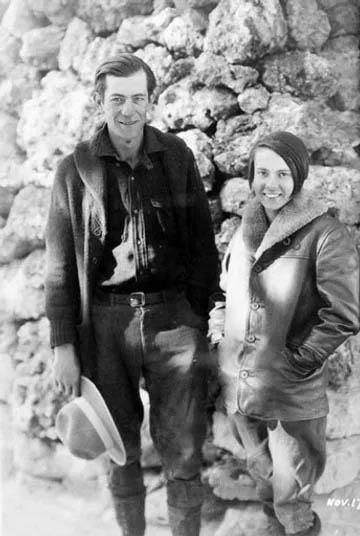

Glenn and Bessie Hyde left Emery Kolb’s house near the Bright Angel Trail of the Grand Canyon on November 18th, 1928, and began walking back towards the Colorado River.

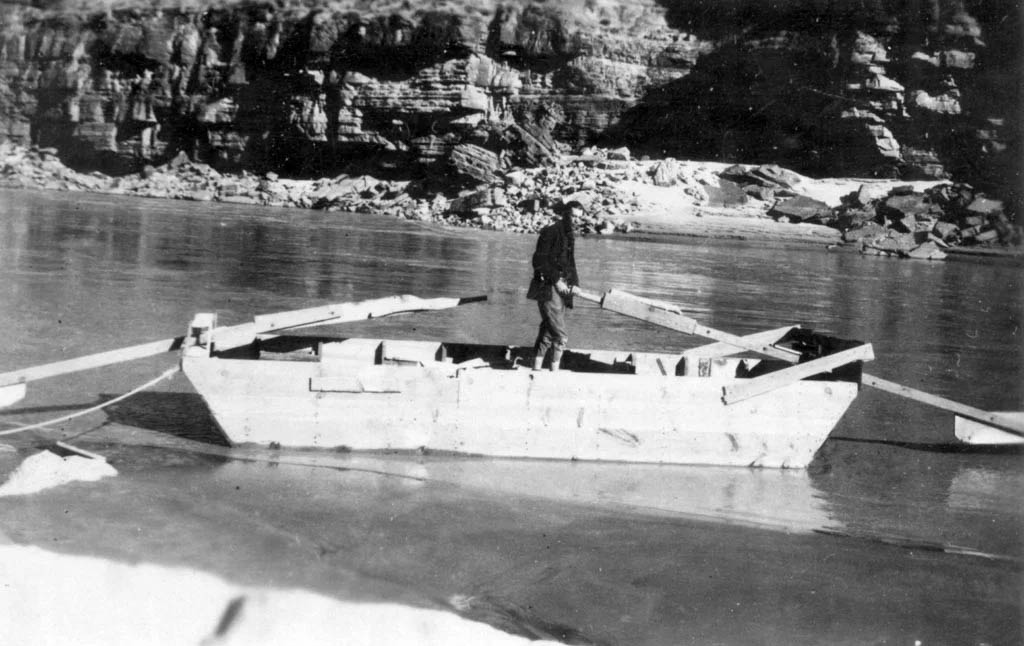

The Hydes had tied their boat up on the nearby shoreline — a homemade scow named Rain-in-the-Face they’d spent weeks living aboard as they floated down the Colorado River on their honeymoon. The adventurous couple were aiming to set a speed record for navigating the Grand Canyon by water. If they were successful, Bessie would also be the first woman to boat the entire length of the almighty canyon.

According to The Adventure Journal, before heading leaving the Hyde’s, young Bessie looked back at Emery Kolb’s youngest daughter and admired her adorable outfit, saying aloud, “I wonder if I shall ever wear pretty shoes again.” With that, Bessie and Glenn turned the corner and headed back to the Colorado River.

They were never seen again.

Their scow, a flat-bottomed river boat built by Glenn over the previous year, was found three weeks later. It was in working order, still floating in the river, with no one aboard and no signs of foul play. The boat was not battered by the rocky shoreline and showed no evidence of having flipped over – a clear indication that the young couple hadn’t encountered dangerous waters in recent days. All their food and personal possessions were still aboard.

There was no indication the Hydes had abandoned their vessel, and there was no sign of them on the nearby riverbank.

Glenn was a seasoned boater, having already completed arduous trips like the Salmon River and Snake River in Idaho. Bessie was less experienced, but still had spent time in dangerous waters, mostly with Glenn, and the couple had spent ample time preparing for the trip.

At the time of their visit with the Kolb’s, they were already halfway through their journey. They began on October 20th on the Green River in Utah and were set to finish in Needles, California.

In the Adventure Journal expose and other retellings, it was reported that Kolb felt Bessie may have become weary of the dangerous waterway — perhaps increasingly fearful as they approached some of the most dangerous portions in the Canyon. But with nothing but hearsay and local gossip filling the news, local police were confounded. By all accounts, Glenn and Bessie had left the Kolbs in good order, seeking to maintain their ambitious schedule. There was no definitive proof anything was amiss.

After no word from the Hydes for several weeks, Emery Kolb began a search in mid-December. With the help of an airplane, the Hydes boat was found near Mile 237 on the Colorado River on December 20th. The last entry in Bessie’s diary, which was still safely stored inside the boat, was from November 30th. It indicated their last position was near an area known as Diamond Creek. The bowline from the Hydes boat was caught on something below the surface, which had kept it in place for an unknown length of time. For reasons unknown, Emery Kolb cut the bowline and freed the boat, something for which he was greatly criticized later.

Searchers backtracked from Mile 237 to Diamond Creek to search for the couple. They spent more than a month combing the canyons around Diamond Creek, but found nothing. The Hydes were gone.

This is where the story of the Hydes disappearance and urban legend intersect.

With no satisfactory conclusion to Glenn and Bessie’s disappearance, local rumours began to flourish.

Had the Hydes been murdered? Or were they simply victims of big water and bad luck?

It was true that Emery Kolb had begged the Hydes to take life jackets when they left his home on November 18th. He’d discovered Glenn didn’t have any aboard, and despite asking him to take some of his own for the remainder of the trip, Glenn had laughed off his concerns.

Had there been a lover’s quarrel between the newlyweds? Had Bessie’s unhappiness about the trip boiled over and she lashed out at Glen? Had Glen become disenchanted with his wife’s faltering enthusiasm for his adventure?

No one knows.

The rumours reached such a fever pitch they were even covered by the L.A. Times. Then in 1971, a woman on a commercial boating trip claimed to be Bessie Hyde. She told fellow passengers she’d stabbed Glen in a fit of rage. From there, she’d hiked out to Peach Springs, Arizona and started a new life. When tracked down by reporters, the woman, named Elizabeth Cutler, denied ever having made the statement to her tripmates despite several statements claiming that she did.

Another shocking detail emerged after the passing of legendary Grand Canyon river guide Georgie Clarke in 1992. Among her possessions was a pistol, the Hyde’s marriage certificate, and a birth certificate listing Clarke’s real name as Bessie DeRoss. Was she in fact Bessie Hyde? To have the Hyde’s marriage certificate was beyond strange, but despite the discovery local authorities did not reopen the case.

But the most intriguing detail to emerge since the Hyde’s disappearance came from Emery Kolb himself. After his passing in late 1976, Kolb’s garage was cleared out by his estate in early 1977. Inside they found a human skull with an obvious bullet hole. An initial examination determined that the skull belonged to a man in his 20’s who was roughly the same height and build as Glen. This sent the rumour mill ablaze. It wasn’t until 2008 when a forensic analysis determined it was not the skull of Glen Hyde. Furthermore, good detective work uncovered that Kolb had served as a county coroner jury representative for Grand Canyon and had likely kept the skull from a different case after it’s inquest.

So, what became of Glen and Bessie? And what became of their boat, the Rain-in-the-Face? The remains or Glen & Bessie Hyde have never been found, nor has any new evidence emerged that might suggest their wherabouts or what occurred on that fateful day in November 1928. As for their boat, by all accounts after Emery Kolb cut it loose near Mile 237, it floated downriver until the waterway swallowed it. Who knows what evidence might have remained onboard, and questions still persist as to why Kolb felt it necessary to cut the boat free.

The legend of the Hyde’s boat still persists among those who live around Diamond Creek.