The longer we put off seriously addressing climate disruption’s causes, the more we’ll have to adapt to unavoidable consequences. Those who have been bleating that getting off fossil fuels will be too expensive are in for a surprise: adaptation can be far costlier than mitigation, and without the latter, we’ll have to accelerate the former — and we still can’t avoid doing what we should have started 35 years ago: quitting coal, oil and gas.

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assessment report, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, shows we’re at a point when the choice isn’t between one or the other. We must do everything to reduce the worst effects of climate disruption and adapt to the damage we’ve already locked in with our profligate burning of fossil fuels and destruction of carbon sinks like forests, wetlands and peatlands.

This is the second of three working group reports, which — along with three special reports and a synthesis report — make up the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report. The first section, released in August 2021, assessed the physical science and provided overwhelming evidence that “climate change is widespread, rapid and intensifying.” The third, expected in March, will be on climate change mitigation.

As the IPCC shows — and as anyone can see — we’re already living with impacts, and they’ll worsen if we fail to change: more heat domes, wildfires, intense weather events, flooding, drought and extreme heat.

As for “vulnerability,” we know the climate crisis is disproportionately affecting those who have contributed to it the least. Through excess consumption and unsustainable lifestyles, wealthy people and nations continue to speed the trajectory to climate chaos. They also have more resources to insulate themselves from the impacts, although no one will be immune to the mounting consequences.

The report contains slivers of hope, though. One is that some key methods of adapting to climate disruption will also help prevent it from accelerating beyond our control. That’s because a major contributor to climate change, outside of burning fossil fuels, is destruction of natural systems that sequester carbon and help keep the carbon cycle balanced so human and other life can flourish. Protecting and restoring terrestrial, freshwater, ocean and coastal ecosystems can help draw out and keep carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and protect against now-unavoidable impacts.

For example, although adapting to sea level rise sometimes means employing strategies like “managed retreat” or building infrastructure such as seawalls, it can also include restoring coastal ecosystems to absorb the impacts of events like storm surges and flooding.

Adaptation also means ensuring strategies don’t disproportionately affect the most vulnerable people and communities. The IPCC report notes this includes economic diversification, technologies and strategies that strengthen resilience, reduce inequalities and improve climate-related human well-being.

It’s not just about addressing an existential crisis. Adapting to and preventing the worst impacts of climate disruption will create a better society for everyone everywhere, with less inequality and waste, and with recognition of and respect for the importance of nature, of which we’re a part.

A world with billionaires, let alone those who can rocket into space — or worse, start planet-threatening wars — while so many people lack life’s basic necessities, is a world out of whack. When we evaluate human “progress” according to how much we spend and consume, with little or no thought to actual well-being, something isn’t right. When we view economic and population growth as necessary and good, even though our planet and all it has to offer are finite, it’s impossible to imagine a sustainable future.

The climate scientists and experts who compile the IPCC assessments examine the current and most relevant science regarding all aspects of the crisis. Assessments must then be agreed upon by the 195 member countries and jurisdictions (only a few countries have not formally signed the IPCC’s 2015 Paris Agreement). Final reports tend to be conservative and watered down in order to garner agreement.

Since the first assessment in 1990, evidence and certainty have become incontrovertible. This report, and the Sixth Assessment as a whole, show that we have no time to lose, that we must employ the many available and emerging solutions before it’s too late. Doing so will usher in a better world for all.

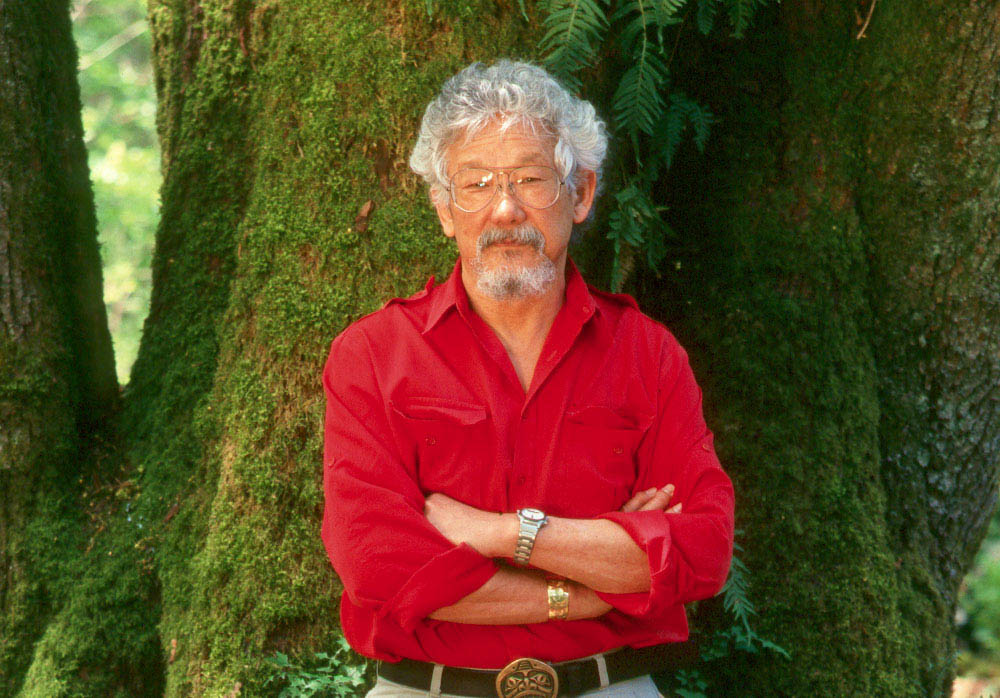

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Senior Writer and Editor Ian Hanington.