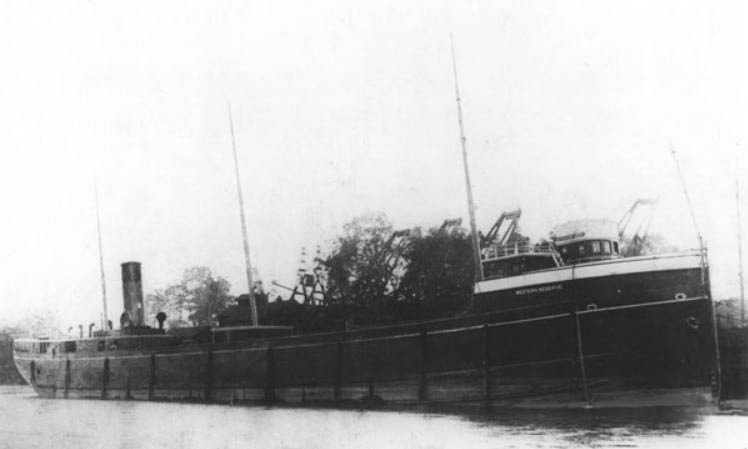

The SS Western Reserve holds the distinction of being the first Great Lakes freighter built with steel plating. Launched in 1890 by the Cleveland Shipbuilding Company, the vessel was commissioned by Captain Peter G. Minch—a visionary in ship design and lake freight transport. Minch played a key role in modernizing bulk cargo shipping on the Great Lakes.

At 301 feet (92 meters) long, with a beam of 41 feet (12 meters) and a draft of 21 feet (6.4 meters), the Western Reserve was the largest bulk carrier on the lakes at the time. Alongside the SS W.H. Gilcher, she was one of the first two lake freighters constructed entirely from steel plate. This innovation allowed her to carry heavier loads more efficiently than traditional wooden steamships.

Thanks to her speed and reliability, she earned the nickname “Inland Greyhound”, as she quickly moved between ports and helped usher in a new era of industrial lake shipping.

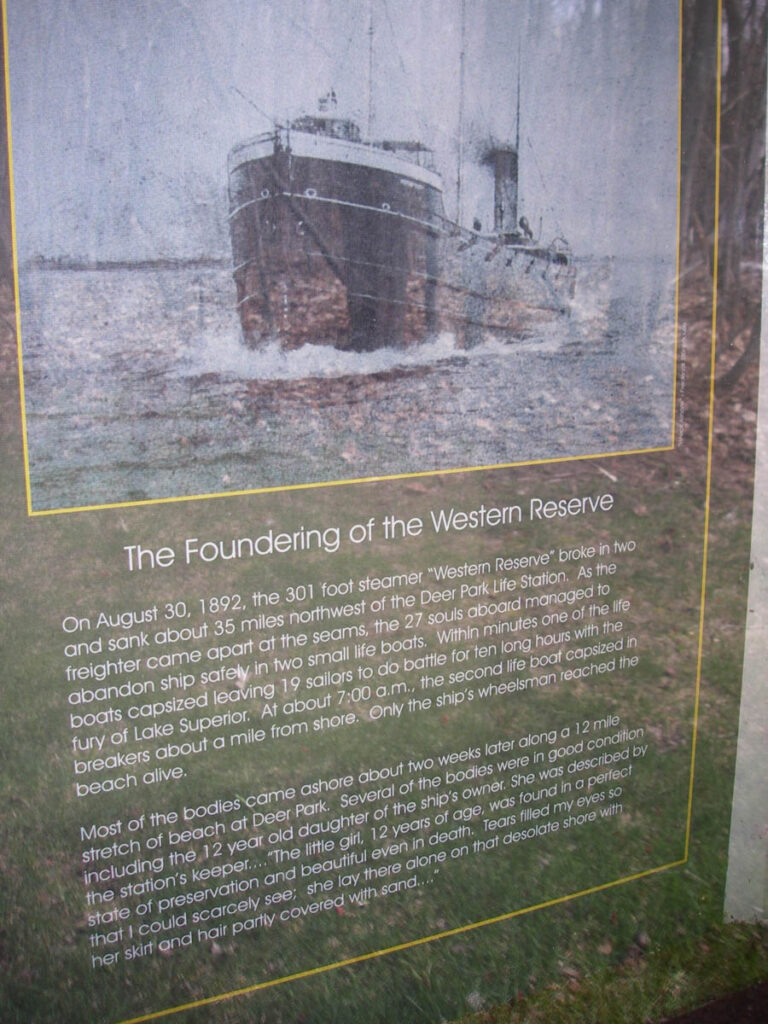

On August 30, 1892, the Western Reserve was making her way upbound through Lake Superior, carrying ballast en route to Two Harbors, Minnesota—a key port for loading iron ore from the nearby ranges. Around 9 p.m., approximately 60 miles (97 km) north of Whitefish Point, the vessel encountered a violent storm. With a sudden and thunderous crack, the ship split in two and sank in less than ten minutes.

All 21 crew members and six passengers managed to abandon ship, escaping in two lifeboats. Seventeen people, including Captain Peter Minch and his family, climbed into a wooden lifeboat. The remaining ten boarded a metal one, which tragically capsized shortly after launch. The wooden lifeboat was only able to rescue two survivors from the overturned metal boat.

That wooden lifeboat stayed afloat through the night until roughly 7 a.m., when it too capsized—just about a mile (1.6 km) from shore. Sadly, everyone aboard drowned, except for wheelsman Harry Stewart. Against all odds, he swam to land and collapsed, soaked and exhausted, somewhere between Grand Marais and Deer Park. Nearly unconscious, he lay on the beach for an hour before crawling ten miles (16 km) to the nearest lifesaving station. Stewart later credited his survival to a thick, tightly woven pea coat, which he said was the one thing that had “alone saved him.”

Experts remain divided on whether the Western Reserve‘s structural design contributed to its catastrophic failure. One theory suggests the vessel succumbed to a phenomenon known as hogging—when a large wave lifts the center of the ship while the bow and stern are left unsupported, causing the hull to snap. Some critics argued the ship’s length exceeded what its design could safely support. Additionally, unlike most large ships of the era which placed the superstructure amidships to reinforce the vessel, the Western Reserve had superstructures located at both ends, potentially weakening its integrity.

Survivor Harry Stewart’s debriefing intensified scrutiny, as his account led to speculation about the steel’s brittleness. At the time, maritime steel was still in its infancy and lacked the flexibility to endure the torsional stresses caused by waves. Notably, the Titanic—which sank two decades later—was constructed with a similar grade of steel, and faced comparable criticisms regarding its vulnerability to brittle fracture.

Just eight weeks after the Western Reserve disaster, her sister ship, the W.H. Gilcher—built during the same period using similar batches of steel—vanished on northern Lake Michigan. The nearly back-to-back tragedies, coupled with the high death toll and the loss of prominent shipowner Captain Minch, sparked a public outcry and investigations. The resulting scandal led to lasting reforms in the standards for steel used in shipbuilding across both the United States and Canada.

The final resting place of the Western Reserve remained a mystery for 132 years. In the summer of 2024, the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society discovered the wreck using their research vessel, David Boyd. Lying 600 feet (180 meters) beneath the surface near Whitefish Point, the ship was found “broken almost straight in half,” with the bow having collapsed directly onto the stern, according to underwater video footage. The society had been methodically searching for the wreck over a two-year period, using side-scan sonar in a grid pattern.

The discovery was kept confidential until March 10, 2025, when the society notified descendants of Captain Minch—distant relatives of the Steinbrenner family—before making the announcement public.