According to philosopher-historian Yuval Noah Harari, “Homo sapiens conquered this planet thanks above all to the unique human ability to create and spread fictions. We are the only mammals that can cooperate with numerous strangers because only we can invent fictional stories, spread them around, and convince millions of others to believe in them. As long as everybody believes in the same fictions, we all obey the same laws, and can thereby cooperate effectively.”

In his book, Sapiens, Harari explains that 1,000 humans can peacefully occupy a large room if it’s for a common purpose — to attend a lecture, say, or church. But if you put 1,000 non-human animals into a room, chaos would likely ensue. (Of course, human gatherings can also end in chaos.)

This is the most convincing theory to date of a distinction between humans and non-human animals — a distinction we’re so heavily invested in that we’ve told ourselves numerous stories to uphold the concept. Most of these stories have been debunked.

In the 1960s, Jane Goodall rocked the scientific world by reporting that David Greybeard, a chimp she was observing, used grass stalks to collect termites from a termite mound. Until then, tool use was thought to be a defining quality of humanity. In subsequent observations, she noticed chimps shaping tools to increase their efficiency. In response, her sponsor Louis Leakey exclaimed, “Now we must redefine tool, redefine Man, or accept chimpanzees as humans.”

Instead, we shifted the goalposts, and asserted that while other animals might make and use tools, only humans had a sense of self. This theory was discounted by the “mirror test,” first conducted in 1970, in which Gordon Gallup Jr. anesthetized apes, painted a red spot on their foreheads, and placed a mirror in their cage. When they came to, the apes responded by touching the spot and inspecting their fingers, much as humans would do.

While American linguist and social activist Noam Chomsky and his supporters assert that language differentiates humans from other animals, and while humans have never successfully taught other animals to communicate in complete sentences, there’s little question that animals communicate. Honeybees dance out directions to nearby nectar. Vervet monkeys use different alarm calls to alert fellow monkeys to the presence of leopards, eagles and snakes.

Researcher W. Tecumseh Fich says animals communicate complicated ideas within their communities, but this “cognitive sophistication” isn’t detectable in their vocal communication systems.

The assertion that only humans can think abstractedly has also been debunked, as has the notion that only humans have culture and shared learning.

There’s no question that non-human animals are different from humans in many ways. But although we can’t teach a chimpanzee how to communicate with us in sign language as a human could, nor can we learn how to communicate within non-human animal societies. While we might glean the meaning of some of their signals and cries, many concepts they comprehend are collectively understood in ways we’ll likely never know.

As our stories evolve or are replaced as we learn from the world around us, we must find narratives that better equip us to meet the challenges of our times. Our current preferred plot lines potentially hinder our ability to fully come to terms with risks such as those posed by climate change and the steps needed to address them. Harari writes, “It’s important to have human enemies in order to have a catchy story. With climate change, you don’t. Our minds didn’t evolve for this kind of story.”

As dictators have shown throughout history, collective narratives are often successful when they have a bad guy, someone or something that is “other.” That’s why seeing nature as a “resource” rather than “kin” or something we are a part of has made ecosystems easy to exploit.

Ultimately, humans have the ability to shift our narratives, create wider circles of caring and revel in the wonders of non-human animals’ abilities instead of comparing them to ourselves and finding them lacking.

It’s not too late to set ourselves up to be the story’s heroes who finally take responsibility for our ailing planet. In the most pressing story facing our planet today, the ending has yet to be written.

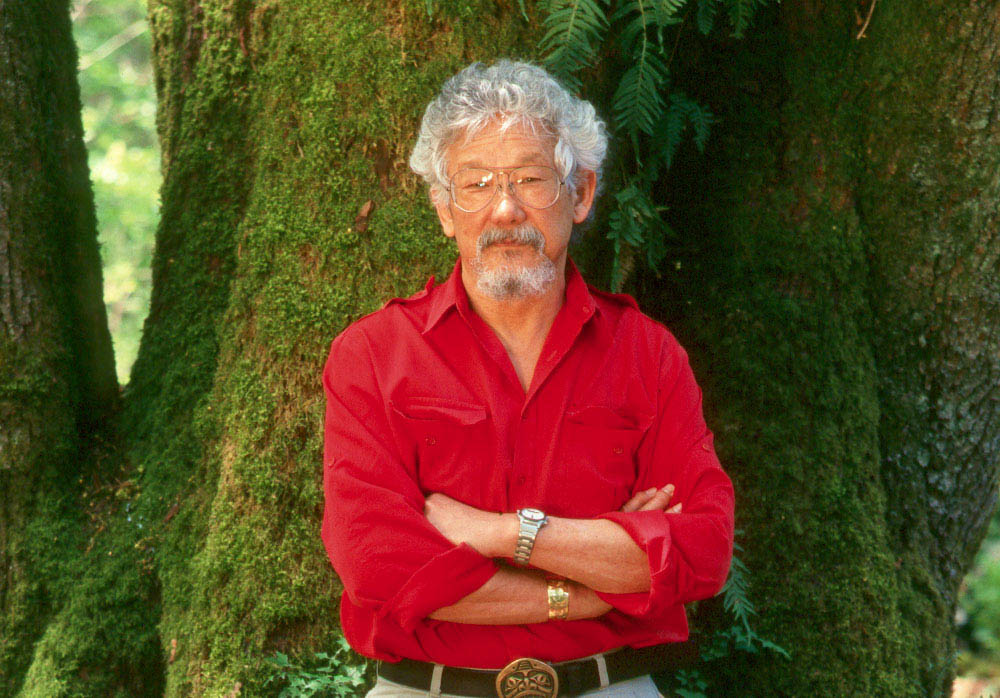

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Boreal Project Manager Rachel Plotkin.