As the new guardian of the Oliver Mowat, Kayla Martin makes good on a promise to survey and document this once-secret wreck and make it available to all divers

The lake was as still as glass as I led team members Charlotte Pilon-McCullough and Jill Heinerth down the shot line, which was disappearing into the darkness below. It felt like I was sinking forever when a cold shiver ran down my spine thinking about that fateful accident that led to this moment.

That night

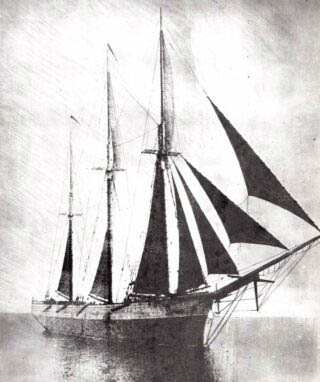

September 1, 1921, was a clear moonless night as Captain Van Dusen manned the helm of the Oliver Mowat sailing from Picton, Ontario, to Oswego, New York. Near midnight, lights appeared out of the east from a large steamer heading directly toward his ship. Using an oil lantern, Dusen attempted to signal their position and warn the oncoming vessel away.

Onboard the Steamer Key West, the Captain was off duty while the second mate was on the bridge recording the day’s events in the ship’s logbook. With calm winds on this quiet night, the lookout left his post to light a fire in the galley to prepare coffee for the long night ahead.

At 10:57 pm, the fate of the Oliver Mowat was sealed as two thousand tons of steel struck her amidship, driving a wall of water into her heart, and sending the schooner to the bottom in just four minutes. The Captain made a heroic attempt to save his crew of five, but in the end, he went down with his ship along with the first mate and cook. The remaining two sailors were pulled from the icy waters and survived to tell the tale.

As I continued my descent, a shape began to take shape in the gloom, and the ship’s wheel appeared before me. The vessel was breathtaking and lived up to the tales I had been told by the four shipwreck hunters that found her position in June of 1996. Since then, the wreck has been kept secret, and only a few have had the privilege of diving on her.

New guardian

Last fall, with the passing of Rick Neilson, the remaining hunters, Barbara Carson, Spencer Shoniker and Tim Legate, decided that the Oliver Mowat belongs to Canada and the public, so they chose me as its guardian. They would only pass on guardianship if I promised to ensure that the wreck was surveyed, documented, and had a proper mooring buoy. With funding from the Royal Canadian Geographical Society and the support of the Ontario Marine Heritage Committee and Save Ontario Shipwrecks, I mounted this expedition to tell her tale, documenting the wreck through video and stills and completing an archaeological survey that will help with placement of a permanent marker buoy on the site.

Glancing at my dive computers, I noticed we were 121 feet (37m) down and knew our time limit would be fourteen minutes. With time being of the essence, we each proceeded to our assigned tasks. While Jill captured images, Charlotte and I surveyed the site, heading towards the bow 130 feet (40m) away.

All three masts were broken, the mizzenmast and mainmast were lying to starboard, and the foremast was to port with the crow’s nest still intact. Passing up the portside, I was stunned by the size of the hole in the hull where the Key West had collided with her. I could understand how a schooner this large could sink so fast.

The wreck was picture-perfect, sitting upright; it was hard to believe that it had been resting on the bottom for over a century. Gliding across her deck allowed me to slip back in time, and for a moment, it felt like I was part of the crew during the golden age of Great Lakes Schooners.

Documenting and sharing

With visibility at an exceptional 100 feet (30m), capturing images was the goal of the dive, particularly the two most breathtaking features, the bowsprit and the wheel. The foremast fife rail was still intact, including a belaying pin. Fife rails circle the bottom of the masts and are usually destroyed when the masts are broken. Deadeyes were lining the rails; they would have been used to secure the rigging that held the masts upright. Near the spectacular bow was a coal-fired donkey boiler that would have generated steam to power a winch to assist the crew.

Shipwrecks are underwater museums and cultural heritage sites. They are vital to understanding and preserving our past. One of the expedition’s goals is to have a mooring system placed to protect the wreck from being damaged by people hooking onto the wreck. Once an archeological survey and photogrammetry of the wreck are complete, the plan is to release the coordinates to the diving community, as this wreck belongs to all of us. These conditions are being completed at the request of the original hunters as we share the goal of protecting wrecks from harm while ensuring the safety of the diving community.

Diving on the Oliver Mowat is like looking into the past. It is a treasure trove of life in a different period. We feel very humbled swimming down the length of her graceful curves, and I think of how privileged we are to enjoy her beauty again.

As our bottom time was quickly running out, we reluctantly left the wreck. Looking down as we slowly ascended, the Oliver Mowat was swallowed up by the darkness and would be hidden from sight until the next time that we could return to uncover more of her secrets.

Article written and submitted by Kayla Martin

Photography by Jill Heinerth and Durrell Martin