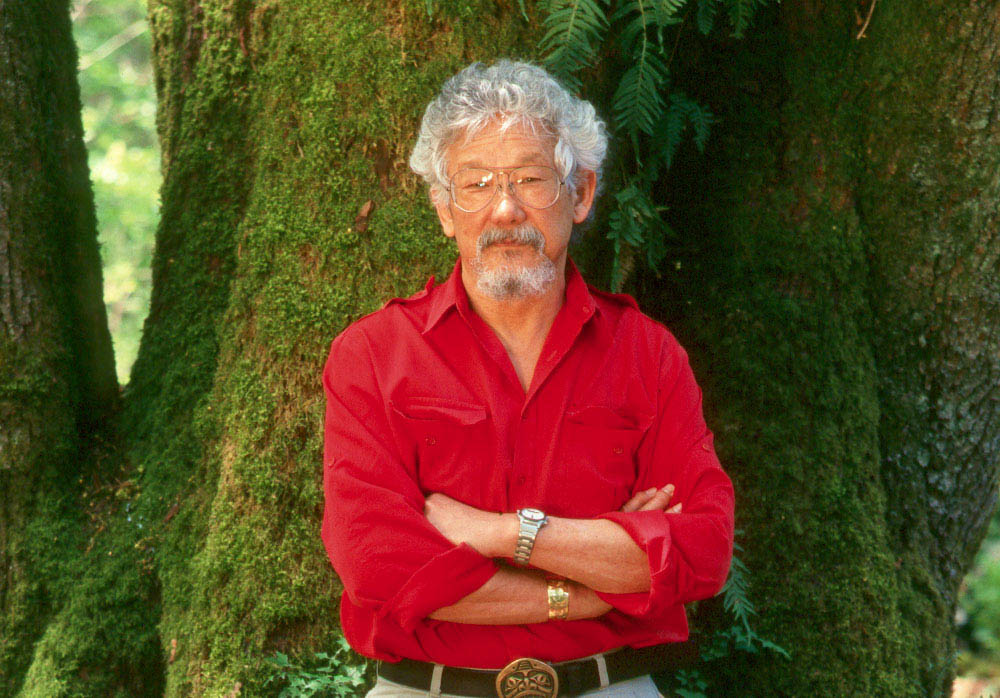

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Senior Writer and Editor Ian Hanington.