Considering all the information on the internet, you’d think people would be better informed and able to assess the forces that affect our lives. That’s clearly not the case. Many scroll through websites and information outlets until they find sources — complete with “authorities” touting PhDs or MDs — that confirm their biases, opinions or hunches.

A simple search of “creationism,” “vaccine safety” or “climate change” generates dozens of sources claiming to prove or debunk various claims. Why consider alternatives when it’s so easy to find corroboration of entrenched beliefs? Labelling people and ideas one disagrees with as “fake,” “hoax” or “political” further reinforces positions. Scientists are falsely accused of promoting causes out of self-interest to get bigger grants or influence politicians.

It’s not a new problem. When I began to host TV programs, I wanted to provide insights that would encourage viewers to take science seriously and learn about what was going on in different fields. You don’t have to be academically trained to understand some of the basic concepts that shape the world and respect what scientists say. At the same time, scientists have a reciprocal responsibility to make their ideas and research accessible to a lay audience.

But as with today’s internet, television was and still is mainly for entertainment. TV was often denigrated as the “boob tube.” People seldom watch to be educated or enlightened. We watch in a desultory way rather than concentrating as we might do in a classroom. Things distract us — a child may need attention, we may want a drink or need to go to the bathroom.

Not everyone “gets” science. But if those we elect to make tough decisions about the world can’t or won’t find or assess accurate information or take the best scientific advice, the consequences can be death and devastation.

During an inquiry into the U.K. government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, Patrick Vallance, a medical doctor and the government’s chief scientific adviser, reported that then-Prime Minister Boris Johnson “at times struggled to follow basic scientific concepts crucial to Covid such as the impacts of lockdown on waves of infection, and had to have them explained repeatedly.”

Asked whether Johnson understood the science, Vallance pointed out that Johnson’s most recent science course was when he was 15 and that he admitted science was “not his forte.” Vallance added, “It was hard work sometimes to try and make sure that he had understood what a particular graph or piece of data was saying.” Johnson was “bamboozled” by modelling “and would fail to understand ideas put to him.”

Johnson and then-Chancellor (now PM) Rishi Sunak, fearing a public backlash, were reluctant to impose a second lockdown, and believed most who died were old. Johnson favoured “letting it rip” saying, “Yes, there will be more casualties, but so be it; they have had a good innings.” (An “innings” refers to the time a cricket player is up to bat.) Sunak thought it was okay to just accept that some people would die. He was reported to have said a COVID strategy was “all about handling the scientists, not handling the virus.”

Vallance recalled a phone call to scientific advisers in other countries. When one said their leader could not understand exponential curves, “the entire phone call burst into laughter because it was true in every country.”

As president of the United States, Donald Trump endorsed the horse dewormer ivermectin to treat COVID and initially dismissed the virus as a hoax (along with climate change). Under Stephen Harper, Canada’s government refused to address human-caused climate change as a real threat and dismissed proposals to reduce emissions as “crazy economic policy.” Alberta’s government won’t discuss climate change as a serious problem created by fossil fuel use.

Scientifically illiterate political leaders are hazardous. Issues like climate change, pandemics, plastic pollution, artificial intelligence, ocean acidification, species extinction, deforestation and numerous others need big decisions and policies. How will we make proper decisions if we don’t base them on the best scientific information? So-called leaders, lacking any grounding in science that would enable them to assess the reams of graphs, curves and data, are making decisions based on ideology and personal beliefs. That’s terrifying for an animal that boasts of intelligence.

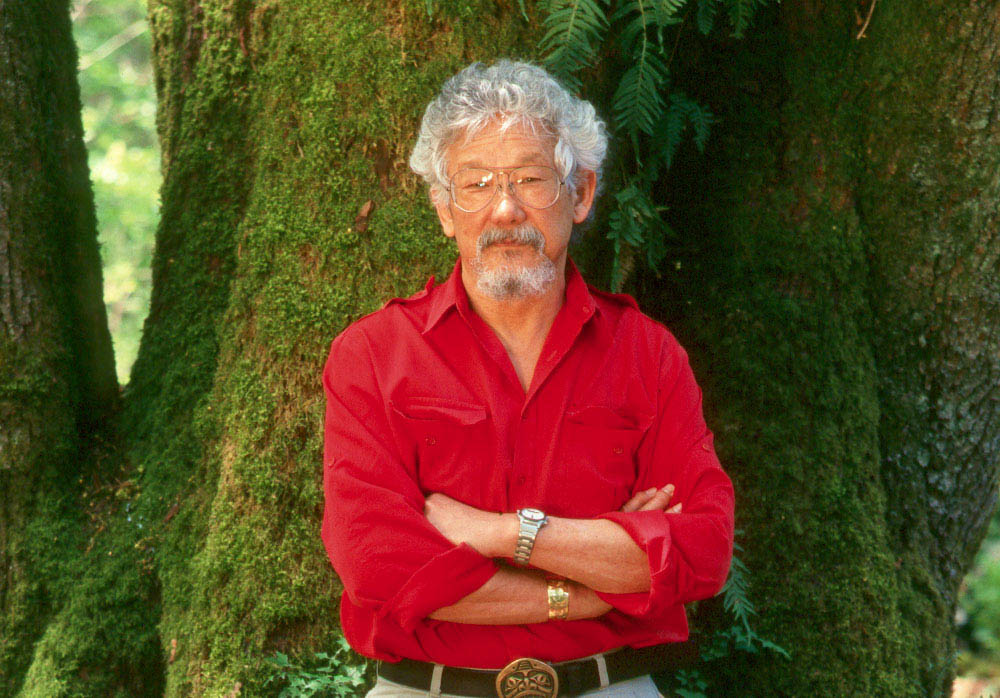

David Suzuki is a scientist, broadcaster, author and co-founder of the David Suzuki Foundation.

Learn more at davidsuzuki.org.