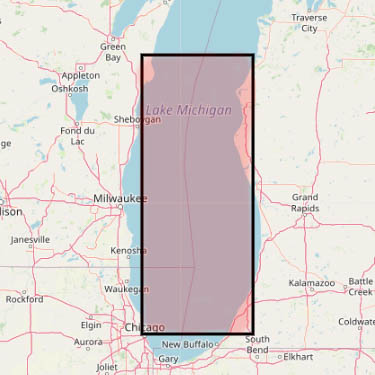

The Lake Michigan Triangle, sometimes known as the Michigan Triangle, is a region in Lake Michigan where several plane crashes, shipwrecks, and disappearances have happened for unknown reasons. There have also reportedly been reports of unidentified flying objects (UFOs) and unexplained submerged objects (USOs) seen nearby. The triangle is made up of Ludington, Manitowoc, Benton Harbour, and Ludington again. The loss of the French sailing ship Le Griffon and her crew in the 17th century marked the beginning of a significant unexplained occurrence. beginning with the Thomas Hume ship’s sinking Shipwrecks and missing persons cases increased in frequency in 1891. In 1913, there was the first known sighting of a UFO.

Jay Gourley initially addressed the frequency of disappearances, shipwrecks, and plane disasters inside the Great Lakes in his 1977 book, The Great Lakes Triangle. Subsequent writers concentrated on events in Lake Michigan, especially those that occurred inside the Michigan Triangle, even if the exact genesis of the triangle is unknown.

Experts have disagreed over the triangle’s range and form. Some have contended that the region, encompassing most or all of Lake Michigan, is not a triangle but rather an oblong or rectangular shape.

The triangle is a fiction, according to the Lake Michigan Shipwreck Research Association, which asserts that there are no more shipwrecks in the triangle than there are throughout the other Great Lakes. They added that there are a lot of shipwrecks in the Great Lakes because of the heavy traffic that passes over them.

Explanation Attempts: Natural

Wind waves have been held responsible for a large number of shipwrecks and ship disappearances in Lake Michigan. The lake’s elongated shape and location cause its sides to be parallel and unhindered, which promotes the production of hazardous currents such longshore tides and riptides. Furthermore, waves can reach enormous heights due to consistent wind patterns and the north-south orientation.

Magnetic abnormalities brought on by magnetic declination and magnetic deviation are another widely accepted explanation for the disappearances. The location-dependent discrepancy between magnetic and true north is referred to as declination. Lake Michigan swings four to five degrees to the west on average. Deviations are mistakes brought on by nearby magnetic fields in compasses. The compass needle would point in the direction of the magnetic item rather than magnetic north, for instance, if you were to hold it close to one. This might confuse new pilots and sailors, even though it wouldn’t be an issue in cars with other navigational aids.

Explanation Attempts: Paranormal

The triangle has been attributed by conspiracy theorists to a negative energy vortex. The concept of energy vortexes holds that particular places release transformative, strong, and sacred energy. It’s said that there are vortexes containing negative energy in addition to the positive ones, which are generally thought to encourage healing and positivity. These are supposedly dangerous and malevolent places. Energy vortex sources are frequently identified as ley lines, which are regions where historic buildings and sites converge. Ley line maps show that one passes through the centre of Lake Michigan. Others link the triangle’s purported vortex to a prehistoric building excavated beneath Lake Michigan that investigators found in 2007. It’s common to refer to the location as “North American Stonehenge”. Some assert that UFO sightings are proof positive that aliens are to blame for the happenings in the Lake Michigan Triangle.

Notable Incidents

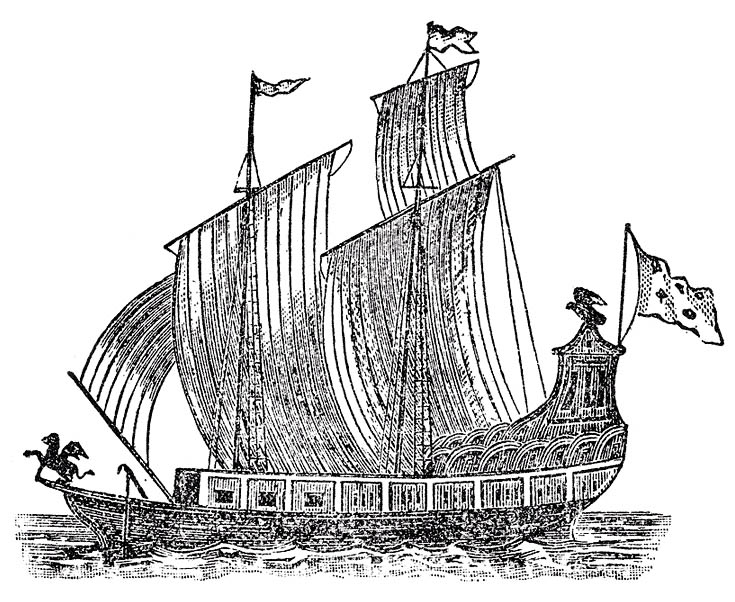

Le Griffon

The disappearance of the sailing ship Le Griffon and her crew on September 18, 1679, is one of the first instances related to the Lake Michigan Triangle. After mooring at La Grand Baie, which is now Green Bay, Le Griffon loaded 1,2,000 pounds (5,400 kg) of fur and sailed for Lake Erie. Nevertheless, the ship never made it to her intended location, and no verified ship parts have ever been found. There are many who believe Le Griffon died in a storm. Some have speculated that she was boarded by the Ottawas or Pottawatomies, who killed her crew before setting her on fire. The ship’s builder, Sieur de La Salle, René-Robert Cavelier, was certain that the pilot and crew had sunk the vessel and fled with the fur. There isn’t any substantial evidence for this theory.

Thomas Hume

The schooners Thomas Hume and Rouse Simmons left the port on May 21, 1891, having dropped a load of lumber in Chicago. The crew of the Rouse Simmons left the two ships in Chicago until the weather cleared up, even though both were meant to return to the Hackley-Hume Lumber factory in Muskegon. The six sailors on board the Thomas Hume, however, vanished as the ship went on. Although Hackley-Hume offered a $300 reward and dispatched a ship to look for the schooner, they were unable to locate the ship. Numerous theories emerged regarding the fate of the Thomas Hume, with the most commonly recognized theory positing that she capsized due to the same storm that forced the Rouse Simmons to withdraw to Chicago. Others, including Charles Hackley, believed that another boat collided with and sunk the schooner.

The sinking ship was found in 2006 by an A & T Recovery employee who was looking for a lost US Navy aircraft. It was 150 feet (46 meters) below the surface, in chilly water, when she was discovered nearly entirely whole. The Michigan Shipwreck Research Association declared that the Thomas Hume was too intact to have been struck by another ship and came to the conclusion that she had perished in a storm.

Rosabelle

A two-masted schooner named Rosabelle was utilized to deliver supplies to the House of David in Benton Harbour. She was discovered capsized twice on Lake Michigan between 1875 and 1926, with no indications of her crews.

The schooner was found drifting upside down in 1875 while being crossed by a vehicle ferry across the lake. The boat’s ten-man crew was never located after they left. After that, the ship was turned over and brought back to Milwaukee, where it was kept in operation.

The ship was prepared to sail once more in October 1921, this time carrying lumber made of maple and potatoes. Ed Johnson, the ship’s captain, declined to board the schooner, nevertheless. Johnson, according to his son, had a premonition that something terrible was going to happen. Johnson was not persuaded by the crew to board the Rosabelle once more, so they departed without him. When the ship was discovered capsized a few days later, the crew had vanished from sight. There was a collision since the stern was missing, but no ship reported an accident. After dragging the schooner into Racine Harbour, the US Coast Guard subsequently concluded that there had not been a collision.

George R. Donner

The skipper of the coal freighter O.M. McFarland was George R. Donner. On April 28, 1937, Donner’s 58th birthday, the ship sailed west through the lakes to Port Washington, Wisconsin, after loading 9,800 tons of coal in Erie, Pennsylvania. The skipper had guided the O.M. McFarland through ice floes for hours on the bridge. Once they were in Lake Michigan, Donner went to his stateroom and gave the crew orders to notify him as soon as the ship got closer to her target. When the ship approached Port Washington three hours later, the second mate went to Donner’s stateroom and discovered that it was locked from the inside. He proceeded to the galley, supposing Donner had gone there for a bite, but to no avail.

The crew immediately started a thorough but fruitless search for their captain. Eventually, they smashed through the cabin door, but Donner was nowhere to be seen. Donner didn’t exhibit any depressive symptoms or thoughts of suicide, and he was too big to fit through his room’s two portholes. Ships and local ports looked for Donner in the water, but they were never able to locate him.

Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 2501

Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 2501, which was carrying 55 passengers and three crew members, departed from New York City’s LaGuardia Airport for Minneapolis on June 23, 1950, in the evening. The crew was not overly concerned despite the fact that a preflight examination of the weather suggested thunderstorms and maybe squalls along the flight path. But Captain Robert Lind asked to descend to 4,000 feet instead of his allotted 6,000 feet in order to prevent turbulence. Lind made the same request as the plane reached Cleveland, Ohio, and this time it was granted.

In order to prevent a collision with the other aircraft, Lind complied with Air Traffic Control’s (ATC) instruction to drop to 3,500 feet after intense turbulence caused another plane to plummet 500 feet while flying over Lake Michigan. Afterwards, in an effort to escape storm activity, Lind and his copilot made the decision to turn south. But they happened to fly straight into a line of squalls. The plane sent out its final radio message at 11:13 p.m., asking to be allowed to drop below 2,500 feet. The crew probably requested the request in order to get a better view by descending below the clouds. But since there was another jet leaving Milwaukee at that moment, ATC refused to give them clearance.

Residents in the Benton Harbour and South Haven areas soon afterward reported hearing an aircraft flying low to the earth and then seeing a flash of light over the lake. A few witnesses claimed to have heard an explosion, however it was difficult to tell the sound from the clouds of thunder. Radio operators discovered the jet was missing by midnight. The Coast Guard found some wreckage and an oil slick the following day, around 18 miles (29 km) northwest of Benton Harbour. Over the next few days, the search turned up parts of upholstery, a seat armrest, and human remnants including hands, ears, and bones. There was also a pair of child’s pants discovered, which were subsequently recognized as belonging to traveller Chester Schaeffer, age 8. Because to the quantity of material washing up on the shore, officials had to temporarily close some beaches. However, a significant portion of the aircraft or its engines have never been found by searchers. The majority of the debris that was discovered was no bigger than a hand.

Authorities believe that Lake Michigan is where the plane crashed. Based on the evidence that was found, the plane most likely struck the sea at a high speed while travelling forward, downward, and to the left. It has never been established what caused the plane to crash. The most widely accepted theory is that it was caused by poor visibility and inclement weather for the pilots. Another opinion is that the plane exploded when lightning struck it. But there were no fire marks on any of the debris that was found. Because two local police officers noticed red lights hovering above the lake for two hours after the plane vanished, conspiracy theorists have claimed that the airliner was abducted by a UFO.

Don Schaller and Don Rodriguez

Donald Schaller piloted a two-seat Aero L-39 Albatros on July 3, 1998. Eastern European nations frequently deploy this high-performance, single-engine jet as a military trainer. The seasoned pilot Schaller intended to take part in his first air show at Traverse City, Michigan’s National Cherry Festival. Donovan Rodriguez, a flight teacher at Northwestern Michigan College since the 1970s, was seated in the passenger seat. Schaller radioed that he was 27 miles (43 km) from the Cherry Capital Airport, his departure point, and that he intended to return to the airport at around six o’clock in the evening. The jet disappeared from radar shortly after, and flight controllers could not get in touch with Schaller. Coast Guard helicopters swiftly started scouring the region, but discovered nothing. The next day, the Blue Angels’ C-130 “Fat Albert” and a Canadian transport jet joined the hunt. The search ended on July 9 after searching for clues over miles of land and sea.

The reason behind the disappearance remained a mystery. Though they are not clear what caused it, Michigan State Police believe the aircraft crashed into Lake Michigan. Both men were seasoned pilots, the weather was calm, and the aircraft was thought to be straightforward and dependable. In addition, the aircraft had ejector seats and parachutes, however it’s unclear if the seats worked. A jet flying overhead was heard by one witness, followed by a loud boom akin to fireworks. But he never did see a plane.

Sonar technology was used to perform an undersea search later that year. Searchers thought the 30-foot (9.1-meter) long object they found to be the plane. Divers verified that the object was in fact a rock formation the next year. Another sonar scan in 2008 found what may have been a plane around 140 meters (450 feet) below the surface. It was adjacent to a 1950s-era boat that sank. Since the diver was not trained to dive below 400 feet, a dive to determine whether the object was a plane could not be performed.