On 25 October 1918, after grounding on Vanderbilt Reef in the Lynn Canal near Juneau, Alaska Territory, SS Princess Sophia sunk with the loss of all aboard. All 364 people on the ship died, making the wreck of Princess Sophia the worst maritime disaster in the history of British Columbia and Alaska.

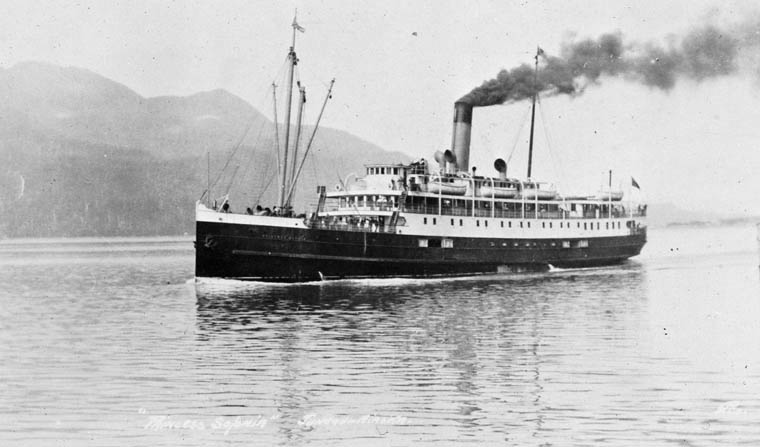

A steel-built passenger liner in the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) coastal service fleet was the SS Princess Sophia, along with SS Princess Adelaide, SS Princess Alice, and SS Princess Mary, was one of four similar ships constructed during 1910-1911 for the CPR. Princess Sophia was a 2,320 Gross Register Tons (GRT) and 1,466 Net Register Tons (NRT) steamship constructed at Paisley in Scotland. She was made of steel with a double hull, a solid, sturdy vessel. As its use on the stormy west coast of Vancouver Island showed, Princess Sophia was able to handle more than just the “Inside Passage”. Princess Sophia originally burned coal, but soon after her arrival in British Columbia, the vessel was converted to oil fuel.

Princess Sophia was described as very comfortable, particularly in first class. She had a maple-panelled forward viewing lounge, a social hall for first-class passengers with a piano, and a 112-seat dining room with wide windows to view the coastal landscape, and was fitted with wireless communications and full electric lighting.

In addition to transporting travellers, Princess Sophia ran a much-needed service from British Columbia to Alaska. The route from Victoria and Vancouver, British Columbia ran through the winding channels and fjords along the coast, stopping for travellers, freight, and mail in the main towns. Today, this path is still relevant and is called the “Inside Passage”. Prince Rupert and Warning Bay, British Columbia, Wrangell, Ketchikan, Juneau, and Juneau are major ports of call along the “Inside Passage”.

Princess Sophia departed Skagway, Alaska, at 10:10 pm on 23 October 1918, more than three hours behind schedule. The next day, she was scheduled to stop at Juneau and Wrangell, Alaska; on October 25, Ketchikan, Alaska, and Prince Rupert; on October 26, Warning Bay, British Columbia; and on October 27, Vancouver. There were 75 crew and about 268 passengers on board, including families of men fighting in the war overseas, miners, and crews of sternwheelers that had ended winter operations. Fifty women and children, including the wife and children of gold speculator John Beaton, were on the passenger list. The steamship encountered heavy blinding snow propelled by a strong and rising northwest wind four hours after leaving Skagway, while continuing south down the Lynn Canal.

According to David Leverton, the executive director of the Maritime Museum of British Columbia, Captain Locke navigated the Lynn Canal at full tilt, probably in an effort to make up time. He added that the weather included heavy snowfall, so the crew was forced to use dead reckoning by blowing the whistle of the ship and measuring its position inside the canal, based on the time it took to return the echo of the whistle. He estimated the ship was off course at least one nautical mile (1.9 km; 1.2 mi). At 02:00 am on 24 October 1918, Princess Sophia struck the ground hard on Vanderbilt Reef, 54 miles (87 km) south of Skagway, Alaska and a distress message was immediately sent.

David Leverton of The Maritime Museum of British Columbia says::

“By the time they actually reached the vicinity of Vanderbilt Reef, it was just shortly after 2 a.m. in the morning, so it was pitch black,” Leverton told CBC News. “They were in a blinding snowstorm, heavy seas”. At the time, Vanderbilt Reef was at extreme high tide and was unlit. “There’s no way they could have seen it,” Leverton concluded.

Princess Sophia was encircled on both sides by the exposed rock at low tide. At high tide, the rock was overflowing, but the swells were such that when the waves pounded up and down, lifeboats if launched, would hit the rocks. Without life-threatening risk, the passengers could not be rescued from the vessel. Due to the fact the Sophia was caught between two sets of rocks, with rough seas and blustery winter conditions, the only way she could be removed from the reef would be with the help of 2-3 tugs.

The Cedars Captain Ledbetter had a wireless rescue ship and was thus able to stay in close touch with Princess Sophia, to coordinate the rescue operation. While risky, and maybe even desperate, the rescue strategy was to wait until the next day at high tide when the reef was at a few feet of water. It was hoped that this would be sufficient to launch Sophia’s boats and use them to carry the people to the rescue ships from Princess Sophia. The Cedars with Captain Ledbetter stayed anchored nearby the SS Sophia for the night.

David Leverton of the British Columbia Maritime Museum told the CBC that a change in the weather was forecast by the captain’s barometer and recommended to rescuers that they try the next day.

“They had seven different rescue ships ready to come to the aid of the ship if it foundered off the reef. But what ended up happening was that it settled down on the reef” until approximately 5 p.m., when it was lifted off the reef.

What happened to Princess Sophia to force her out of the reef, without survivors and no witnesses to the actual sinking, is a matter of reconstruction from the available facts and speculation. Based on the data, the wind, blowing from the north, seems to have raised water levels on the reef far higher than before, causing the vessel to become buoyant again, but only partly so. The vessel’s bow stayed on the reef, and the wind and wave action then turned the vessel almost entirely around and washed it off the reef. Dragging across the rock, the ship’s bottom ripped out, so she sunk when she entered deeper water near the navigation buoy. This process seemed to have taken about an hour, based on the facts.

No time for a co-ordinated evacuation appears to have been issued. Many passengers carried lifejackets and there were two wooden lifeboats (the eight steel lifeboats sank) floating away. When the ship sank, there were about 100 people left in their cabins. It’s hard to know why, if it took an hour for a ship to sink, there were so many people under the decks, but there might be a lot of explanations. The boiler could have exploded as seawater entered the ship, buckling the deck and killing several passengers. Fuel from oil leaked into the sea, choking people who were trying to swim away. Sophia had been fitted with additional flotation devices, on the premise that in the water waiting for help, people could cling to them. These were useless, since long before help could come, with the cold seawater, hypothermia would set in quickly.

It was still snowing the next morning, 26 October, but the wind had died down a little. Returning to the reef were the King, Winge and other rescue boats. Just Princess Sophia’s foremast remained above water. For three hours, the search boats cruised around searching for survivors. Bodies were identified, but no humans survived. A small dog, presumed to belong to a wealthy couple on board, was the only survivor who was able to swim to a nearby island and was rescued a few days later at Auke Bay, outside Juneau, Alaska.

Read The Scuba News Canada’s Article about Unsolved Mystery of the Sinking of the SS Princess Sophia

The bodies were taken by the King and Winge to Juneau. Cedar returned to Juneau as well. Captain Ledbetter (Cedar) sent out a wire when he arrived, stating:

“No sign of life. No hope of survivors.”

The bodies were washed up for months after the wreck, up to thirty miles north and south of Vanderbilt Reef. Wreckage and the belongings of the passengers, including toys from the children who had died on the ship, were also found. Many of the skeletons, coated with a thick layer of oil, were barely identifiable as human remains. Most of the recovered bodies were brought to Juneau, where several local residents volunteered to assist in identifying the remains and preparing them for burial. For the oil to be removed, the corpses had to be scrubbed with gasoline. The women’s teams prepared the female bodies, while the men’s teams managed the males. The volunteers were especially impacted by the children’s bodies. Divers retrieved about 100 bodies at the wreck site. Months after the wreck, several were found floating in cabins.

Many people felt that Captain Locke’s decision not to evacuate the ship was a significant mistake and that most or even all of the passengers should have been saved. After hearing testimony from first-hand witnesses, the Ministry of Marine reached a similar conclusion in 1919. After the courts decided that the decision was within the fair range of the Captain’s judgement, right or wrong. Cedar’s Captain Ledbetter claimed that he never saw circumstances, in his opinion, that would cause the ship to be rescued, but he was cautious, almost 50 years later, to state that this was as much as he could say from when he arrived at the reef, which was October 24.

The families of passengers brought legal action against The Canadian Pacific, but these failed.

Sometimes called “Canada’s Titanic” Canadian Pacific Steamships’ coastal liner SS Princess Sophia has been compared to the Titanic because of the appalling loss of life, 343 men, women and children.