Would you buy cannabis gummies from me? Apparently, hundreds of people would. Only trouble is, I don’t sell them, and I’m not looking for business opportunities. But recent online memes, stories and other disinformation have me not only selling and endorsing CBD gummies but also embroiled in a lawsuit with businessman Kevin O’Leary over them!

People see the bogus information, click through to a realistic product page, submit their personal and financial information and order the products. It appears they most often find the pitches on Facebook.

I’m saddened that anyone would spend money hoping to purchase products they thought I manufactured or recommended. The scam is still tricking innocent people. They contact the David Suzuki Foundation daily.

This got me reflecting on how and where people receive and process information. I’ve been a science communicator for more than half a century, so I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about how to get through to people. How do we ensure as many as possible have access to accurate, credible information so we can make informed decisions on issues that matter?

I’ve been fortunate to have worked many years at the CBC. As a public broadcaster, it’s been producing quality content and upholding journalistic standards since before the Second World War — and helped me earn credibility as a communicator.

Today, I compare that type of relationship — one based on accurate and fair communication of relatively diverse types of evidence and viewpoints — to what I see online, on social media, and it’s shocking. False information and scams abound, along with the worst political polarization in recent memory.

Fraud and misinformation have been around as long as we have, and perpetrators have always seized on the best available technologies to reach people. But in under 30 years, the internet has become our main information source, and the ubiquity of social media has given rise to effective, inexpensive ways to spread information, from bad to good and everything in between.

Close to 60 per cent of the world’s population — 4.66 billion people — are active internet users, most accessing it through mobile devices. It infiltrates and informs every aspect of our lives.

As Marshall McLuhan posited in the 1960s, our technologies have become extensions of ourselves.

As these systems evolve and become more powerful, complex and efficient, so too must our collective ability to understand and use them.

As we receive more information online — from recipes to weather forecasts, product info to politics — how can we make sure it’s reliable, that we can trust it enough to make good decisions? If we’re wrong, what’s at stake? Many people search for or are fed information that confirms their beliefs rather than that which could help them better understand an issue. And, as recent vaccine opposition reveals, much of it promotes “personal freedom” while ignoring the responsibility that goes with it.

In today’s digital society, media literacy levels must match the sophistication of mass communication methods and big tech. But this isn’t the case, and we’re seeing the consequences, from increasing polarization to revelations about how platforms like Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp foment division and conflict in the name of profit.

Environmentalists encounter the misinformation problem often. In 2021, a dwindling minority still reject the validity of climate science, despite an astounding amount of evidence proving the crisis is upon us and massive international scientific consensus regarding the urgent and necessary path forward.

How can we come together, have informed conversations and enjoy the benefits of evidence-based decision-making? It’s clearer than ever that a democracy works best when people have access to accurate, credible information.

We must see our information systems — news media, social media, etc. — as the foundations of democracy they are, and we must insist on keeping them, and the people who use them, healthy.

We should invest more public resources in ensuring our media industry is healthy, social media is properly regulated and most people are media literate enough to consume online information safely and responsibly. And we must take responsibility and get better at synthesizing information, considering various perspectives and uniting behind solutions to the world’s biggest problems.

It all begins with productive, respectful conversations based on good information. (And maybe some CBD — but not from me!)

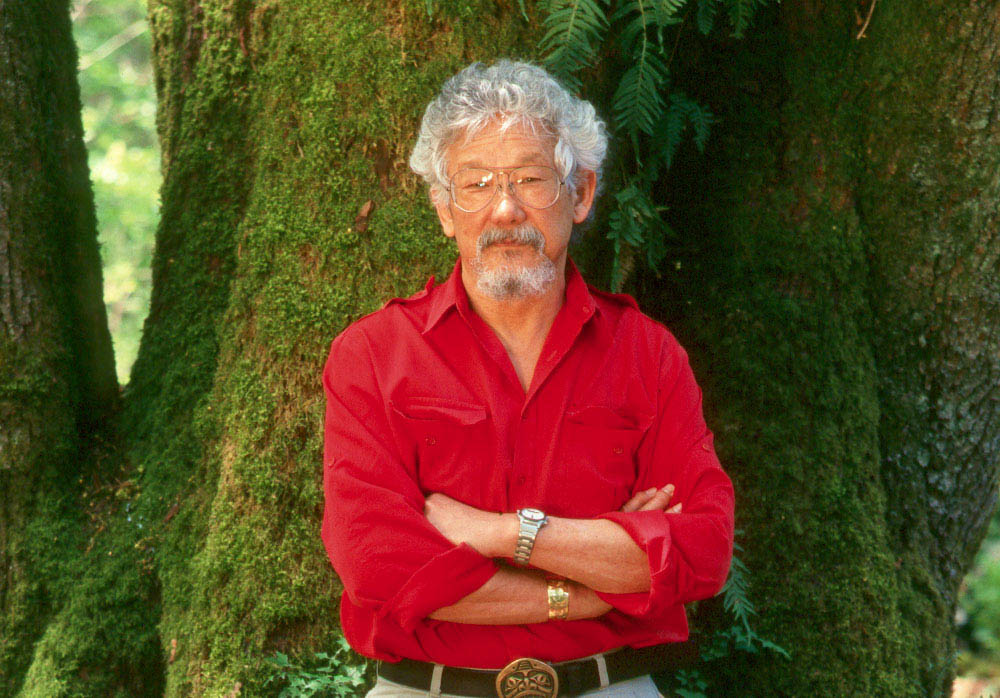

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Communications Director Brendan Glauser.