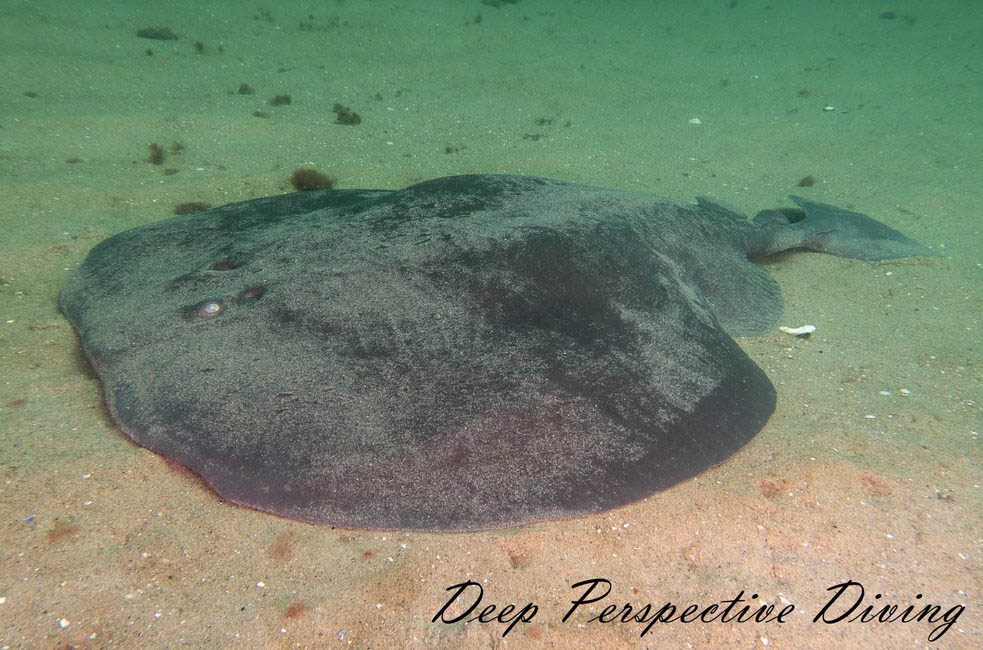

“A nice surprise at Paddy’s Head (Nova Scotia) this week. This Atlantic Torpedo Ray was spotted swimming past the reef balls at about 25 feet. These rays can deliver an electric shock up to 220 volts when hunting or being threatened. This one was easily 4 or 5 feet long. Such an impressive beast. I love the way they effortlessly glide through the water.“

Wayne T. Joy

Within the Torpedinidae family of electric rays is the Atlantic torpedo (Tetronarce nobiliana). At depths of up to 800 meters (2,600 feet), it can be found in the Atlantic Ocean, which stretches from Scotland to West Africa and off the coast of southern Africa in the east, and in the Mediterranean Sea. Adults are more often found in open water and are more pelagic in nature, whereas younger individuals typically live in shallower, sandy, or muddy environments. The Atlantic torpedo is the largest known electric ray, measuring up to 1.8 m (6 ft) in length and 90 kg (200 lb) in weight. It shares characteristics with other species in its genus, including a muscular tail and a big triangular caudal fin on an almost circular pectoral fin disc with a nearly straight leading border. Its two unequal-sized dorsal fins, smooth-rimmed spiracles (paired respiratory apertures behind the eyes), and uniform black colour are its distinguishing features.

The Atlantic torpedo is a solitary, nocturnal animal that can produce up to 220 volts of electricity to neutralize its prey or protect itself from attackers. Its primary food source is bony fish, although it also consumes tiny sharks and crustaceans. This species is aplacental viviparous, meaning that the developing embryos are fed by yolk and then get histotrophic (or “uterine milk”) from the mother. Females give birth to as many as sixty offspring after a year of gestation. This species can deliver an extremely painful and powerful electric shock, although it is not lethal. The Atlantic torpedo, which bears the name of the naval weapon, was utilized in medicine by the ancient Greeks and Romans due to its electrogenic qualities. Its liver oil has been utilized as fuel for lamps before the 19th century, but it is now worthless.

This species is classified as Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN); fishermen, both commercial and recreational, may inadvertently catch it, though it is unclear how this affects the population.

French scientist Charles Lucien Bonaparte gave the first scientific description of the Atlantic torpedo in his major work, Iconografia della Fauna Italica, in 1835. The syntypes were defined as sixteen specimens. The “great torpedo” of southern Africa is tentatively assigned to this species. T. nobiliana may potentially include another kind of electric ray discovered in the Indian Ocean near Mozambique. The Atlantic torpedo belongs to the genus Tetronarce. Its smooth-margined spiracles and relatively plain colouring set it apart from the other genus in the family Torpedinidae, Torpedo. Additional monikers that are frequently used are crampfish, electric ray, numbfish, black torpedo, Atlantic electric ray, and Atlantic New British torpedo.

The pectoral fin disc of the Atlantic torpedo is nearly round, 1.2 times wider than it is long, and has a thick, nearly straight front border. The eyes are tiny, and considerably larger spiracles that lack papillae on their inner rims follow. The nose and mouth are near to other; a skin flap with a curving back boundary separates them and is three times longer than it is wide. The mouth has noticeable grooves at the corners and is broad and curved. The number of these pointed teeth increases with age, from 38 rows in juveniles to 66 rows in adults. The teeth in the first few series are useful. The initial and fifth sets of gill slits are shorter than the rest.

The disc in the front barely overlaps the rounded pelvic fins. The initial dorsal fin emerges in advance of the pelvic fin insertions and is triangular in shape with a rounded apex. The distance between the dorsal fins is shorter than the length of the first dorsal fin base, and the second dorsal fin is only half to two thirds as large as the first. About one-third of the overall length is made up of the robust tail, which ends in a caudal fin with slightly convex edges that resembles an equilateral triangle. The skin is smooth and free of any dermal denticles, or scales. Dorsal coloration ranges from a simple dark brown to grey, occasionally with a few dispersed spots, and darkens towards the edges of the fins. The underside has black fin edges and is white. The Atlantic torpedo, the biggest of the electric rays, with a length of 1.8 meters (6 feet) and a weight of 90 kilograms (200 pounds). It is more common to have a length of 0.6–1.5 m (2.0–4.9 ft) and a weight of 30 lb (14 kg). Compared to men, females grow larger.

Similar to other torpedoes in its family, the Atlantic torpedo can launch a potent electric shock for both attack and defence from two kidney-shaped electric organs located in its disc. One-sixth of the ray’s weight is made up of these organs, which are made up of about half a million jelly-filled “electric plates” stacked in 1,025–1,083 vertical hexagonal columns on average (visible beneath the skin). When properly fueled and rested, a large Atlantic torpedo may generate up to a kilowatt of electricity at 170–220 volts thanks to these columns, which basically function as parallel batteries.The electric organ releases energy in a train, or sequence, of closely spaced pulses, each lasting about 0.03 seconds. Trains typically have 12 pulses, although records show that trains with over 100 pulses have occurred. Even in the absence of a clear external stimulation, the beam consistently generates pulses.

The Atlantic torpedo is a solitary fish that spends much of its daytime resting on or partially submerged in the bottom before becoming more active at night. Due to its size and strong defences against predators, it is rarely taken by other animals. The tapeworms Calyptrobothrium occidentale and C. minus, Grillotia microthrix, Monorygma sp., Phyllobothrium gracile, the monogeneans Amphibdella flabolineata and Amphibdelloides maccallumi, and the copepod Eudactylina rachelae are among the known parasites of the Atlantic torpedo. According to some reports, this ray could last up to a day without water.

The flatfish, salmon, eels, and mullet are among the bony fish that the Atlantic torpedo primarily eats, while it has also been observed to consume small catsharks and crustaceans. It has been reported that captive rays would lie motionless on the bottom and will “pouncing” on fish that pass in front of them. Upon making contact, the ray coils its pectoral fin disc around the victim, trapping it against its body or the bottom and delivering powerful electric shocks. With this tactic, the lethargic ray can snare reasonably swift fish. After being neutralized, the prey is brought to the mouth by the disc’s rippling motions and swallowed whole, headfirst. greater than its food intake.

The electric discharge from an Atlantic torpedo is quite strong and can be sufficient to render a person unconscious, even if it is rarely fatal. But what poses a bigger risk to divers is the confusion that comes after the shock. The flabby, bland meat of the Atlantic torpedo renders it unmarketable. Both commercial and recreational fisheries use bottom trawls and hook-and-line techniques to accidentally catch it. Usually, when captured at sea, it is thrown away or chopped up to use as bait.The Atlantic torpedo is classified as Least Concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN); nonetheless, there is a lack of precise information regarding capture rates and population trends. The species may be adversely affected by fishing mortality.

Throughout the classical era, some electric fish, such as the Atlantic torpedo, were employed in medicine. Roman physician Scribonius Largus described applying live “dark torpedo” to patients suffering from gout or persistent migraines in the first century of the common era. American inventor Robert Fulton first used the term “torpedo” to refer to bombs that submarines could attach to ships in 1800, but these early devices were more like current mines. As a result, the Atlantic torpedo gained the namesake for the naval weapon.