Considering the language G7 leaders used going into their mid-June summit in Cornwall, U.K., it’s difficult not to be disappointed with the outcome. In what appeared to be a sign they were finally realizing the seriousness of the climate and biodiversity crises, including economic consequences, leaders of the world’s seven leading economies were echoing the words of the environmental movement.

Politicians from Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the U.K. and the U.S. talked about the need to “build back better” from the pandemic and create a “greener, more prosperous future” by protecting the planet, safeguarding people’s health and building global resilience against future pandemics, and championing shared values including democracy and human rights, among others.

U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson even called for a climate “Marshall Plan” — referring to America’s massive rebuilding efforts in Europe after the Second World War — under which the richest economies would provide funds to help developing nations drastically cut carbon emissions.

But what the leaders settled on is underwhelming, and some just reaffirms previous commitments. They agreed to cut collective emissions in half by 2030, stem the extinction crisis, end funding for coal projects that don’t have a way to capture and store carbon, decarbonize the electricity sector and create a fund to help countries transition from coal. They also agreed to conserve or protect 30 per cent of their countries’ land and marine areas by 2030.

But despite calls from the U.K., they failed to specify a deadline for halting coal-fired electricity, instead issuing a vague statement that they would “rapidly scale up technologies and policies that further accelerate the transition away” from coal that doesn’t use carbon capture technology.

Some say the G7’s weak position on coal will hurt efforts to encourage China to scale back on coal power expansion at the November climate summit in Glasgow. Critics have also argued funding is inadequate for countries that had the least to do with causing the climate crisis but are suffering the most.

Will increased attention to climate and biodiversity at least spur the G7 countries to up their climate targets and ambitions? It’s hard to say — the G7 has been pledging to end fossil fuel subsidies since 2009, and those continue.

Let’s hope members and all world leaders start to adopt rather than co-opt the environmental movement’s language and take the commitment to “build back better” seriously.

Global efforts to resolve the climate and biodiversity crises fall far short of what’s needed from all countries, especially wealthy nations that have contributed most to the problems. But growing recognition of the absolute urgency appears to be finally hitting home as decades of stalling have turned what could have been an opportunity into an emergency.

COVID-19 has opened a window onto the systemic failures that lead to ecological and health crises, and inequalities, but it’s also shown that countries that rely on science and co-operation can accomplish a lot by mobilizing resources. With rapid advances in energy efficiency and renewable energy and storage, there’s no reason we can’t marshal what’s needed to address the climate crisis.

We’ve resisted change for so long, though, that significant progress must now come from the top. As good as individual actions are — from driving less and conserving more to eating less meat and turning down the heat — the best action we can take is to put pressure on governments and industry to confront the ecological crises with resolve and determination.

That can mean calling or writing your elected representatives, joining climate marches or simply making informed voting choices. It often takes growing public pressure to wake politicians from their conventional short-term, election-cycle thinking and priorities.

We’re already bringing about significant change. The Keystone XL pipeline is cancelled, shareholders have voted to make oil companies more responsible for their contributions to climate disruption, people are divesting from fossil fuels, a conservative government in the U.K. has called for a climate “Marshall Plan” — all largely because of the tireless efforts of committed citizens and activists.

The COVID crisis has roused many to the urgency of the related ecological crises — including politicians, financial leaders, shareholders and CEOs. They’ve spoken up; now we must hold them accountable to their words and push them to do even more.

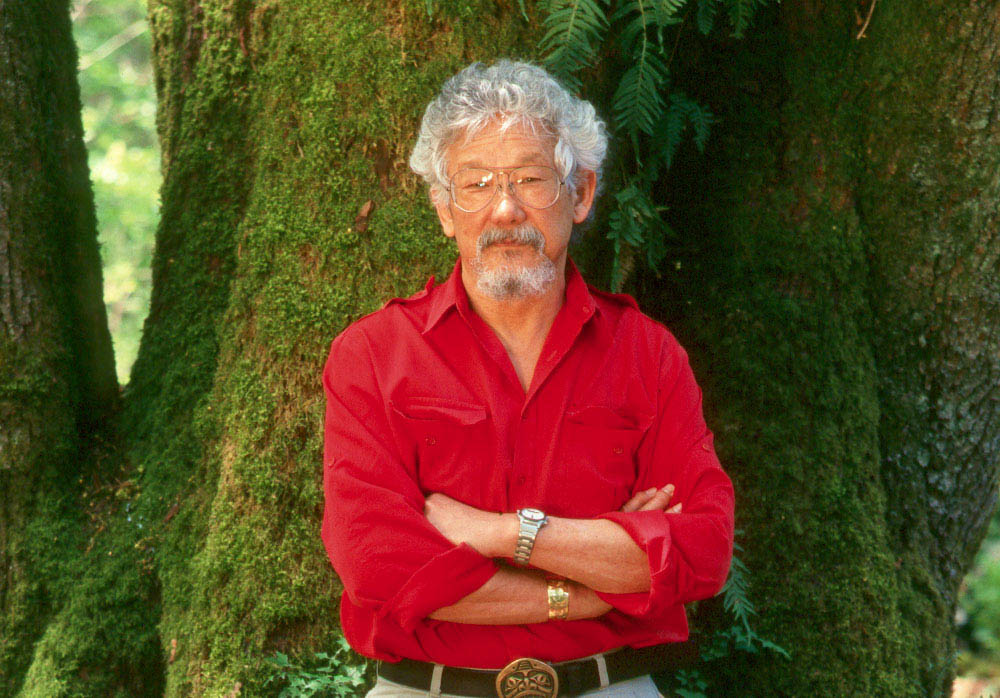

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Senior Writer and Editor Ian Hanington.