One caribou herd in Jasper National Park is gone. The two remaining are on the brink. Regrettably, the story is not particularly new; almost every caribou herd in Canada has been assessed as being at risk of extinction, and too little is being done to save them.

Last year in British Columbia, two caribou herds — the South Selkirk and South Purcell — died out. Caribou along Lake Superior’s north shore are clinging to survival, dislocated from their relatives further north by extensive habitat fragmentation that requires aggressive restoration. Even though Jasper National Park is a protected area, past poor wildlife and access management and disturbed surrounding landscapes have made survival difficult for caribou there. Backcountry trails and lodgings are still open from mid-February to mid-October in high-quality caribou habitat of one of the remaining herds.

What do we lose when a population or species becomes extirpated; that is, locally extinct?

Most scientists would argue there’s no absolute answer. Nature is too complex and species too interdependent for us to comprehend how the loss of a particular plant or animal species will affect the ecosystems of which it is a part.

Species extinguishment is not merely an ecological loss, though. Many people are grieving the vast biodiversity decline the planet is facing. It’s now widely accepted that exposure to nature is good for mental health, but the opposite is also true. When we turn away from the wondrous world not shaped by human hands and decrease our connection to other living things, we can be struck by profound loneliness. Indeed, pre-COVID, many social scientists described loneliness as an emergent pandemic. Recent studies show that one in five people in Canada identifies as lonely.

In Our Wild Calling: How Connecting with Animals Can Transform Our Lives — and Save Theirs, author Richard Louv writes, “While green spaces can bring joy and reduce stress, a deep connection to other animals has a special power to deliver us from our isolation, both as individuals and as a species.”

A sense of bereavement was clear in media interviews following B.C. caribou extirpations. Local hog farmer Jim Ross told the Narwhal, “It just saddens the hell out of me. I have two daughters who are 19 and 21 and they’re never going to see a caribou. It’s just not going to happen for them unless they see it in an enclosure.”

Wildlife biologist Leo DeGroot echoed that sentiment: “It’s sad to see these animals go. It’s such an iconic animal. They’ve been on this landscape for thousands and thousands of years. Due to human influences largely, they’re gone now.”

The loss of caribou herds is deeply felt by many Indigenous Peoples whose ways of life and sustenance have been connected to caribou for millennia. When the caribou they have lived in relation with for generations no longer show up for seasonal rounds, many people have articulated an intense loneliness. Elders from Doig River and West Moberly First Nations have expressed a longing to eat caribou once again before they die.

Chief Patricia Tangie of the Michipicoten First Nation in Ontario has fought hard for the survival of caribou on Lake Superior’s shores. When they were almost wiped out in 2017, she led efforts for a relocation initiative. As Michipicoten lands and resources consultation co-ordinator Leo Lepiano said, “We’ve arrived at a time when the rest of the animals on the planet need our help to survive. These are animals that have helped the Ojibwe people survive in the past.”

Unwillingness to change the status quo is the biggest barrier to caribou recovery. Extirpation can also turn into a perverse incentive for industrial and commercial operations that degrade critical habitat. Once caribou are gone, so too are requirements to protect and restore their habitat.

Caribou, like most species, can be bred in captivity, and populations can be augmented, but there is little value in doing so without adequate habitat to support their life cycles. Significant efforts are needed to restore habitat where it has been lost.

We must cherish our present relationships with nature and hold space for future connection by fighting for wildlife survival. One way to do this is to support recovery measures, including maintaining and restoring habitat, for highly imperilled caribou populations — before it’s too late.

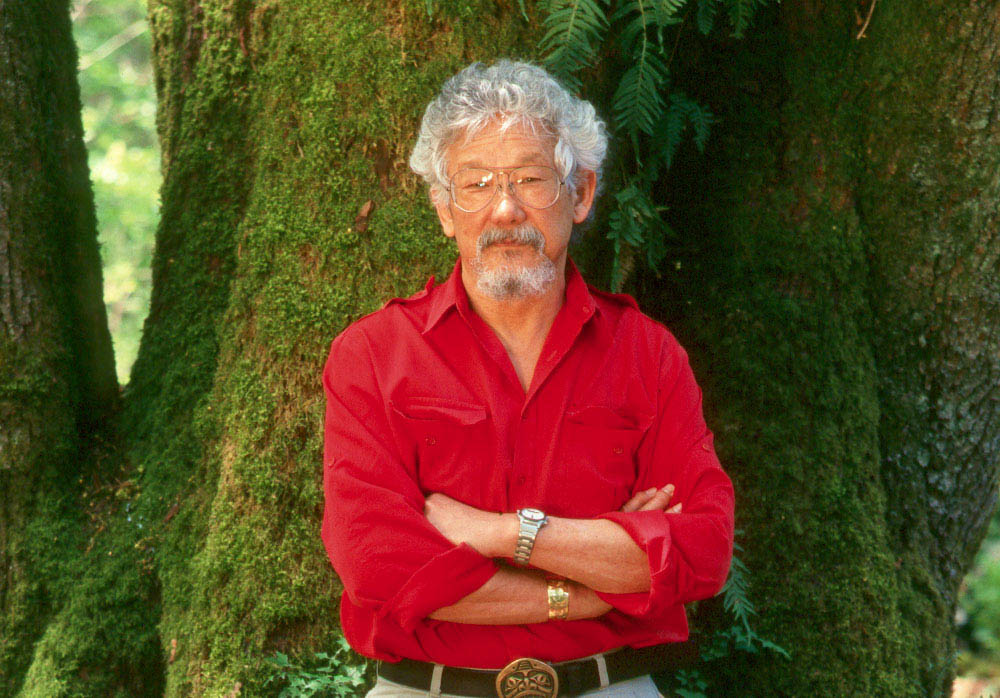

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Boreal Project Manager Rachel Plotkin.