According to many shipwreck historians, the Titanic is still the deadliest peacetime sinking of a superliner or cruise ship. The disaster drew widespread public attention, laid the groundwork for the disaster film genre, and inspired numerous artistic works. Its relationship with Canada is well known.

The majority of the bodies recovered were unloaded at the Coal or Flagship Wharfs on the Halifax waterfront, and horse-drawn hearses transported the victims to the Mayflower Curling Rink’s temporary morgue. Only 59 of the bodies in the morgue were returned to their families by train. Between May 3 and June 12, the remaining bodies from the morgue were buried in three Halifax cemeteries. The White Star Line paid for the majority of the gravestones, which were erected in the fall of 1912. However, in some cases, families, friends, or other groups decided to commission a larger and more elaborate gravestone. Fairview Lawn Cemetery contains all of these more personalized graves, including the striking Celtic cross and the lovely monument to the “Unknown Child.”

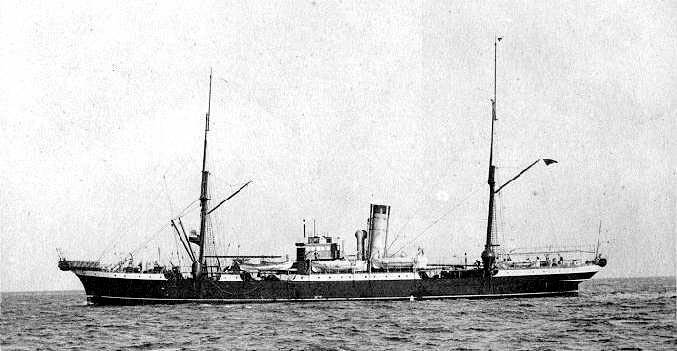

The Mackay Bennett, which was based in Halifax, Nova Scotia at the time, is known among historians. It is best remembered as the ship that recovered 306 of the 328 bodies in the water after the Titanic disaster.

About the Mackay Bennett

The Mackay-Bennett was a transatlantic cable-laying and cable-repair ship registered as a Glasgow vessel with Lloyds of London but owned by the American Commercial Cable Company. It is best remembered afor the ship that recovered the majority of the bodies of the Titanic’s victims.

The ship was commissioned at Fairfield Yards by the USA-based Commercial Cable Company from the then-famous River Clyde-based warship builders John Elder & Co. The company incorporated a number of novel and innovative features into the cable ship at the time. It was one of the first ships constructed of steel rather than iron, and she had a relatively deep keel design to accommodate as much cable as possible while also keeping the ship stable in Atlantic Ocean swells. The design was also very hydrodynamic in order to keep her running efficiently and quickly. To keep her stable, the hull design included bilge keels, and she had two rudders, one fore and one aft, to maximize maneuverability. She was launched late in 1884 and named after her owners’ two founders. Her name was pronounced “Macky-Bennett” by her crew.

Due to the nature of her work and the resultant position in the Atlantic, Mackay-Bennett performed numerous rescues in addition to carrying out numerous difficult cable repairs, many of which occurred during times of wartime danger.

She was berthed in Halifax in April 1912 for a long period of work to maintain the France-to-Canada communications cable. Only the Mackay-Bennett, one of the three ships in Halifax at the time, had a hold large enough to hold the 125 coffins and ice used in the exercise to recover bodies. The ship rose to prominence as the primary vessel contracted by White Star Line to carry out the difficult task of recovering the bodies left floating in the North Atlantic following the Titanic disaster.

The task was fueled further by Joseph Astor’s announcement of a $100,000 reward for the ship that recovered his father’s body; J.J. Astor. Her captain, Frederick H. Larnder, brought on board a team of specialists as well as a mobile mortuary. For the assignment, additional and specialized personnel and supplies were brought on board. This included:::

- Canon Kenneth Cameron Hind of All Saints Cathedral, Halifax

- John R. Snow, Jr., the chief embalmer with the firm of John Snow & Co., the province of Nova Scotia’s largest undertaking firm, hired by White Star to oversee the embalming arrangements

- Sufficient embalming supplies to handle 70 bodies

- 100 coffins

- 100 long tons of ice, in which to store the recovered bodies

The crew received double pay for the gruesome task. Because the ship could never hope to bring everyone back, the mortuary details were organized in a hierarchy: first-class passengers were embalmed and placed in coffins; second-class passengers were wrapped in linen winding sheets; third-class bodies were weighted and buried at sea (116 in total).

On Wednesday, April 17, 1912, at 12:28 p.m., the ship departed Halifax. Due to heavy fog and rough seas, the ship took nearly four days to travel the 800 nautical miles (1,500 km; 920 mi) to the disaster site. The captain instructed the ship’s crew to keep their logbooks complete and up to date during the voyage and subsequent recovery operation, but only two logbooks are known to have survived: seven pages from engineer Frederick A. Hamilton’s logbook, now kept in the National Maritime Museum, England, and Clifford Crease’s personal diary, a 24-year-old Naval artificer (craftsman-in-training) now held in the Public Archives of Nova Scotia.

The ship arrived during the night, so body recovery began at 06:00 on April 20. The CS Mackay-Bennett was anchored near but not in the recovery area, and she unloaded her skiff lifeboats. Crews then rowed into the recovery area and recovered the bodies manually into the skiffs. The crews rowed back to the CS Mackay-Bennett after recovering as many bodies as they deemed safe for the return journey (51 corpses). The captain noted that there was not enough space aboard to store all of the recovered bodies, nor were there enough embalming supplies. Because the Canadian Government and associated burial and maritime laws required that any bodies carried be embalmed before a ship could enter a Canadian port, the captain agreed.

First-class passengers were embalmed, placed in coffins, and stored in the cable locker at the back of the ship. Body No.124 recovered on 22 April was that of John Jacob Astor IV, the richest man aboard, identified by his unique diamond finger ring and the initials sewn on the label of his jacket; architect Edward Austin Kent, body No.258; and Isidor Straus, owner of Macy’s Department Store.

Second-class passengers were embalmed, canvas-wrapped, and stored in the forward cable locker.

A total of 116 third-class passengers were buried at sea. In October 2013, a photograph taken by Fourth Officer R. D. “Westy” Legate of the Canon ministering over a ceremony of multiple burials at sea on board the ship was auctioned off. Wallace Hartley’s body, discovered fully dressed with his music case strapped to his body, was transferred to the Arabic and returned to England, where he was buried on 18 May in Keighley Road Cemetery, Colne, Lancashire. The crew saved and stored the bodies of an approximately two-year-old male infant, a third-class passenger, and the fourth body recovered. (Unknown Child)

Mission Completed – After a seven-day recovery operation, the Mackay-Bennett had:

- Recovered 306 of the 328 bodies found from among the 1,517 who perished aboard Titanic

- Buried 116 at sea, of which only 56 were identified

- Set sail for home with 190 bodies on board, almost twice as many as there were coffins available

- Arrived in Halifax on 30 April 1912, began unloading her cargo at 09:30, and transferred the bodies to the ice rink of the Mayflower Curling Club

The crew split the $100,000 reward for Astor’s body (approximately $2,500 each). They used some of the money to pay for the burial of the unknown child’s body and his headstone monument – the casket was marked by a copper plaque reading “Our Babe.” On May 4, 1912, the entire ship’s crew, as well as the majority of Halifax’s population, attended the child’s burial at Fairview Lawn Cemetery. On July 30, 2007, Lakehead University researchers announced that testing of the body’s mitochondrial DNA had revealed that the child was 19-month-old Sidney Leslie Goodwin.

In May 1922, the ship was retired and anchored in Plymouth Sound to be used as a storage hulk. During World War II’s Blitz on England, she was sunk by a Nazi Germany Luftwaffe attack but later refloated. In 1965, her hulk was finally scrapped.

For Those Interested Amazon Prime has a Documentary on “Titanic: The Aftermath“