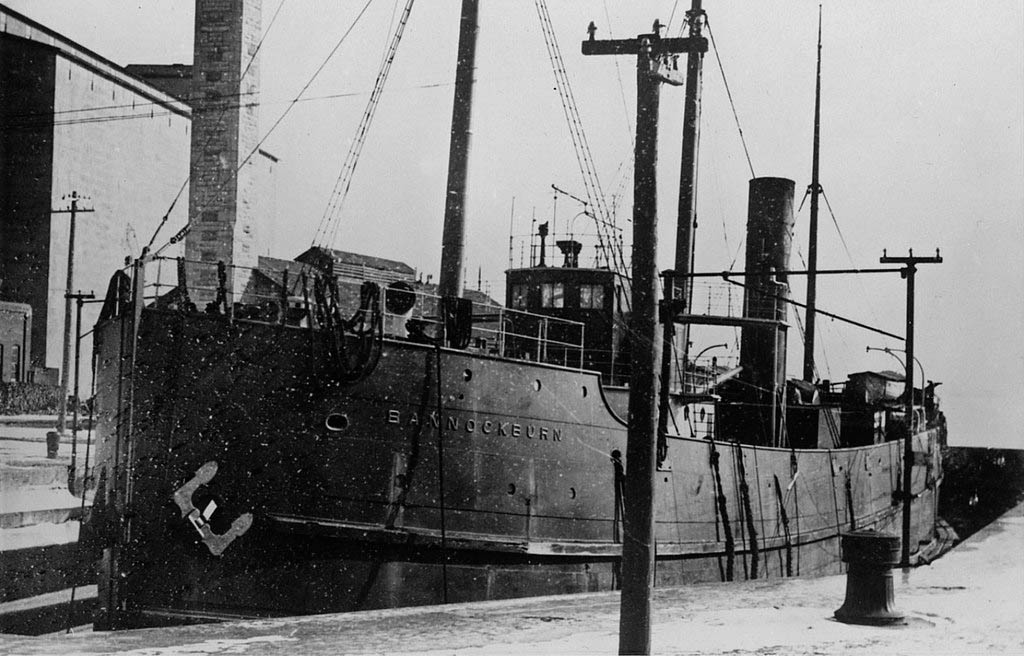

During a storm in November 1902, the propeller-driven bulk freighter Bannockburn went missing with 20 men in Lake Superior. The Bannockburn, often known as the “Flying Dutchman” of the Great Lakes, is said to be a ghost ship that has been sighted on the water several times since its disappearance.

The steamer Bannockburn was a steel-hulled freighter registered in Canada that went missing on Lake Superior in inclement weather on November 21, 1902. Around noon on that day, she was spotted by the captain of a passing vessel, the SS Algonquin, but she vanished minutes afterwards. With the exception of an oar and a life preserver, the shipwreck was never discovered, and no corpses were ever retrieved. She gained a reputation as a ghost ship and was dubbed “The Flying Dutchman” of the Great Lakes within a year of her absence.

“As the waters of Lake Superior reach their greatest depth at that point it is probable that none of the bodies will ever be recovered. Lake Superior never gives up its dead,”

Detroit Free Press Dec. 2, 1902

The Bannockburn had technically sunk once before, on the morning of October 15, 1897, when she struck the wing wall of Lock No. 17 of the Welland Canal and sprung a leak, sending her to the bottom of the shallow canal where she took on nine feet of water before coming to rest, laden with grain and destined for Kingston, Ontario from Chicago, Illinois. No lives were lost, though, and she was raised afterward. She had also been heavily damaged many months before when she hit the rocks near Snake Island Light while at full speed on the morning of April 27; however, after emptying 30,000 bushels of grain cargo, she was able to float and no lives were lost.

Captain George R. Wood launched the Bannockburn’s final journey from a Canadian Lakehead in what is now Thunder Bay. She was on her way to Georgian Bay, carrying 85,000 bushels of wheat, and she left Fort William on November 20. On her way out to the open lake, she had a minor grounding but no visible damage, thus her departure was postponed one day. On the 21st, she resumed her trek. Captain James McMaugh of the upbound Algonquin, a lake freighter, reported seeing her with binoculars around 7 miles (11 kilometres) southeast of him, about 80 miles (130 kilometres) off Keweenaw Point and 40 miles (64 kilometres) off Isle Royale, during that day. McMaugh attempted again to locate her at one point and was astonished when he was unable to do it. He downplayed the unexpected absence by blaming it on the gloomy weather.

That night, Lake Superior was ravaged by a strong winter storm. At 11:00 p.m., the nigh watch pilothouse crew of the passenger steamship Huronic, which was also upbound on the lake, reported seeing lights on a ship they passed in the storm that they thought were similar to the Bannockburn’s. There were no distress signals, however, and the two ships passed each other without incident. The Bannockburn was reported overdue reaching the Soo Locks the next morning, although given the weather the night before, this was not surprising. However, when she failed to report after many days, the suspicion that she had gone missing grew.

The steamer John D. Rockefeller passed through a field of floating debris near Stannard Rock Light on November 25, which could have been the wreckage of the Bannockburn, though the Bannockburn had not yet been reported missing and the Rockefeller’s crew had no idea what had caused the debris field. The ship and crew members of the Bannockburn were officially declared “lost” on November 30.

There are numerous explanations for what went wrong. Captain McMaugh (Algonquin) speculated that the ship may have been involved in a boiler explosion, despite the fact that he did not hear one and no burned wreckage typical of such an explosion was later discovered anywhere along the Bannockburn’s known course. Alternatively, the Superior Shoal’s as-yet-undiscovered hazard could have been the cause. A hull plate from a ship was discovered in the Soo locks when they were drained at the end of that season. It was supposed to be part of the Bannockburn’s hull, and without it, the ship’s hull would have had an unknown weak point.

Captain Wood, from Port Dalhousie, Ontario, was the vessel’s oldest occupant, at 37 years old. The team was mostly made up of people between the ages of 17 and 20. Arthur Callaghan, one of the ship’s two wheelmen, was only 16 years old. Despite the fact that the ship was relatively new (it had been built only nine years), the overall inexperience of her crew may have contributed to her loss. Such youthful crews, on the other hand, were common on the Great Lakes around the turn of the century because they were cheap to hire, and shipping companies had strong financial incentives and no legal reason not to utilize them whenever they could.

Another theory about the Bannockburn’s disappearance stemmed from the fact that the ship had stranded on Caribou Island. The lighthouse on this island is surrounded by a dangerous reef, and its warning light was intentionally turned off on November 15. If the captain of the Bannockburn had hoped to spot it in the darkness of the storm on November 21, the only evidence he would have had of his approaching proximity would have been the shock of the hull striking the reef.

The disappearance of the Bannockburn, which has allegedly been observed by modern freighters and has been the subject of several ghost stories, is one of the most well-known missing ships on the Great Lakes.

With an average depth of 500 feet to 1,332 feet, Lake Superior is the deepest and coldest of the Great Lakes. With today’s amazing technology assisting humans in diving deeper, exploring with less effort, and discovering troves of lost ships, the Bannockburn may one day be discovered and end the “Flying Dutchman” sightings!