Meeting the needs of eight billion people is a serious challenge. Meeting the “wants” of those tied to political and economic systems based on endless growth, consumption and waste makes it daunting.

Our growing population’s unceasing appetite for luxury living, the latest electronic devices, up-to-date fashions, meat-rich diets and private automobiles and the infrastructure to support them has left little of the world untouched. (Of course, the wealthiest nations and people are most at fault.)

A study in Frontiers in Forests and Global Change concluded that less than three per cent of Earth’s land base remains “intact” — much of it in remote areas of Canada, Russia and Greenland, with patches in Indonesian and Amazon rainforests and the Congo Basin. (Antarctica was not included.)

According to Smithsonian Magazine, “The study takes into account three measures of ecological integrity: habitat intactness, which is how human activity has affected the land; faunal intactness, which looks at species loss; and functional intactness, which focuses on species loss among animals that contribute to the health of an ecosystem.”

Even the intact areas are threatened by human activity, from mining and agriculture to climate disruption. The bright spot is that restoration efforts could push the global area “with full ecological integrity” to almost 20 per cent by re-introducing five or fewer important species in undamaged habitat where they’ve been lost.

Report co-author and Key Biodiversity Areas Secretariat technical officer Daniele Baisero points to the role key species play in everything from seed dispersal to regulation of prey animals. “When these are removed, the dynamics can vary and can sometimes lead to ecosystems collapsing. The reintroduction of these species can return a balance to the ecosystem,” he told CNN.

Many people are familiar with how bringing wolves back to Yellowstone National Park set off a chain of events leading to healthier, more balanced ecosystems. It’s an example of “rewilding,” as restoration and conservation aren’t always enough.

Rewilding efforts can range from relatively small, localized interventions, such as re-introducing key species, to massive reforestation projects, with a lot in between.

The Affric Highlands initiative plans to rewild about 200,000 hectares in the Scottish Highlands over 30 years by “planting trees, enhancing river corridors, restoring peat bogs and creating nature-friendly farming practices,” a Guardian article says. “The idea of doing it at scale is that you get a much bigger natural response because you’ve got room for change and dynamism in that landscape,” said Alan McDonnell, project leader and conservation manager at non-profit Trees for Life.

It still faces a number of hurdles, but it’s not the first rewilding initiative in the area.

Sometimes rewilding involves taking down barriers. On the Olympic Peninsula, just south of my home, removing 100-year-old dams from the Elwha River 10 years ago brought growing numbers of steelhead and salmon back, and increased bull trout numbers. That attracted birds and other animals that eat the fish, and is expected to boost forest health as animals drag nutrient-rich fish into the trees. Crews also planted hundreds of thousands of native species to help restore former reservoir bottoms.

The efforts are thanks in large part to the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, who’ve fished the salmon for millennia. Jessica Plumb, whose film Return of the River documents its transformation, wrote in Orion, “The rewilding of the Elwha is a story of environmental justice, equal in scope to the scale of restoration.”

The UN and 195 member nations set a target under the Global Biodiversity Framework to protect 30 per cent of the world’s land and ocean by 2030. Meanwhile, Indigenous Peoples worldwide are leading efforts to conserve, protect and rewild their traditional territories. But it’s an uphill battle as long as human societies measure success and progress by how much we spend and consume.

Rewilding projects show how quickly nature can bounce back once we set things right and get out of the way. They can also help restore justice, provide hedges against climate disruption, flooding and soil erosion, and offer benefits ranging from recreational to agricultural to economic opportunities.

We can’t continue to degrade and destroy the natural systems that our health and lives depend on for the sake of illusory ideals of progress. It’s time to go wild.

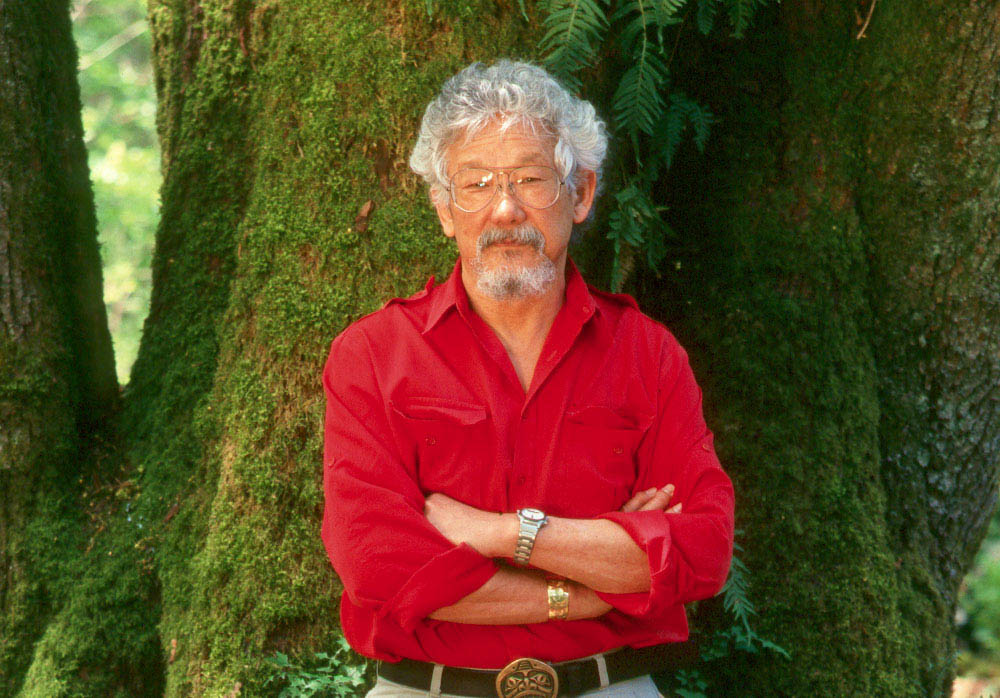

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Senior Writer and Editor Ian Hanington.