What we refer to as “plastic” hasn’t been around for long. But its usefulness has caused production to skyrocket — from about two million tonnes in 1950 to almost 400 million tonnes a year now, and rising steadily. It’s a problem.

Although much of it can be recycled, most isn’t. That’s led many local and national governments worldwide to ban or consider bans on non-essential “single-use” plastics. Canada plans to prohibit many items by the end of 2021, but the list isn’t comprehensive. Plastic grocery bags, cutlery, straws and stir sticks, beverage-pack rings and a few more items will be prohibited. Garbage bags, snack-food wrappers and beverage containers won’t.

The exemption for beverage containers, in particular, is controversial. Many argue they’re unnecessary and are petitioning government to include them. Others note that bottled water is sometimes needed in emergency situations. And some communities, especially Indigenous communities, still lack access to safe tap water.

The federal government, which is accepting public input on the issue until December 9, says beverage containers won’t be included in the proposal for the ban’s “first wave” because they’re easy to recover and recycle and are necessary in communities that don’t have access to clean water. It’s proposing recycled content requirements for plastics not subject to the ban, but the focus ought to be on reducing plastic packaging in the first place.

We note that the government committed to ending long-term boil-water advisories on First Nations by March 2021, but the pandemic has put that deadline in question. As for recycling, of the 5.3 million bottles of water Canadians buy each day, more than 90 per cent end up in the environment, as do the enormous quantities of other plastic-bottled beverages.

Recycling requires a lot of energy, and plastic polymers break down in the recycling process. That, along with low fossil fuel prices, makes new oil-derived materials more cost-effective than recycled plastic. But it takes more water to create a plastic bottle than the bottle will hold, and the energy required to produce a bottle of water is 2,000 times that to produce the same amount of tap water.

The government says it wants to work with provinces to ensure more plastics are recycled, but it will be challenging.

Although many concerns around banning single-use plastic beverage containers are valid, ban proponents argue they aren’t insurmountable — and the reasons to include them in a ban are compelling. To start, alternatives based on “reduce and reuse” distribution are available and could be expanded. Most people in Canada have access to safe tap water, even though 20 per cent continue to drink water from bottles. Some beverage companies already offer the option to refill reusable containers, which will be part of the solution. Furthermore, even in the realm of single-use packaging, aluminium and glass are easier to recycle than plastic, as they don’t degrade in the same way as plastic during the recycling process.

But we must prioritize “reduce and reuse” if we’re going to make progress toward zero waste. The truth is we don’t need most of the sweetened beverages sold in single-use plastics, and our bodies might be better off without them! Water is an exception. But Canada has the infrastructure to provide high-quality tap water to most communities, at a much lower cost than bottled water. Tap water is also far more regulated and tested than bottled water, which can contain microplastics and other contamination. In fact, most bottled water is obtained from municipal or public water supplies, at little or no cost to corporations like Coca-Cola, PepsiCo and Nestlé.

Studies also show that people ingest the equivalent of a plastic credit card every week. And the impacts of plastic pollution on oceans are a major threat to marine life and to human health and survival — not unlike the impacts of fossil fuels, from which plastics are made.

At the very least, all single-portion plastic beverage containers should be banned and no effort should be spared to ensure everyone in Canada has access to safe tap water. Canada is fortunate to have plentiful water and the capacity and knowledge to deliver it to people.

Beverage containers are among the most ubiquitous of environmentally devastating plastics. We don’t need single-serve plastic bottles.

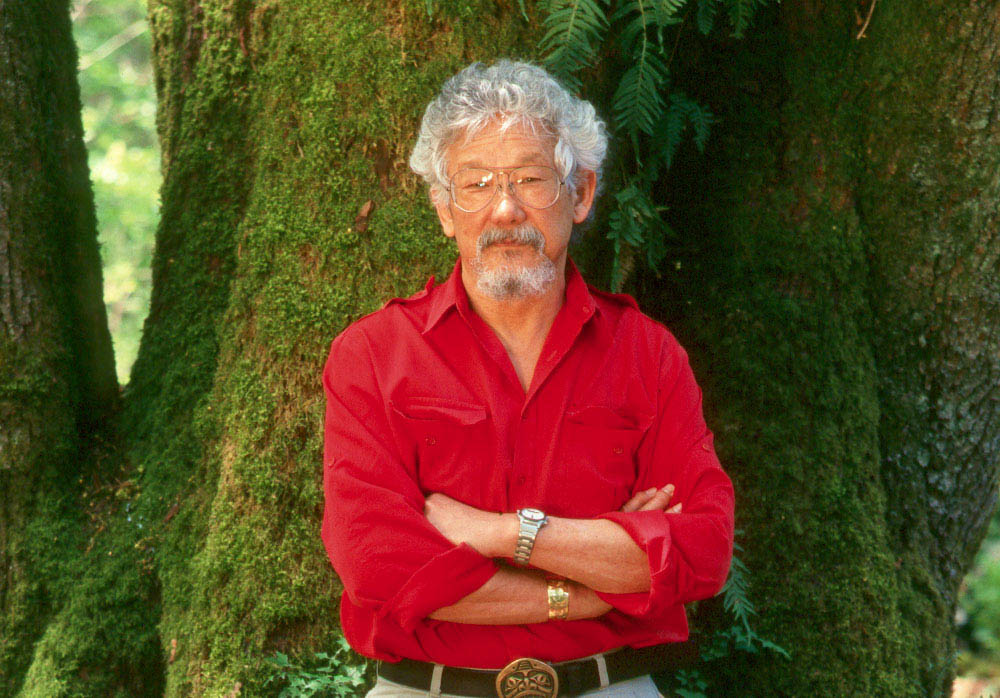

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Senior Writer and Editor Ian Hanington.