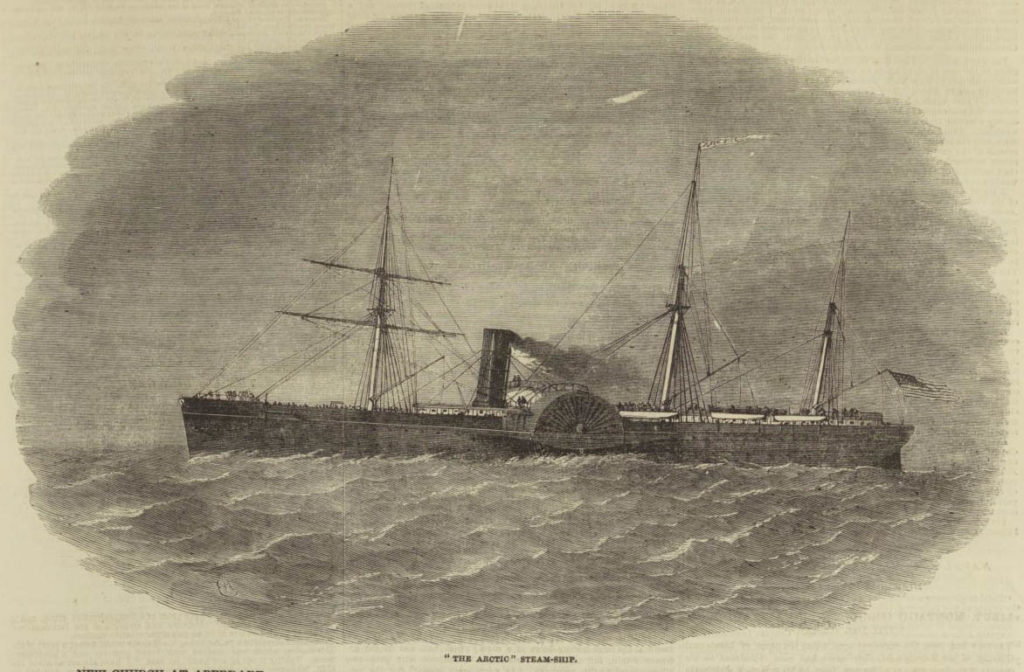

The SS Arctic was a 2,856-ton paddle steamer that served as part of the Collins Line’s transatlantic passenger and mail service in the 1850s. She was the largest of a fleet of four ships constructed with US government subsidies to counter the British-backed Cunard Line’s transatlantic dominance.

The ship was known for its speed as well as the elegance of its accommodations during its four-year service. Arctic was released in front of a huge crowd on January 28, 1850, from Brown’s yard on the East River in New York. She was “the most stupendous vessel ever built in the United States, or the universe, since the patriarchal days of Noah,” according to a press report.

Arctic earned a reputation as one of the world’s fastest ocean liners, routinely completing the journey in ten days or less; in February 1852, she arrived in Liverpool in nine days and seventeen hours, a record time for a winter crossing. She was dubbed the “clipper of the sea” and became the most popular of the Collins ships.

Before her fatal voyage, the SS Arctic had two disasters, she ran aground on the Burbo Bank in Liverpool Bay while on a voyage from New York to Liverpool in November 1853. She was refloated and brought back to Liverpool. On a voyage from Liverpool to New York in May 1854, the Arctic collided with the Black Rock off the coast of the Saltee Islands in County Wexford. Again, she was returned to Liverpool after being refloated. Arctic’s engines were modified in July 1854 in the hopes of lowering the ship’s high fuel costs, which were threatening its profitability.

The Disaster

The Arctic collided with the SS Vesta, a much smaller vessel, 50 miles off the coast of Newfoundland on September 27, 1854, while en route to New York from Liverpool. On board the Arctic, there were about 400 people: 250 passengers and 150 crew members. The Captain, Luce’s first thought was to help the stranded Vesta, which seemed to be sinking, but when he learned that his own ship was holed beneath the waterline, he headed for shore. Arctic’s hull slowly filled with sea water as efforts to plug the leaks failed. The boiler fires died out steadily, and the engines slowed and came to a halt, still far from shore.

Arctic was equipped with six lifeboats, each with a capacity of about 180 people, in compliance with the maritime regulations in effect at the time. Captain Luce ordered these to be launched, but due to a breakdown of crew control, the majority of the seats in the boats were taken by crew members or the more able-bodied passengers. The principle of “women and children first” was ignored. Makeshift rafts were used by some of the passengers, but most of them went down with the ship. 24 male passengers and 61 crew members were among the 400 people on board that survived.

Two of the six lifeboats that left Arctic arrived safely on the Newfoundland coast, and another was picked up by a passing steamer that also rescued a few survivors from makeshift rafts. Captain Luce was one of them, having resurfaced after initially sinking with the ship. After two days of clinging to the wreckage of the paddle-wheel box, he was rescued.

Meanwhile, the SS Vesta, which appeared to be in grave danger, was rescued from sinking by her watertight bulkheads and was able to reach St. Johns, Newfoundland.

Aftermath

Because of the limited telegraph communications available at the time, news of the sinking of the Arctic did not reach New York until two weeks later. When the full story emerged, initial public grief over the ship’s loss soon gave way to criticism of the crew’s alleged cowardice and inability to serve their passengers. Despite the demands of some newspapers for an investigation into the tragedy, none was held, and no one was held accountable for their actions. Lifeboat space on passenger-carrying vessels should be expanded to provide a position for all on board, but proposals to do so were not acted upon. Captain Luce retired from the sea after the public absolved him of blame; some of the crew survivors decided not to return to the United States. The Collins Line operated a transatlantic service until 1858, when it was forced to close due to further maritime losses and insolvency.

As a result, in December of that year, the United States agreed to contribute to the construction of a lighthouse at Cape Race, Newfoundland. Furthermore, ship routing was planned to prevent accidents by setting up routes on both the East and West Trans-Atlantic routes.

The Collins Line’s president, James Brown, erected a grand memorial to the six members of his family who died in the tragedy in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. A sculpture of the ship, half-submerged by the waves, is included. On the pedestal are engraved the names of those who perished.