Taking images of fish is probably one of the most difficult and frustrating kinds of Underwater Photography, and yet one of the most rewarding. Almost every underwater photographer, at one time or another, has looked at fish pictures in dive magazines or online, and has wondered how the photographer was able to capture the image. Great images of fish require a combination of factors, including research, planning, competent diving skills, solid photographic techniques, patience, and a bit of luck. When I teach underwater photography, I tend to stress simplicity. First, you should concentrate on isolating a single subject or multiple subjects. To get really dramatic images you usually have to get close to your subject. So the old adage, “Get close, Get down and Shoot up”, definitely applies.

One of the most important lessons to learn in this endeavor is to find out as much as you can about the marine life you’re trying to photograph. This gives you a better chance to get closer and will drastically improve the likelihood of obtaining an excellent image.

Fish Behavior

Once you become very comfortable underwater, you’ll be able to devote more effort to the thought processes required for underwater photography. Learning about fish behavior is an essential tool in the process of becoming a consistently competent fish photographer. What a fish feeds on, where it hangs out, fish hygiene, and mating behavior are just a few of the bits of helpful information that you may need. The more you find out about particular fish, the better your chances will be to get close enough to take a great photograph.

Mating Rituals and Behavior

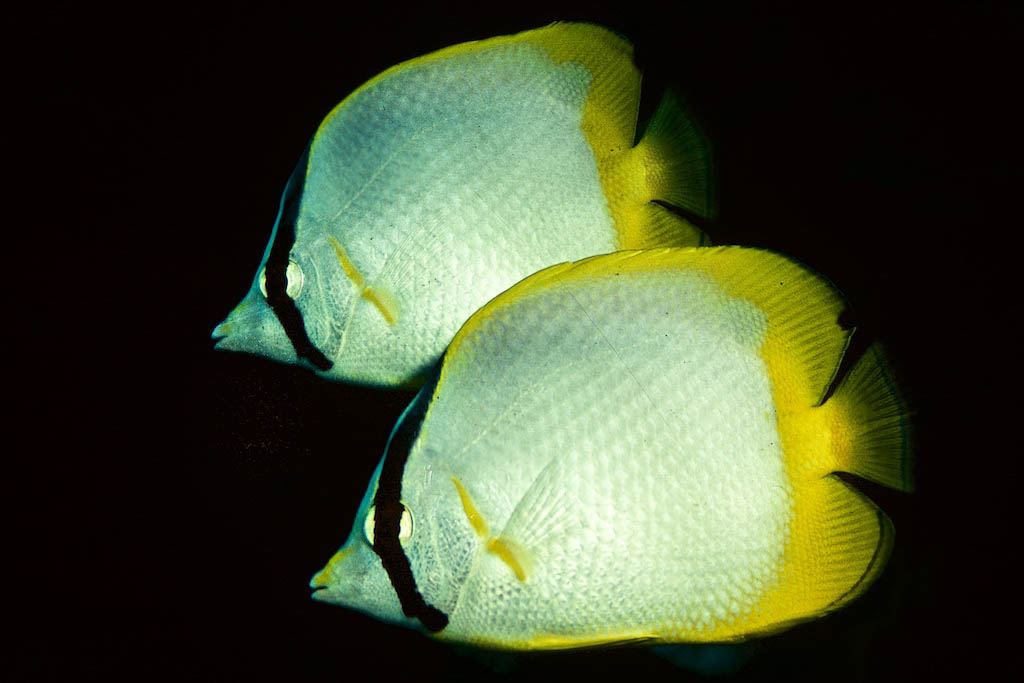

If a fish is concerned with attracting a potential mate, that fish will probably ignore your presence, even if you have a bright yellow and pink dive skin with matching accessories and your movements are a bit too jerky. If a pair of fish are in the process of spawning or at least dating, it is pretty likely that you will be overlooked regardless of what you’re doing.

A good example is the strikingly beautiful Mandarinfish that can be found throughout the Indo-Pacific. They are very territorial and tend to congregate in the shallow coral rubble beds and finger corals. Night dives are often set up with the specific purpose of beginning the dive in an area where Mandarinfish are known to hang out. These dives always need to start before the sun goes down, because Mandarinfish will emerge at dusk to participate in their courtship dance. These smallish fish will pair off and rise up in the water column to perform a flashy courtship dance, and with the female resting on the male’s pelvic fin they will spawn, releasing a cloud of eggs and sperm. This is generally the easiest time to take your photos.

If a fish is guarding its eggs or neatly manicuring its nest, it may ignore you as an unlikely predator or perhaps try to chase you off. In either case, you may be able to get up close and personal and be able to take the photograph.

Territoriality

You may find that many fish are territorial, but for different reasons. Some, like the male Garibaldi in southern California, will clear a sheltered nest site and will protect that site from all intruders including divers. Large Triggerfish, which can be found in most tropical dive destinations, will protect their nests against all who venture too closely. All types of triggerfish build nests on the open sea floor, and will try to chase away other fish or divers who venture too close. Titan Triggerfish have a particularly bad attitude. During the reproduction season the female guards her nest vigorously against all intruders, escorting them away from the nest and on occasion inflicting a serious bite. The threat posture includes facing the intruder and holding its first dorsal spine erect. For photographers, this may be good or bad depending on whether it involves being able to get ‘the shot’ or get bitten.

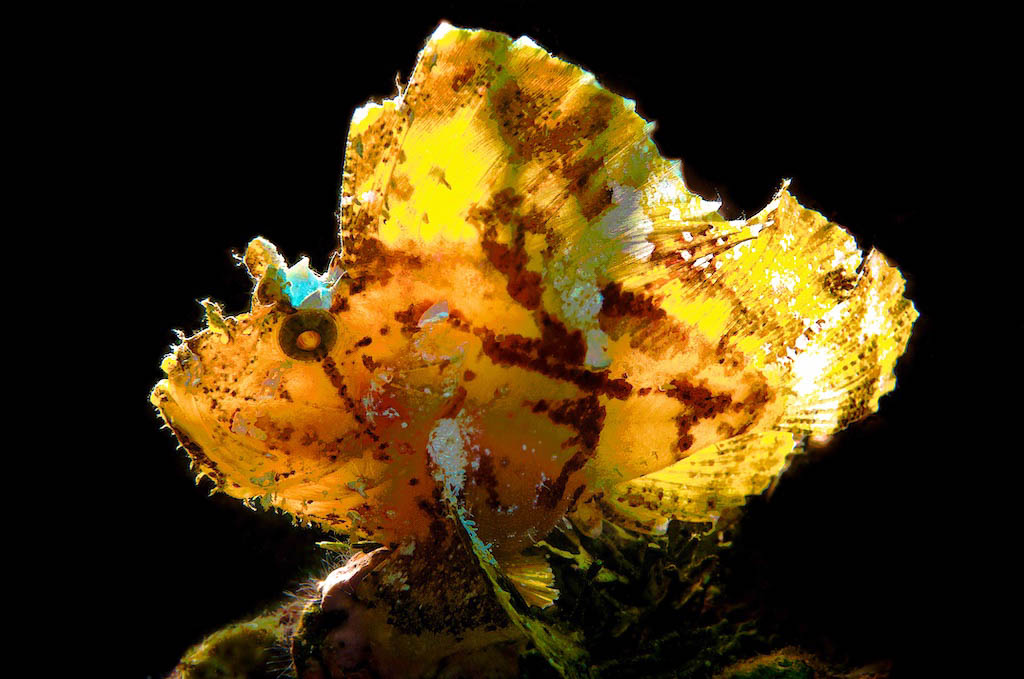

Many other tropical fish, such as frogfish and scorpionfish are also very territorial, and they can often be found in the same location or general area for several weeks at a time. These fishes often rely on camouflage to mask their presence from others. There may be particular places on the reef such as low-lying caves or overhangs where certain types of fish can usually be found. Anemonefishes can always be found living within the protection of their host’s stinging tentacles. A few anemonefishes can be found in the water column, high above their host anemone, and are pretty cooperative about posing.

Night dives

Night dives often provide opportunities to get close to fish that are too active and skittish on the reefs during the day. While many of these fish are docile or inactive at night and easier to approach, they sometimes completely change colors and patterns. Among the fishes that are particularly fun to photograph at night are spiny pufferfish. While they are generally pretty elusive during the day, at night they can often be found hanging out in small sandy alcoves or depressions along the edges of shallow reefs. Although they won’t swim away at night, they do have an understandable albeit frustrating habit of turning their bodies away from the camera. Try shining your spotter light in front of them, and they will often turn around and swim back toward you.

Personal hygiene (Cleaning Stations)

If you find a cleaning station, you may observe that many species, which are often difficult to approach, may be more inclined to pose for a picture. Fishes that congregate around cleaning stations are normally very civilized. When it’s time to get those unwanted parasites or nasty bits of dead skin removed, many fish will queue up and wait their turn for cleaners to do their job. Cleaners most often include gobies, shrimp and juvenile reef fish. I have never observed any disorderly conduct between fishes hanging out in the waiting room. If you feel like you need a little pruning or other work done, try putting your hand near a bunch of cleaners. Just wait your turn!

Research the dive site

The more you find out about a particular dive site, the more you can do to take full advantage of the photo opportunities offered at each location. Ask your divemaster or other divers who have visited the site previously what to look for. They might give you some useful info about some of the resident fishes that divers might be able to get close to. Some reef residents are such picture hogs that they can get downright annoying. Certain fish in the Caribbean often swim back-and-forth between the photographers and their intended subjects. Gray angelfish are well-known for this behavior. Sometimes you may find a dive master or underwater photographer who is willing to share the location of a rare or hard to find fish that he or she saw on the last dive or that they are pretty sure hang out in a certain place on the reef.

Diving and photographic techniques

There may be certain diving or photographic techniques that make dramatic fish portraits a lot easier to achieve. You don’t know how many images you will be able to take in a sequence. If you set up for a shot ahead of time it will increase your chances to get at least one good image of a skittish subject. If you are using manual exposure settings, take a ‘pre-shot’ to test the exposure before you approach your intended subject. The easiest way to do this is to take a quick shot of a sponge or hunk of coral. Take a look at the exposure and quickly adjust your settings (shutter speed, aperture, and ISO) to lighten or darken the image. Then go ahead and approach the fish and take a quick image. If the fish cooperates, and you have the opportunity to take multiple images, then you can concentrate on composition rather than adjusting exposure. When you approach your subject, try to anticipate the fish’s movement so that you can maximize your chances of getting an interesting frontal shot. If you know that your exposure is in the ball-park, you can bracket while focusing on the eyes of the fish, using different camera angles. If the fish is angling toward you, make sure that your strobe(s) will be able to light the side of the fish that is visible to the lens.

Don’t Scare Your Subject

This is probably an obvious point, but successful fish photography depends upon getting close enough to the subject to get the picture you want. If you chase the subject, you will only become proficient at great tail shots. There are several alternatives to trying to out-swim your subject. Always use exaggerated slow movements and move parallel to your subject. Even though some fish are relatively slow swimmers, you will find that when they’re startled by a diver’s quick, jerky hand or body movements, they can still move a lot faster than you can. They will often slip into cracks and crevices that are a bit too small for you to follow them.

If you swim parallel to your intended subject, you’ll often find that you can take repeated side shots or move down the reef ahead of the subject and wait for it to swim to you. Also, spend as much time as possible in one area to let the fish get accustomed to your presence. This may also let you learn more about their behavior by observing. Some fish, like juvenile spotted drums found in the Caribbean, are always in motion, and at first blush it can seem like photographing them can be a study in frustration. Take a bit of time to observe their movements. You will find that they often swim in repeated patterns, such as a figure eight, in the same area. Anticipate where they will be and set up your shot from an angle that will allow the fish to come to you. This technique also works very well with most anemonefish, that are in constant motion around their host anemone.

Simplicity

In most situations, the fish portrait is much more dramatic if you can keep it simple. Concentrate on a single subject or pair of subjects. Isolate the subject (s) against an uncluttered background. Try using a horizontal or slightly upward angle whenever possible. By doing so you can often get a background that is mostly water, giving you a solid blue or black background.

Before trying to shoot multiple subjects, concentrate on getting a single fish by itself. Be creative with your lens to subject angles. Remember that the most interesting shots will probably be those where the fish is swimming toward the lens or appears to be coming into the frame. Try to put some open space between the front of the fish and the side of the frame. This will add to the impression that the fish is entering your picture.

Get low, Get close, Shoot up

Finally, in most instances it will improve your photo if you think “get low, get close, and shoot up.” Try to avoid shooting down on your subject. Shooting down inevitably causes problems. At best it usually results in adding clutter to the background. Get as low as possible so that you can either observe the fish at its level or look up at it. Most fish will agree that this gives them a much more distinguished appearance. Putting a solid color, such as blue water or a simple pattern, such as a Sea Fan, section of coral, or Feather Star, behind your subject, helps to isolate and frame it in the picture.

In some situations, you simply can’t avoid a cluttered background. Get as close as possible to the subject to minimize the background details. You can also try to collapse the depth of field around your subject, leaving your subject in focus and blurring out the distracting background detail. The smaller the aperture the thinner the depth of field.

Practice these tips to enable you to get closer to your subject and to simplify your images. I think you will be pleased with the results in most cases. After you have absorbed all the technical information you can, you will find that the most important elements of fish photography are still good diving skills, solid photographic techniques, patience and LUCK!

For more interesting facts on fishes and other marine animals, check out our series of eBook Dive Travel Guides. Go to our website to get links to Amazon, iTunes and Google Play platforms and take advantage of free downloads that may be available: https://www.divetravelguides.com