Beavers have long been considered nuisances. They knock down trees and block waterways, often flooding areas where humans live and gather. But recent moves to leave the beavers alone show they can enhance and restore natural environments.

Like other animals that create, modify and maintain their environments, beavers are referred to as “ecosystem engineers.” In one study, scientists determined busy beavers improve ecosystem health, “increasing species richness at the landscape scale.” They found that in New York’s central Adirondacks, “ecosystem engineering by beaver leads to the formation of extensive wetland habitat capable of supporting herbaceous plant species not found elsewhere in the riparian zone.”

In Europe, many towns and municipalities are reintroducing beavers where they were previously wiped out. In Scotland, beavers were released into a 44-square-kilometre area in 2009 after a 400-year absence. The five-year trial’s success convinced the government to allow beavers to remain.

According to Wildlife Trusts, an organization instrumental in European rewildling efforts, beavers and the landscapes they generate benefit people and wildlife by helping to reduce downstream flooding — “the channels, dams and wetland habitats that beavers create hold back water and release it more slowly after heavy rain.” They also reduce siltation, and the wetlands sequester carbon, an essential process for fighting the climate crisis.

In Vancouver, where I live, beavers in Stanley Park have created new wetland habitat and reduced invasive species like water lilies. (Some human intervention has been necessary, such as protecting a number of trees with wire mesh, and taking measures to ensure water levels are maintained.)

Beavers aren’t the only animals that engineer the worlds around them, often making them more viable for other creatures. Many do, which has led to efforts worldwide to reintroduce species to fulfil the roles they’ve historically played in maintaining healthy ecosystems. In fact, one could argue that all animals play an active role in shaping the places in which they live, to varying degrees. Some, such as invasive zebra mussels, can negatively reshape ecosystems. (The human animal, of course, has engineered some of the worst impacts!)

According to Janet Marinelli in Yale Environment 360, “In the past two or three decades, research has underscored the importance of large mammals like bison as ecosystem engineers, shaping and maintaining natural processes and sequestering large amounts of carbon.” She notes that bison wallowing sculpts “depressions in the ground where water can accumulate and sustain healthy stands of grass.”

Marinelli also writes, “coral-reef habitats, created by the ecosystem engineer coral species, hold some of the highest abundances of aquatic species in the world,” and, “Prairie dogs are another terrestrial form of allogenic ecosystem engineers due to the fact that the species has the ability to perform substantial modifications by burrowing and turning soil.” Their activity influences “soils and vegetation of the landscape while providing underground corridors for arthropods, avians, other small mammals, and reptiles.”

Similarly, marine vegetation such as eelgrass is an anchor for healthy marine ecosystems, as seagrasses create and modify structural elements of the sea. As scientist Sarah Berke points out, “structures in marine habitats play myriad well-documented roles, providing living space for other organisms and refugia from predation, increasing heterogeneity, altering hydrodynamic regimes, and altering deposition of sediments and larvae.” A David Suzuki Foundation study found that shoreline and eelgrass planting and beach nourishment can substantially reduce erosion and create other benefits for people and wildlife habitat.

Engineering can take many different forms. The most obvious is structural engineering, in which creatures create or modify elements of their habitat. But, as Berke notes, engineers also modify chemical environments and even the levels of light entering a land or seascape. “In modifying light, plankton and filter feeders are analogous to those terrestrial organisms that cast shade, most if not all of which are structural engineers. In terrestrial systems, then, light engineering entirely overlaps with structural engineering, while in marine systems light is largely controlled by organisms that do not create structure.”

Ultimately, when we lose wildlife populations, we don’t only lose the animals themselves; we also lose the version of the world that was shaped, in part, by their agency. The result, like so many of our impacts, is less healthy, more monocultured ecosystems that reflect back only human enterprise.

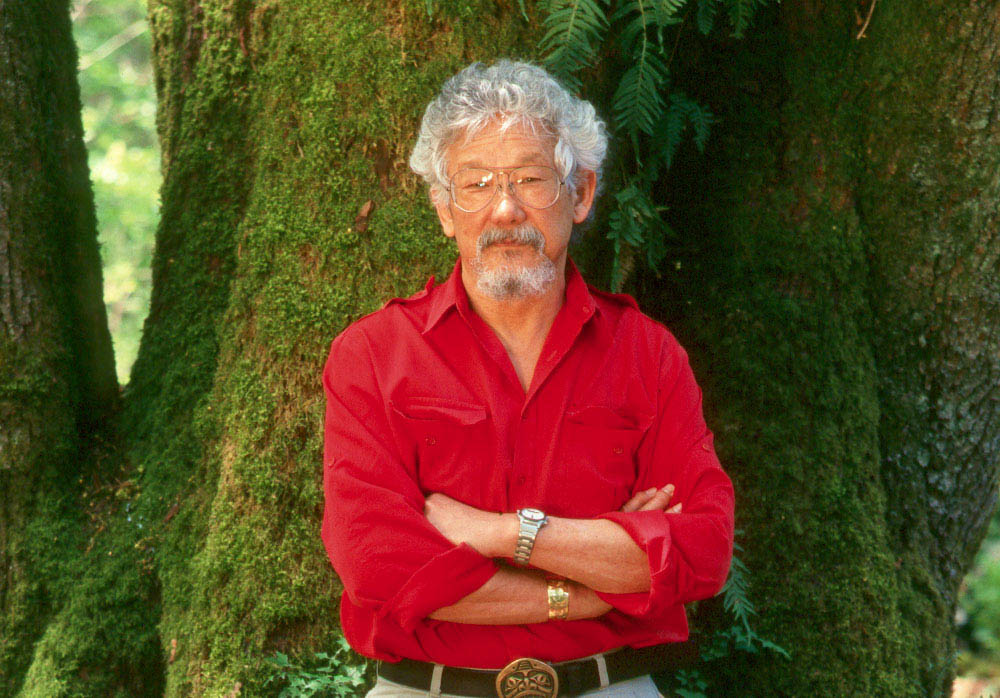

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation. Written with contributions from David Suzuki Foundation Boreal Project Manager Rachel Plotkin.