The S.S. Florizel ran aground off the coast of Cappahayden, Newfoundland, 105 years ago, caught in a storm. On February 23, 1918, the SS Florizel set sail from St. John’s on an ill-fated voyage. What was supposed to be a routine trip from St. John’s, Newfoundland to Halifax, Nova Scotia, and then to New York turned tragic. The SOS transmission from the vessel was received by the HM Wireless Station Mount Pearl, which is now the Admiralty House Communications Museum.

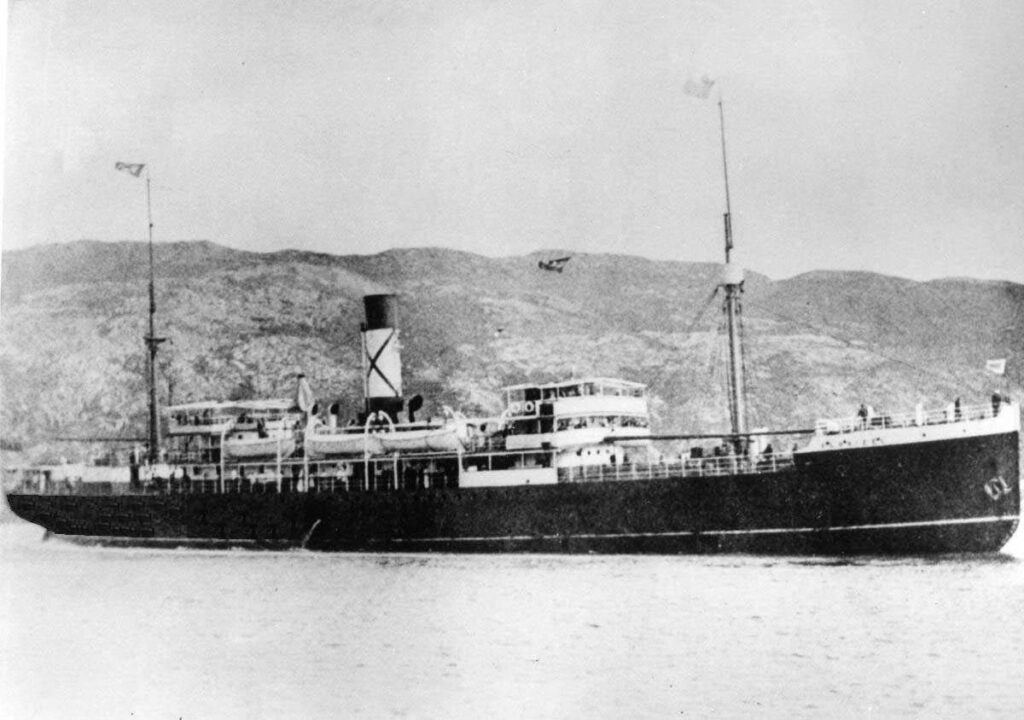

The passenger liner SS Florizel was the flagship of the Bowring Brothers’ Red Cross Line of steamships and one of the world’s first ships specifically designed to navigate icy waters. During her final voyage from St. John’s to Halifax and then to New York City, she sank after striking a reef near Cappahayden, Newfoundland, killing 94 people. Only 44 survived.

The New York, Newfoundland, and Halifax Steamship Company, Limited was operated by Bowring Brothers. The Bowring fleet of ships at the time was given Shakespearean names, such as Florizel, after young Prince Florizel in The Winter’s Tale. Florizel was primarily a passenger liner built for Bowring Brothers to replace the SS Silvia, which had been lost at sea. Florizel was considered a luxury liner at the time of her construction, with 145 first-class accommodations.

Each spring, the vessel was modified to participate in the annual seal hunt, which provided an additional source of income. She was made of steel, with a rounded bow and nearly flat bottom, so she could slide up on an ice floe and break through. Captained frequently by Captain Abram Kean, she assisted in the rescue of sealers during the Great 1914 Newfoundland Sealing Disaster and set numerous records on her numerous voyages to the seal hunt.

During World War I, Florizel was also used as a transport vessel. The sealing steamer could only carry 50 crew and 250 passengers before being converted into a troopship. She carried the first 540 volunteers of the Newfoundland Regiment, the Blue Puttees, in October 1914. She was part of a fleet of 33 Atlantic liners and six Royal Navy warships that formed the largest troop contingent to cross the Atlantic for Europe.

Last Voyage

Florizel left St. John’s on Saturday, February 23, 1918, for Halifax and then New York, carrying 78 passengers and 60 crew. Many prominent St. John’s businessmen were among the passengers. The weather turned bad shortly after the ship passed through the St. John’s Narrows at 8:30 p.m. Because of the ice conditions, the vessel’s log was not deployed. At 10:20 PM, after seeing the Bay Bulls Lighthouse and losing sight of land, none of the three lighthouses south of Bay Bulls were seen. Nonetheless, after eight hours of steaming southward, Captain Martin believed he had rounded Cape Race, maintained his order for full speed, and ordered the final course change to West by South at 4:35 AM.

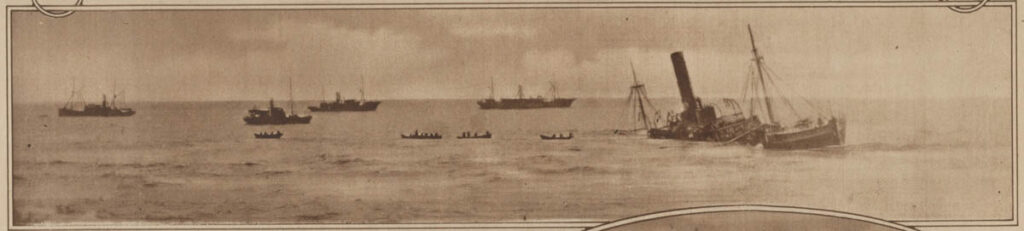

The Captain had only soundings and engine RPM to verify DR position at this point, without the benefit of either the log or lighthouse sightings. Florizel had only travelled 45 miles and was still a long way from the Cape. The sea was white with froth crashing against the rocks at Horn Head Point, and Captain Martin mistook it for ice and crashed into the rocks at 4:50 a.m. The majority of the passengers and crew who survived the initial crash sought refuge in the Marconi Shack, the ship’s least damaged area.

An SOS was sent out and received by the Mount Pearl HM Wireless Station. According to the Evening Telegram, “the Admiralty wireless station at Mount Pearl picked up the first news of the disaster in a radio from the stranded ship: ‘SOS Florizel ashore near Cape Race fast going to pieces.”

The first rescue ships arrived on the evening of February 24 to find no sign of life. When light was seen, the weather had calmed down somewhat, and a rescue attempt was made after the storm had passed. 44 of the 138 passengers and crew survived the initial crash, and the last of the passengers and crew were rescued 27 hours after the ship hit the ground.

After

Captain Martin, who had survived the disaster, was held responsible for the disaster due to a lack of soundings taken during the voyage. His certificate was revoked for 21 months. It wasn’t until much later that Captain Martin was found to be innocent. J.V. Reader, the Chief Engineer, had reduced the vessel’s speed as soon as she left port, defying the captain’s orders to proceed at full speed. This action had resulted in the ship travelling less distance than anticipated. The reason given for Reader’s action was that he wanted to extend the trip to Halifax so that the ship would have to dock overnight and he could visit his family while there.

Medals of bravery were awarded to several crew members of HMS Briton and HMS Prospero who had responded to the wreck; these were given by the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VIII, while he was in St. John’s in 1919.

Betty Munn, a three-year-old passenger, died in the disaster. Heartbroken, her grandfather, Sir Edgar Rennie Bowring, commissioned a replica of the London, England, Peter Pan statue and had it installed on land he donated to the City of St. John’s in 1911 to create the park.