Scientists at The Florida Aquarium have again made history, this time becoming the first in the world to reproduce ridged cactus coral or Mycetophyllia lamarckiana in human care. The breakthrough happened over several nights earlier this month at The Florida Aquarium’s Center for Conservation which is located at the Florida Conservation Technology Center in Apollo Beach. The work is part of a collaboration effort to save the Florida Reef Tract from extinction with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Marine Fisheries Service.

“Our resolve to save Florida’s endangered coral reefs continues, and this historic breakthrough by our coral experts, our second in 8 months, provides additional hope for the future of all coral reefs in our backyard and around the globe,” said Roger Germann, President and CEO of The Florida Aquarium. “While our Aquarium remains temporarily closed to the public as we support our community’s wellbeing efforts, not even a global pandemic can slow us down when it comes to protecting and restoring America’s ‘great’ barrier reef.”

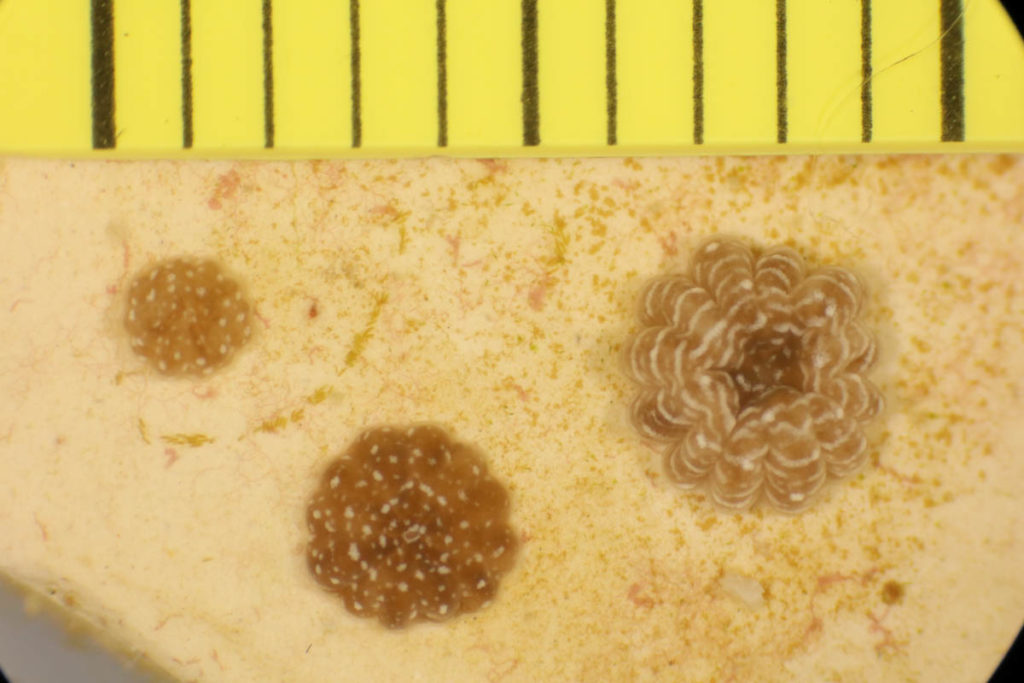

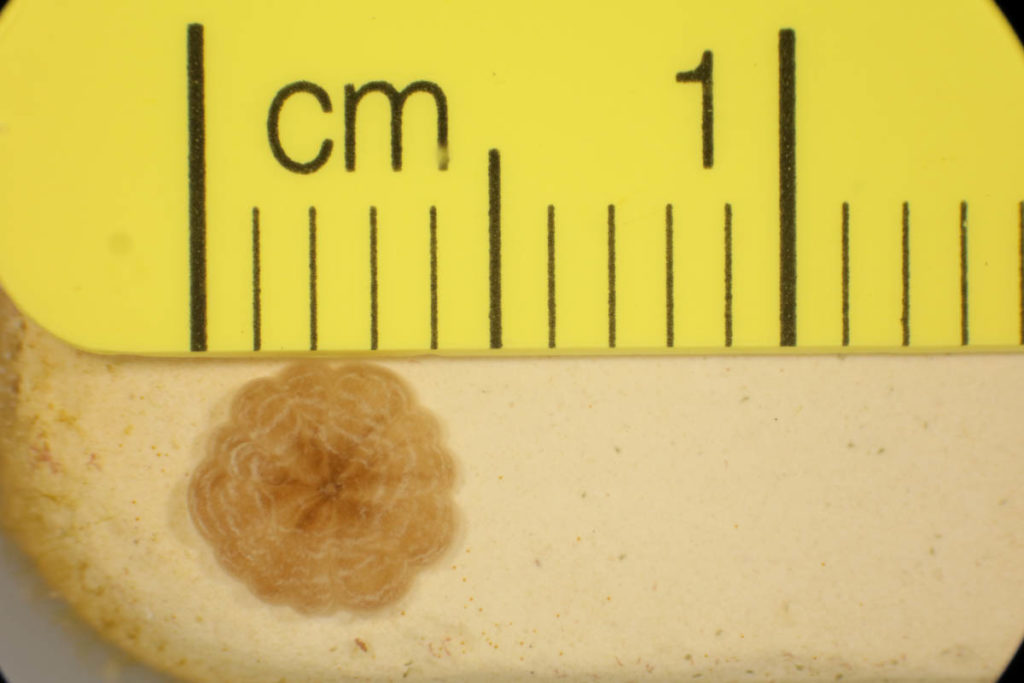

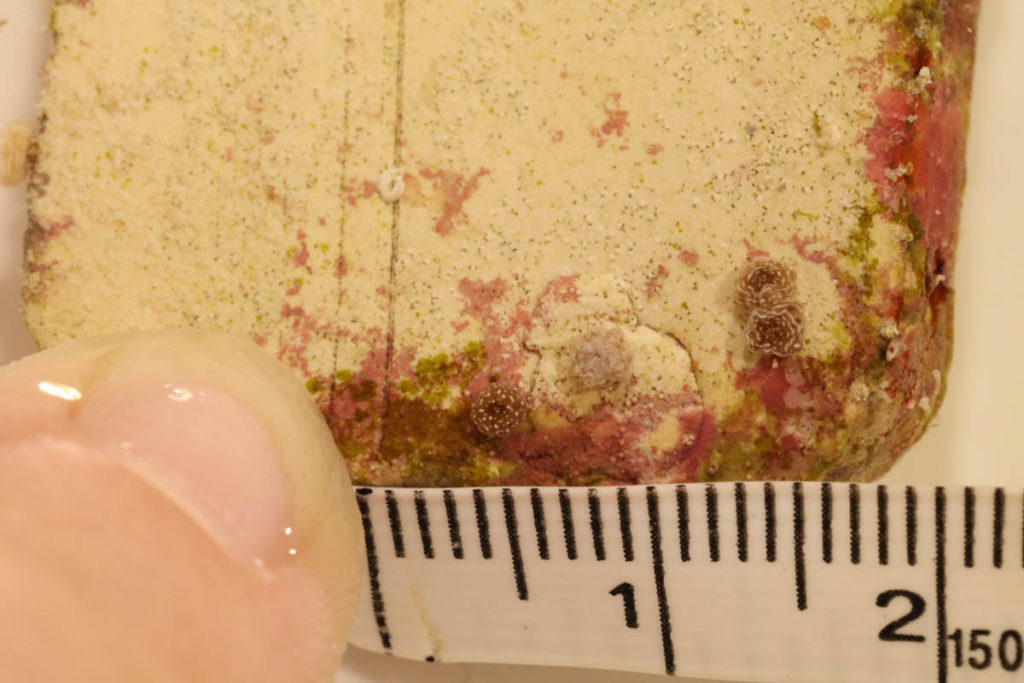

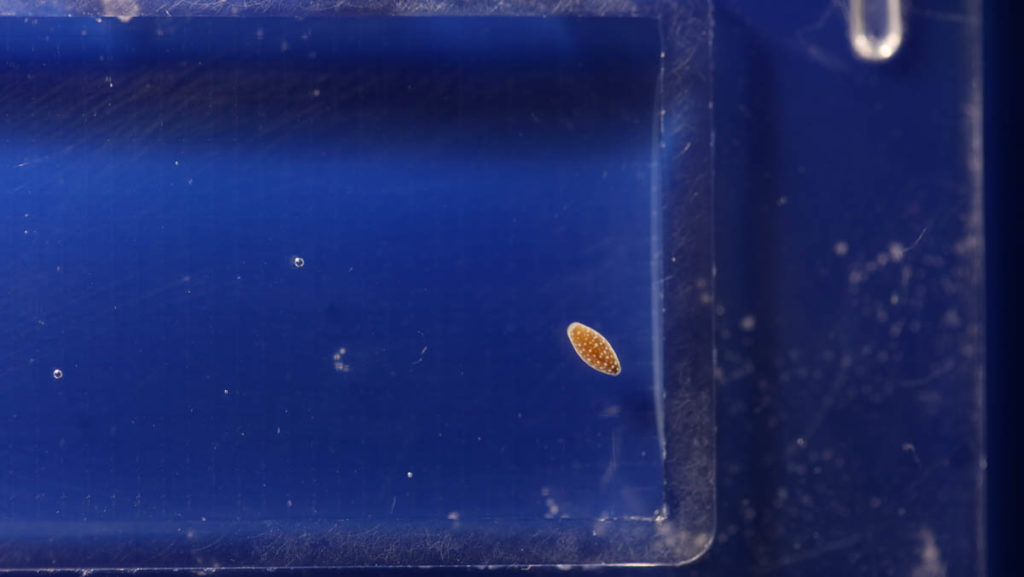

Until this month, the larvae of the ridged cactus coral had never been photographed or measured and the larval release time had never been recorded.

“These advances give us hope that the round-the-clock work we are doing will make a difference to help conserve this species and save these animals from extinction,” said The Florida Aquarium Senior Coral Scientist Keri O’Neil. “To date we have now been able to sexually reproduce eight different species of coral affected by Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease at The Florida Aquarium’s Center for Conservation campus.”

Last year on August 20th, The Florida Aquarium announced a massive breakthrough when it revealed its scientists were the first in the world to be able to get Atlantic Ocean coral to spawn in a controlled laboratory environment.

“The Florida Aquarium is committed to caring for Threatened species of coral and leading critical initiatives that facilitate our ability to restore the Florida Reef Tract” says the Aquarium’s Senior Vice President of Conservation, Dr. Debborah Luke. ‘Our Coral Conservation Program uses a science-based, impact-driven approach to increase the genetic diversity of coral offspring, maximize coral reproduction rates and advance coral health.”

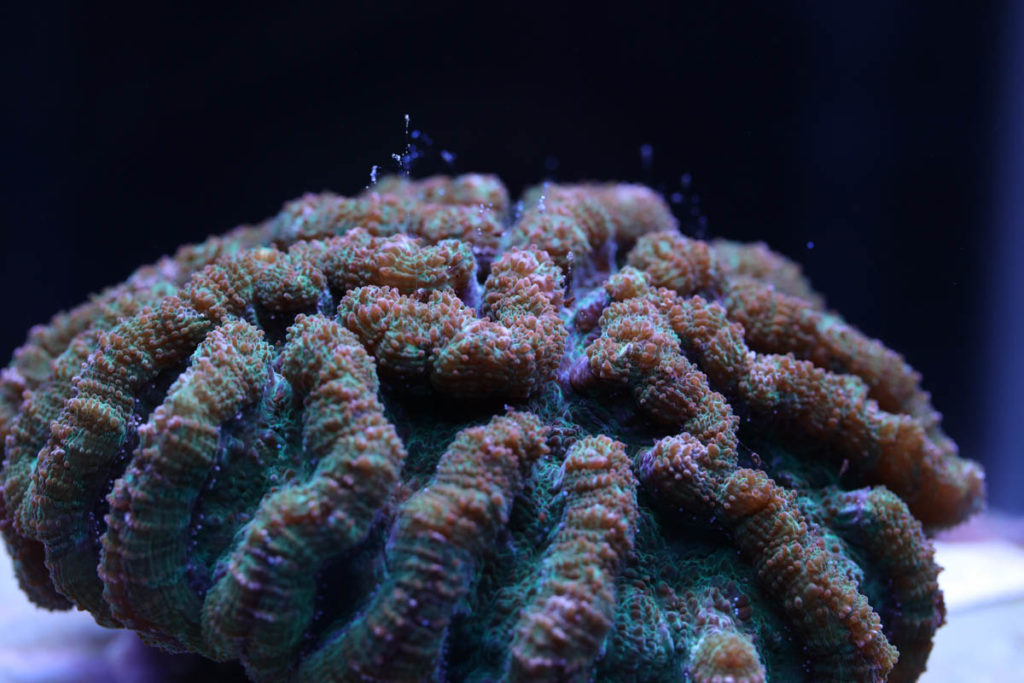

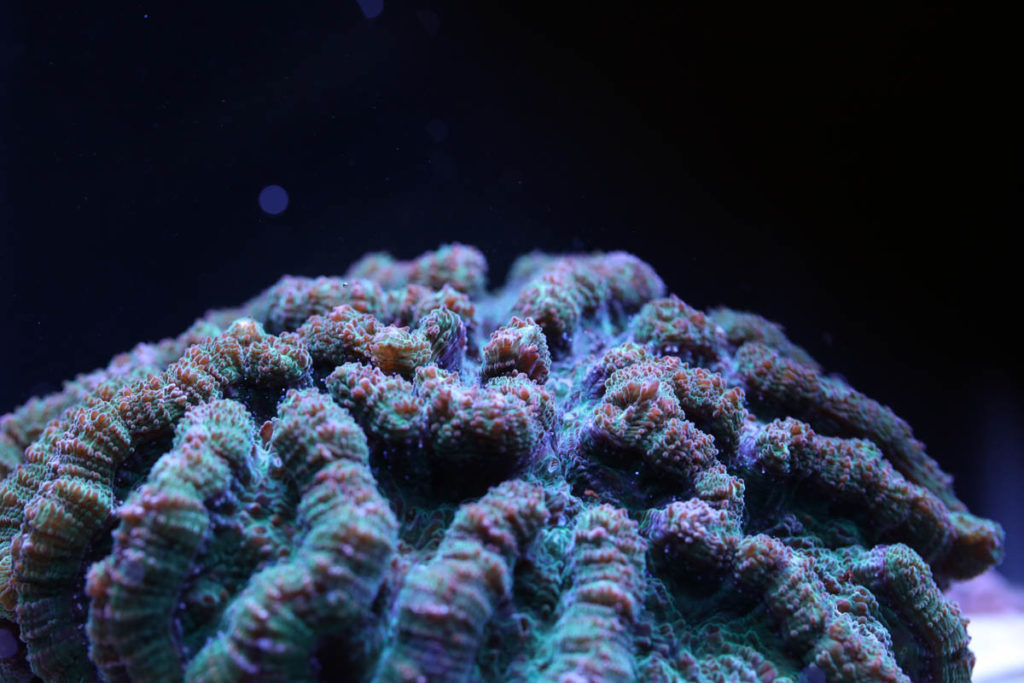

Ridged cactus corals are often brightly colored with ridges that don’t connect in the center. They are a brooding coral, which means their sperm is released into the water, but their eggs are not, and fertilization and larval development occurs inside the parent coral. The corals release a fully developed larvae that swims immediately after release. Brooding corals release fewer and larger larvae, that already carry the symbiotic algae from their parents that is critical for survival. Florida Aquarium coral biologists noted that the larvae of the ridged cactus coral were the largest that they have ever seen and are working to document the entire process.

“They are so unusual that I actually was not sure it was coral larvae,” noted Emily Williams, Coral Biologist.

No one knows how long the corals will continue to release the larvae or how many will be produced, as no one has documented this process before in this species.

“We certainly could not have achieved these groundbreaking efforts without our partners, including the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Great Lakes Dredge and Dock and TECO Energy. Without their coordination, involvement and most importantly, financial investments, the Florida Reef Tract might not survive,” added Germann.

Research activities occurred within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and under permit.