Since the phenomenon of the 1997 hit movie “Titanic” the world, or the western hemisphere at least, has been enthralled with Titanic trivia and still thirsts, seemingly at an ever-increasing rate, for facts about the great ship operated by the renown White Star Line.

Newfoundland has its small claim to Titanic fame. Cape Race received messages from the liner as celebrities aboard the ship clamoured to be the first to send word to the United States via Newfoundland. Icebergs of the size and type that sank the great liner can still be seen near Newfoundland’s coasts.

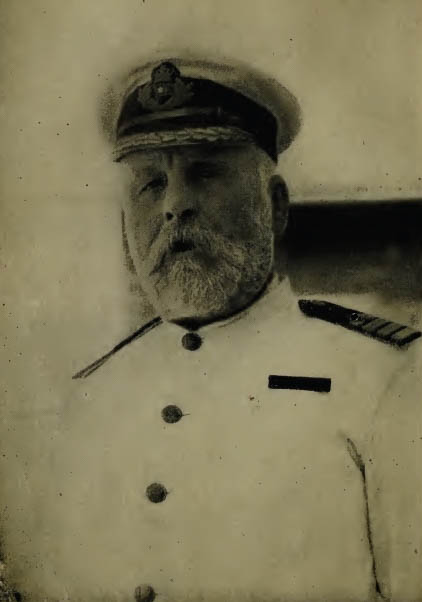

On the night of April 14-15, 1912, the British liner, commanded by Captain Edward Smith, sank after striking an iceberg 500 kilometres (300 miles) southeast of Newfoundland. The disaster, which occurred on the ship’s maiden voyage, claimed the lives of more than 1500 of the 2200 lives aboard.

By 1912, radio was in use on ships and the Titanic sent out distress signals (which were received by Cape Race). Another ship, the Californian, was equipped to receive the signal and was close enough that night to speed to the rescue, but it had only one radio operator and a man has to sleep sometime.

There was no one on duty when the signal came in. Because of the drama of the sinking, the number of lives lost, and the social position of many of the dead, the disaster revolutionized the rules governing sea travel. After 1912, all passenger ships were required to carry lifeboats with enough seats for everyone on board, lifeboat drills were to take place on every passage, radio receivers were operating twenty-four hours a day,

In addition, in 1914 an International Ice Patrol was established and has been maintained ever since, to keep watch over the ice giants of the deep and especially so near the great drilling platforms (like Newfoundland’s Hibernia) of the northwestern Atlantic.

Eighteen years earlier to the loss of Titanic, the White Star ocean liner Majestic rammed and sank a Newfoundland ship. Local tradition has it Captain Edward Smith, who lost his life on Titanic, commanded Majestic at the time. In July 1894, Majestic sped across the Atlantic delivering passengers from England to New York.

On the night of July 30 while off southern Newfoundland, she met thick fog and slowed to half speed. In the inky darkness of three-thirty am, she sliced into a Burin schooner Antelope, drowning Gabriel Mitchell and fatally injuring William Woundy. Antelope, of thirty-four ton, was owned and operated by five Bugden brothers — Captain John, Thomas, Henry, Philip, and Reuben.

In a quirk of fate, all five Bugden brothers were plucked from their schooner’s wreckage and taken aboard Majestic. Mitchell’s body was never found; Woundy died in the liner’s hospital room that night. Majestic’s passenger list shows boxer James J. Corbett who, in 1894, was heavyweight champion of the world. Corbett, who was the first world champ under the Marquis of Queensbury rules (using gloves), was called to a room to view Woundy’s body. According to a story related by Antelope’s crew when they returned to Burin, the boxer was amazed at the arm and upper body size and muscular definition of the tall fisherman.

It is well known that Newfoundland dory fishermen developed barrel chests and powerful arms from their many hours of rowing. Upon seeing Woundy’s body, Corbett remarked, “He must have been a powerful man. I’m glad I didn’t face him in the ring.” Captain E.J. Smith The Bugden brothers were carried to New York, transferred to Halifax, and thence to Burin.

When they arrived home on August 15, they were heartily welcomed by residents. Although they displayed straw hats emblazoned with a White Star banner and wore White Star body sashes, they soon told the sad tale of the loss of Antelope and the death of two crewmates. But not to be confused with Californian (which unfortunately did not help rescue Titanic’s survivors) is the transatlantic steamer California.

The latter, of the Anchor line, cut down the Burin banker Beatrice Vivian on July 12, 1936. The schooner was lying too about twenty-five miles off Cape Race when California hit sending the wooden craft to the bottom in minutes. Captain James Gosling and his twenty-five man crew were all from Burin and area. Unlike the wreck of Antelope, this time there was no loss of life.