Most of us have seen images of sea turtles malformed by plastic six-pack rings, dead birds with stomachs full of debris, animals smothered by plastic bags…

Our excessive use of disposable plastics is disastrous, not just for wildlife, but for us as well. Canada is starting to take it seriously, with a ban on several single-use plastic items starting in December.

Manufacturing and importing plastic bags, takeout containers, single-use plastic straws, stir sticks, cutlery and six-pack rings will banned by December, sales by the end of next year and exports by the end of 2025. The goal is to keep “15.5 billion plastic grocery bags, 4.5 billion pieces of plastic cutlery, three billion stir sticks, 5.8 billion straws, 183 million six-pack rings and 805 million takeout containers” from littering lands and waters and ending up in landfills every year. (There’s an exception to the straw ban for people who require them for medical or accessibility reasons.)

Although the timeline seems long and the list of items short, government faced enormous pressure from industry, including legal battles. Plastics companies and organizations have challenged the government over jurisdiction, arguing regulation should be left to provinces, and over scientific assessments and classification of plastic manufactured items as “toxic.”

Almost all plastic is a byproduct of the oil industry, which has also pushed back. For example, Imperial Oil filed a notice of objection to the government’s classifying plastics as “toxic substances” under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act.

The restaurant industry and the provinces of Ontario, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Quebec have also pushed back against regulations.

But given the excessive amounts of plastic choking lands, rivers, wetlands, lakes, oceans and even air, industry should work to get ahead of the ban, phasing out the six targeted items and other non-essential plastics sooner rather than later. And the public and governments must get behind the call to expand the ban to more items. Public pressure has already helped, with the ban on exports — originally exempted — added since last December.

The government is starting with the most common and harmful items but isn’t ruling out banning other single-use plastic products. That’s important because those banned make up only about five per cent of Canada’s plastic waste.

Recycling is only a partial solution as less than 10 per cent of plastic waste in Canada is recycled, with 3.3 million tonnes, much of it packaging, thrown out annually, according to the CBC.

With the ban, Canada is catching up to other countries. France banned most of the items last year, and is now phasing in further bans on items such as packaging on fruits, vegetables and newspapers, plastic in tea bags and toys handed out with fast food meals.

Making bans work requires education and ensuring sustainable options are available when needed. Because the ban is limited, it will also mean preventing companies from switching to alternatives that are no better, such as shrink wrap instead of drink container rings.

The greatest challenge is from industry. As the oil industry faces rising concerns about pollution, climate disruption and global instability, it’s been looking to plastics to increase demand. Oil giant BP has predicted plastics will represent 95 per cent of the net growth in oil demand between 2020 and 2040. Because of increasing restrictions and public pressure in the industrialized world, the plans hinge on pushing plastics in places like Africa.

As well as being a major pollution source, plastic is fuelling the climate crisis. Carbon dioxide emissions are produced at every stage of its life cycle, averaging about five tonnes of CO2 per tonne of plastic — more if it’s burned. According to a Vox article, “That’s roughly twice the CO2 produced by a tonne of oil.”

Plastics can be useful, especially in medical and public health settings — although alternatives are increasing. But most of the plastic we use and throw away is unnecessary. Just as we must stop using fossil fuels, we must also move away from their plastic byproducts. Canada’s ban is a good start, but we need to go further, and faster. It’s one area where our personal choices can make a big difference. New government standards make that easier. There’s no future in plastics.

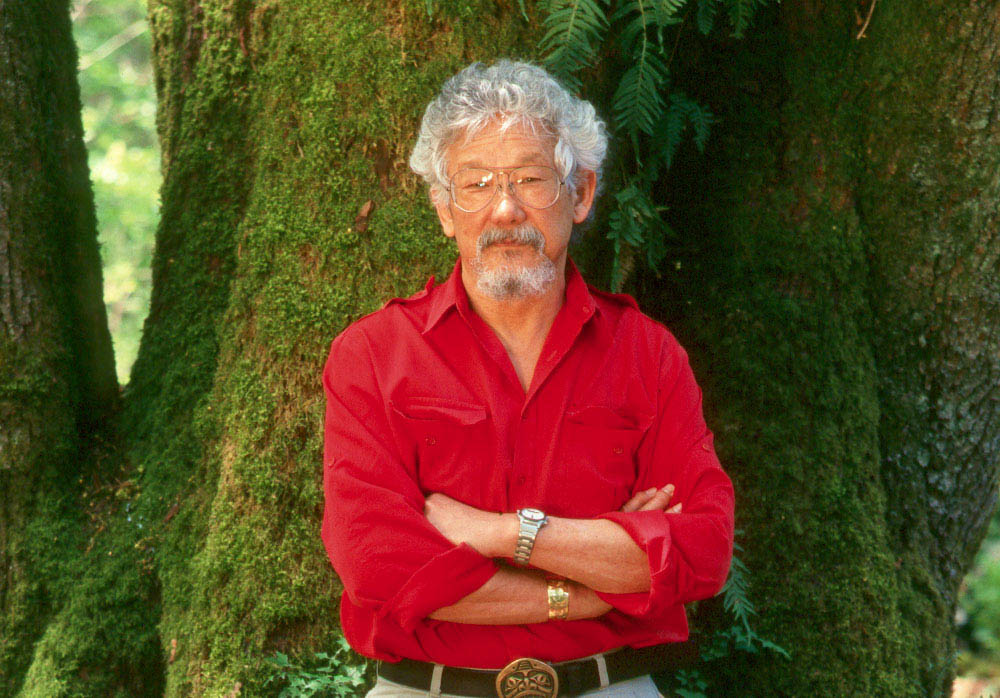

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Senior Writer and Editor Ian Hanington.