Disclaimer: I am not a medical professional. The information shared here is based on my personal experience and should not be considered medical advice. Always consult with a healthcare provider for medical advice and treatment.

Have you ever wondered how your earliest memories shape who you become?

One of my earliest memories is of sitting in my paddling pool in the garden on a scorching summer day, wearing my dad’s baggy wetsuit. I imagined myself on an underwater adventure, using my Action Man speedboat to push a frog across the pool (for which I’m sorry, if you look closely you can see his scared little face), pretending to discover all sorts of weird and wonderful creatures like Jacques Cousteau as I terrorised this poor little frog in my plastic circle of watery hell.

I was captivated by the idea of a space unconstrained by the rules of gravity and motion that bind us on the surface. I was also fascinated by how this space was shared with such alien-like and wonderful creatures that seemingly had no rhyme or reason for their shapes, colours, or behaviour. It was only a matter of time before I became a qualified diver and joined that world.

However, life often takes unexpected turns. At 27, I became very ill and was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes mellitus. The idea of diving died; at that point, I thought I might never be able to. It would simply be too dangerous. I wasn’t even sure what I could do on land let alone the sea. You feel let down by your own body; you feel like what you knew about it is unknown again. It’s unreliable, inconstant, and needs constant monitoring in fear of fatal consequences.

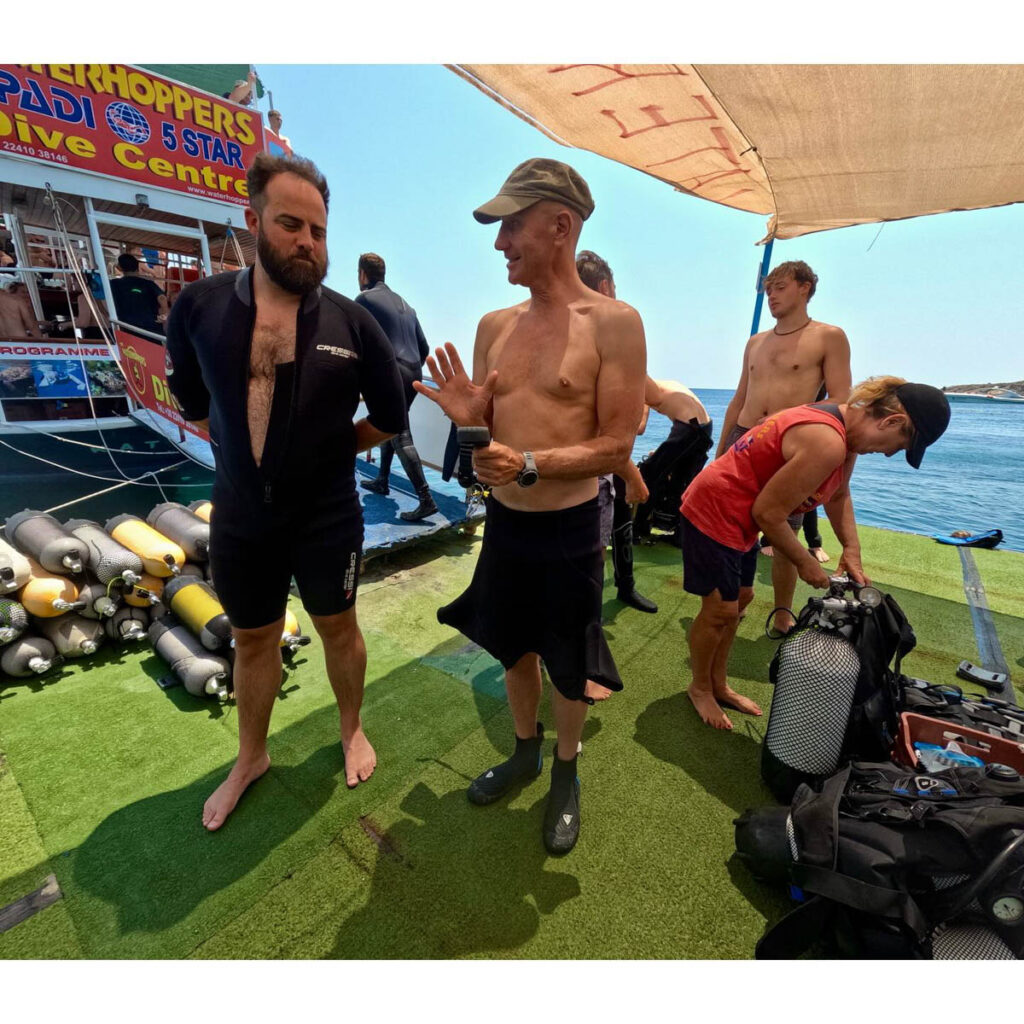

Years later however, now at 39, I just finished my PADI Advanced Open Water Diver certification course with WaterHoppers in Rhodes, Greece, but it wasn’t without its challenges. And that’s what I want to share with you my experience as a Type 1 diabetic diver.

What is Type 1 diabetes mellitus?

Type 1 diabetes causes the level of glucose (sugar) in your blood to become too high.

It happens when your body cannot produce a hormone called insulin, which controls blood glucose.

You need to take insulin every day, every meal to keep your blood glucose levels under control, insulin brings your blood glucose down and eating carbs, or sugar will bring it up.

Insulin can cause dangerously Low blood sugar (hypoglycaemia or a hypo) it is usually where your blood sugar (glucose) is below 4 mmol/L. It needs to be treated quickly to stop it getting worse, but you can usually treat it yourself. Some diabetics do not have hypo awareness, meaning they do not feel when they become too low – this can be very dangerous.

A Type 1 diabetic is always checking their blood sugar and adjusting it, much like constantly checking your air or using your Buoyancy Control Device (BCD) and breathing to float yourself up or down. If their blood sugar is too high, they will face many medical complications in the long run. If their blood sugar is too low, they could die or slip in to a coma.

What has been the case for Type 1 diving?

Historically, dive schools have often lacked the expertise or confidence to accommodate Type 1 diabetics, making them understandably hesitant. In exotic or remote locations, or even on offshore boats, medical assistance can be slow to arrive. However, the sport is becoming more accessible, with some schools now more willing to accommodate diabetics. Doctors are available, instructors are eager to learn and adapt, and advancements in medical technology, like the Libra or Dexcom sensors, have been game changers.

These sensors provide diabetics with much more information than the old finger prick test. Up until recently, a finger prick test only provided a single glucose reading at the time of the test. Imagine an SPG you had to connect to your tank while diving to get an air reading; then you disconnect it and carry on. Finger prick tests require multiple pricks throughout the day to track glucose levels. They don’t tell you where your blood glucose has been or where it is going. For example, your blood sugar might be crashing and falling really fast; in a few minutes, you are going to be in trouble, but a finger prick test won’t tell you this.

This is where the new continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are really useful. They continuously monitor glucose levels throughout the day and night. If your glucose levels go too low, an alarm will sound. If they go too high, an alarm will sound as well. More importantly, they can tell you if your blood glucose is stable and for how long it has been stable.

I don’t want to go hypo while diving, so whats the plan!?

I am nervous when I dive. Controlling diabetes is hard and can be unpredictable. However, for me, it was less about the issues I might face and more about whether I could be a good buddy. Would I be able to support my buddy and not be a burden myself?

To make sure I was prepared I visited my healthcare team to see if I was fit to dive, and gain advice to help me manage on dive day.

- Switched to slower insulin for diving; tested it before the dive (As my current method of delivery would not work at depth).

- Ate low-carb/zero carb breakfast to avoid blood glucose spikes; avoided fast-acting insulin.

- Maintained higher blood glucose levels before diving as a safety buffer.

- Carried hypo treatments: full-fat Coke, gummy bears, dextrose tablets.

- I made sure my instructor knew what to expect, what I was doing concerning my diabetic control on these dives.

Diving

People’s bodies react differently. It has never been the case for me that my blood sugar drops when doing intense training. I used to train for strongman competitions with extremely heavy weights, moving fast. Diving, for me, almost like clockwork, dropped my blood sugar whereas strongman wouldn’t make a single dent.

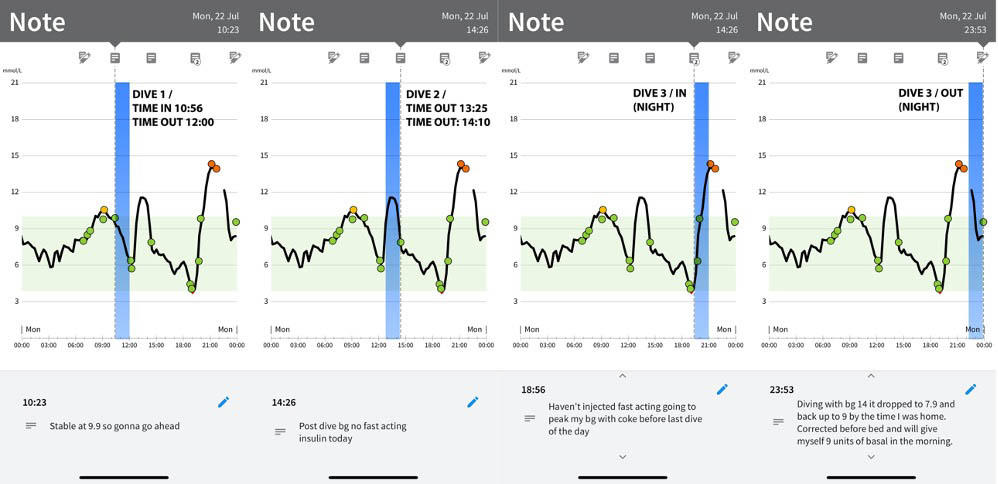

(Each dive is marked in blue)

I mapped my blood sugar before and after each dive to show you what happened to me while diving. This might not happen to you; in fact, this is unique to each individual. Each dive dropped my blood sugar by 5 mmol/L. I am so glad that I listened to my healthcare professional and maintained my blood sugar a little higher than usual to compensate.

Although diving presents a much harder challenge for a type 1 diabetic, it is manageable with a little planning, experimentation, and close monitoring, similar to checking your air or keeping your buoyancy in check.

I am so happy I took on this personal challenge and finally ventured into the water. This time, however, I won’t be terrorising any creatures I meet but will appreciate the opportunity to observe them safely.

I hope this article has been useful for only an insight to what a diabetic faces diving, keep safe.