One of the more recent shipwrecks, the Cutter Mesquite hit on a reef in 1989 near the Keweenaw Peninsula in Lake Superior. No lives were lost. She now rests in 120 feet of water on the Keweenaw Peninsula and is a popular dive due to the fact that most of the equipment is still on its deck.

The Keweenaw Peninsula is the northernmost portion of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. It was the site of the first copper boom in the United States and the home of 12 official wrecks. It projects into Lake Superior and has been called the “catcher’s mitt” of lost ships.

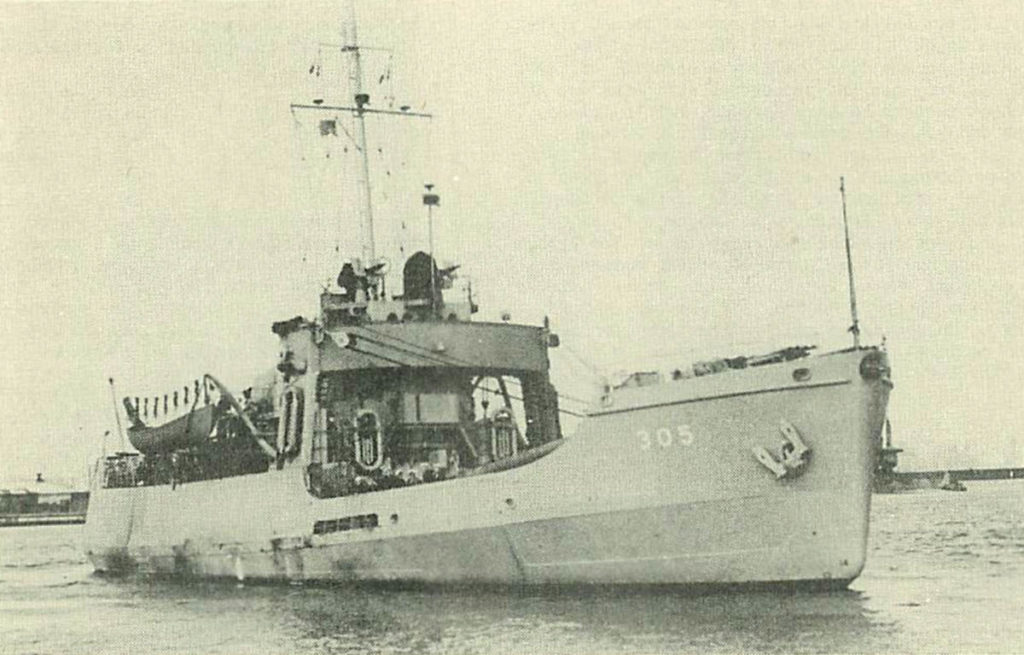

The Mesquite was constructed at a cost of $874,798 at the Marine Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company yard in Duluth, Minnesota and launched on November 14, 1942. She was built for light ice-breaking performances. Her hull was strengthened along her waterline with an “ice belt” of thicker steel to shield it from ice punctures. Similarly, her bow was strengthened and shaped to travel over ice. Her first brief assignment was to the 5th District of the Coast Guard, which was in charge of the mid-Atlantic coast. She was scheduled for service in the Pacific within a month and began a series of preparatory training exercises. On February 29, 1944, Mesquite sailed through the Panama Canal to reach Brisbane, Australia. On April 16, 1944, she reached Milne Bay in New Guinea.

Mesquite’s first home port was Sault Ste Marie, Michigan, after returning from the Pacific, where she arrived on December 5, 1947. Her primary mission was to maintain navigational aids. The annual advance and retreat of heavy winter ice on the Great Lakes was the catalyst of most of her action. In the fall, buoys were brought to port to prevent them from being destroyed by ice, sunk, or set adrift. Over the winter, the buoys were washed, repaired, and repainted and redeployed by the vessel in the spring.

Icebreaking, a service she conducted during her career, was her second job. Freeing ships that were frozen in the ice was one part of her icebreaking work. The tankers Edward G. Seubert and Clark Milwaukee were frozen-in on their way to Green Bay, in April 1960. She also participated in numerous search and rescue missions.

Mesquite began her regular duties by picking up her buoys before they could be hit by advancing ice. USCGC Sundew came out of shipyard repairs late, so Mesquite was tasked with removing some of her buoys as well. Mesquite picked up 25 of her own buoys and went to pick up Sundew’s from Lake Superior. Before pulling the light buoy marking the shoal off Keweenaw Point, she collected at least 35. With the buoys aboard, Mesquite got underway. At approximately 2:10 am on December 4, 1989, she ran onto the shoal and went aground. The hull was pierced, but the pumps were able to keep pace with the incoming water. Wind and waves were moderate, but enough to pound the ship on the rock. The flooding became uncontrollable after three hours. At 6:17 am the captain ordered Mesquite to be abandoned, and the crew was safely evacuated. A passing cargo vessel, Mangal Desai, responded to Mesquite’s distress call and took the crew on board.

On December 8 and 9, strong winds and waves of up to 10 feet hit the grounded Mesquite, further damaging the hull, breaking off her rudder, and overturning her mast. At this point, the Coast Guard concluded that the ship could not be salvaged in the winter conditions.

After it was removed from the shoal, there were three alternatives considered for the Mesquite. It could be scrapped or second, it could be repaired and returned to service, but this option was quickly rejected at an estimated $44 million cost. Third, not far from its grounding, it could be scuttled and become a recreational diving attraction.

Scuttled was decided and the Mesquite was stripped of useful parts in preparation for her descent to the bottom of Lake Superior, including the propeller, cargo boom, and anchor windlass that the Coast Guard needed for its stores. A lot of loose material has been hauled off and much of the structure was hacked out. The residual gasoline, tar, paint and other harmful materials were removed as well. To minimize the wreck’s weight, flooded compartments of the ship were either pumped out or blown out with compressed air. On July 14, 1990, Mesquite was eventually lifted off its ledge and lowered to her final resting place in Lake Superior.

After the grounding, the Captain of Mesquite preferred to stand for a court-martial rather than resign. He was found guilty of risking his vessel in September 1990 but was cleared of dereliction of duty. The appeal of his conviction was dismissed in January 1991.

This is a 120-foot dive in Lake Superior and recommended only for cold water/experienced divers.