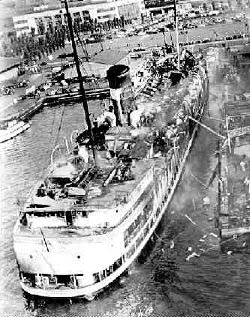

In September 1949, a fire in Toronto Harbour destroyed the Canadian passenger liner SS Noronic, resulting in the deaths of at least 118 people.

In 1910, the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) and the Northern Navigation Company, a division of the Richelieu and Ontario Navigation Company, entered into an operating agreement for the building of a new ship. Northern considered adding more cabins to the Huronic, albeit they did not immediately offer to build a new steamer at that time.

James Playfair, a shipping magnate, put up a bid to buy the Northern on behalf of himself and some partners in mid-January 1911. Regarding the prior operating agreement, the bid was pending GTR approval. Playfair made an offer to buy the business for C$1,250,000 plus C$1,000,000 in stock, subject to certain conditions. W. J. Sheppard, president of Northern, conveyed the offer to Charles Melville Hays, president of GTR, who then brought the issue up with his company’s freight and passenger departments. Hays asked Sheppard if he would think about whether the company’s future financial prospects would justify ordering a steamer to run alongside Hamonic that was of comparable capacity and similar style.

Due to Hays’ disapproval of the suggested ownership transfer, the Playfair agreement was not fulfilled. But Playfair set about trying to sway his views, and he succeeded in getting the GTR’s blessing. On February 6, Hays informed that Northern will furnish a new steamship within eighteen months as per the agreement with the two companies. The new ship, which would likely be 400 feet long, would be completed no later than 1913, when traffic would reopen. The unfortunate passing of Hays on the Titanic probably caused a delay in the commencement of work.

On June 2, 1913, the SS Noronic was launched at Port Arthur, Ontario. The Western Dry Dock and Shipbuilding Company constructed her for Canada Steamship Lines.

Designed to serve passengers and package freight on the Great Lakes, the Noronic boasted five decks, a length of 362 feet (110 meters), and a gross register tonnage of 6,095. She could accommodate 200 crew members and 600 passengers at full capacity. She was known as the “Queen of the Lakes” and was at the time one of the biggest and most exquisite passenger ships in Canada.

There were four passenger decks: A, B, C, and D. None of them had gangplank access directly to the dock. The lowest deck, the E deck, had the sole exits. Only two of the gangplanks—two on the port and two on the starboard sides—were in use at any given time.

City of Midland, Doric, Germanic, Ionic, Majestic, Waubic, Huronic, and Hamonic were the eight fleetmate ships of Noronic. Huronic was withdrawn and demolished in 1950, while Hamonic burnt in 1945.

From Detroit, Michigan, the United States, Noronic set out on a seven-day pleasure trip around Lake Ontario on September 14, 1949. She left Detroit and stopped in Cleveland, Ohio, to pick up more passengers. From Cleveland, she was supposed to go to Prescott, Ontario, and the Thousand Islands, and then back to Sarnia, where she was supposed to spend the winter. Noronic was transporting 171 crew members, all Canadian, and 524 passengers, all but twenty of whom were Americans.177 Captain William Taylor was in charge of the expedition. 179 On September 16, at 7:00 p.m., Noronic anchored for the night at Pier 9 in Toronto Harbour.

Passenger Don Church discovered smoke in the rear section of the starboard hallway on deck C about 2:30 in the morning. Church pursued the aroma of smoke until it led her to a small room off the port corridor, right in front of the women’s restroom. When he discovered that the smoke was coming from a locked linen closet, he reported the fire to bellhop Earnest O’Neil. O’Neil hurried to the steward’s office on deck D to get the closet keys without setting off the alarm. The fire swiftly spread throughout the corridor after the closet was unlocked, helped by the walls’ shiny wood panelling that looked like lemon oil.

Church, O’Neil, a different bellhop, and a passenger tried using fire extinguishers to put out the fire, but the flames forced them to retreat almost instantly. O’Neil was shocked to see that the fire extinguishers weren’t working. Church and his family abandoned ship as he hurried to his stateroom on deck D. In the meantime, O’Neil alerted Captain Taylor by rushing to the officers’ quarters. Then First Mate Gerry Wood raised the alarm by blowing the ship’s whistle. Just eight minutes had passed since the fire started at 2:38 a.m., but half of the ship’s decks were already on fire.

Donald Williamson, a 27-year-old, arrived on the scene as the first rescuer. Knowing that Noronic was in port, the former lake freighter deckhand wanted to view it after working a late shift at a local Goodyear Tire facility. Williamson came to the sound of the ship’s distress whistle, with people desperately diving into the lake and the fire rapidly spreading. He saw a big painter’s raft close by, so he let it go and moved it to a spot close to the port bow of the ship. He hauled others from the ocean onto the safety of the raft as they dove from the blazing ship.

Ronald Anderson and Warren Shaddock, two Toronto police constables, were responding to a “routine” box call when they turned their “accident” car onto Queen’s Quay just in time to witness the ship erupt in flames as high as the mast. Survivors, some of whom were on fire and many of whom were in shock, quickly approached their ship. Anderson was informed by a passenger about people in the water and on the decks, some of whom were on fire. After taking off his uniform, Anderson dove into the icy, greasy water and started helping Williamson on the raft. Fireboats were called into the rescue effort to pull those off the ship who had leaped into the water. Jack Marks, who later became Toronto’s head of police, was one of those cops.

Some passengers had to be dragged out of their cabins by crew members breaking portholes. The night watchman on the dock saw the flames pouring from the ship just before the whistle blew and called the Toronto Fire Department. Several vehicles were sent to the scene, including a fireboat, a rescue squad, a high-pressure truck, an aerial truck, a hose wagon, a pumper truck, and the deputy chief. Police and ambulances were also called in. At 2:41 a.m., the first fire engine pulled up to the pier.

The ship was now completely engulfed in flames. When the fire started, there were only fifteen crew members on board. Despite this, they were unable to notify all four higher decks of the passengers’ whereabouts, and those who did wake up did so by yelling and sprinting through the hallways. Not many passengers were able to reach E-deck in time to use the gangplanks to escape because the majority of the ship’s stairwells were on fire. A few travellers used ropes to reach the dock. People were seen jumping from the top decks that were engulfed in flames, and several of them fell to their deaths onto the pier below. The scene was later characterized as one of extreme terror. In the insane rush through the passageways, some people were crushed to death. Some others were trapped in their cabins and died of burning or asphyxia. Whistles and sirens were reported to be muffled by the screams of the dying.

The B deck was reached by the first rescue ladder. Passengers hurried over it right away, breaking the ladder in two. A fireboat was there to save the passengers after they were thrown into the harbour. More ladders that reached the C deck remained stable during the rescue operation.

The metal hull was scorching hot after twenty minutes or so, and the decks started to give way and fall in on top of one another. Firefighters had to evacuate after an hour of fighting the fire because Noronic was so heavily flooded with water from the fire hoses that it leaned sharply toward the dock. Then the ship self-righted, and the firefighters went back to where they had been. Over 1.7 million gallons (6.4 million litres) of water had been used at the end.

By five in the morning, the fire was put out, and the remains weren’t recovered until two hours had passed after the wreckage had cooled. Inside the burned-out hull, searchers discovered a macabre scene. In the hallways, firefighters reported discovering skeletons that were burned and embraced. Some dead travellers were discovered lying in bed. Since several skeletons were nearly entirely burned, it is said that forensic dentistry was utilized for the first time to identify remains. Every window’s glass had melted, and the heat had even bent and twisted the steel fittings. All the stairwells had been demolished, with the exception of one close to the bow.

The exact number of people killed in the accident was never established. Estimates for deaths vary widely, ranging from 118 to 139. The majority perished from burns or asphyxia. Some others lost their lives after falling off the upper decks onto the pier or being run over. There was just one drowning. To many’s ire, all 118 of the people who were first slain were passengers. (Louisa Dustin, a crew member, became the 119th casualty and the lone victim from Canada; she eventually passed away from her injuries.)

The House of Commons established an inquiry to look into the incident. The linen closet on deck C was found to be the origin of the fire, although the cause was never identified. It was decided that it was most likely one of the laundry crew members who had dropped a cigarette. Arson was suspected by company executives.

The crew’s incompetence and cowardice—too few of them were on duty when the fire started, and none of them made an attempt to wake the passengers—were mostly to blame for the high death toll. Furthermore, not a single crew member ever called the fire brigade, and a large number of them left the ship at the first alarm. The routes and procedures for evacuation were not disclosed to the passengers. The 36-year-old ship’s structure and design were also discovered to be flawed; fireproof material had been replaced with oiled wood within the cabin, exits were only on one deck rather than all five, and none of the fire extinguishers were operational.

In the weeks that followed the fire, Captain Taylor was praised as a hero. He was one of the last members of the crew to escape the ship after breaking windows during the fire and rescuing stranded guests from their rooms. However, Taylor’s master’s certificate was suspended for a year after the Canadian Department of Transport’s investigation into the accident found that neither Canada Steamship Lines nor Taylor had taken sufficient fire safety precautions. Taylor refuted the claim made by a witness that he had been drinking alcohol at the time of the fire, and other witnesses attested to his regular behaviour.

At the scene, Noronic, which sank to the bottom in shallow water, was partially disassembled. On November 29, 1949, the upper decks were removed and the ship was refloated. It was hauled to Hamilton, Ontario, and discarded there. In 1950, the smaller Huronic, her sister ship, was withdrawn and dismantled. A consequence of new international laws concerning ships carrying wood and other flammable materials was that Canada Steamship Lines gradually phased out the remaining passenger ships from its fleet by 1967. The settlement of Noronic’s civil actions came to just over C$2 million.

Nick Number, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

On Toronto’s Waterfront, a naval museum has Noronic’s whistle on exhibit. On the 50th anniversary of the tragedy, the Ontario Heritage Foundation erected a plaque close to the scene.