Log driving is the process of using a river’s water to transport logs, or sawn tree trunks, from a forest to sawmills and pulp mills downstream. It served as the primary means of transportation for the early North American and European forestry industries.

The earliest sawmills were often modest, water-powered establishments close to the timber source; once farming was established and the forests had been cleared, these might have been transformed into grist mills. Later, log drives floated the logs down to larger circular sawmills that were built in a river’s lower reaches. The logs may be tied together to form lumber rafts in the wider, slower sections of a river. Masses of individual logs were driven down a river like vast herds of cattle in the wilder, smaller sections where rafts could not pass. By the 16th century, “log floating” (timmerflottning) had started in Sweden, and by the 17th century, “tukinuitto” had started in Finland. The overall length of routes that float timber in Finland was 40,000km.

The log drive was a single stage in a more extensive process of producing lumber in isolated locations. In an area where winters are snowy, the annual procedure usually started in the fall when a small group of workers carried tools upstream into the wooded area, cleared a clearing, and built rudimentary structures for a logging camp. When the camp froze in the winter, a larger workforce moved in and began cutting trees. They cut the trunks into 5-meter (16-foot) lengths and then pulled the logs to the riverbank using oxen or horses over iced paths. They fitted the planks onto “rollways.” The drive started when the logs were rolled into the river as the water levels rose and the snow thawed in the spring.

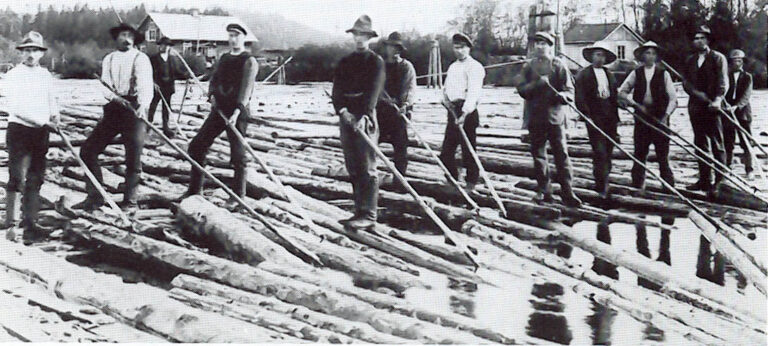

Men known as “log drivers” or “river pigs” were required to direct the logs so they drifted freely along the river. Usually, the drivers were split up into two groups. The “beat” or “jam” crew consisted of the more skilled and agile males. They kept an eye on the areas where logs were most likely to jam, and when one did, they made an effort to reach it fast and remove the important logs before a lot more logs piled up. The river would continue to pile on more logs if they didn’t, creating a partial dam that might cause the water level to rise. Upriver, millions of board feet of lumber may back up for miles, taking weeks to break up. If the timber was forced deep enough into the shallows, part of it would be lost.

Strong muscles, tremendous agility, and a basic understanding of physics were necessary for this position. With the drivers standing on the sliding logs and rushing from one to another, the jam crew job was extremely risky. Numerous drivers were killed as they fell and were crushed by the logs.

Every crew had a seasoned leader who was frequently chosen for his combat prowess in order to manage the powerful and careless members of his team. The “walking boss” oversaw the entire drive, moving from location to location to manage the different squads and keep logs passing trouble locations. Driving close to a saloon frequently resulted in a chain reaction of inebriated staff issues.

Uncredited photographer for the Brown Bulletin, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

They were followed by a bigger contingent of less experienced men who pushed along the straggler logs that were lodged in trees and on the banks. Wading in freezing water took up more of their time than balancing on shifting logs. We referred to them as the “rear crew.” From the bank, several men joined them in moving logs away with pike poles. Others used oxen and horses to haul in the logs that had wandered the farthest onto the flatlands.

Stumbling logs trapped in branches and on the banks were pushed along by a bigger group of less experienced guys who came up the back. Wading through frigid water took up more of their time than balancing on shifting logs. They were referred to as the “rear crew.” They were joined by other men from the bank who used pike poles to push logs aside. The logs that had wandered farthest out into the flats were pulled in by others using horses and oxen.

A straight, consistent river with steep banks and a steady flow of water would have been ideal for wood drives. Because wild rivers weren’t that, men dynamited problematic rocks, cleared away fallen trees that would snag logs, and constructed banks where necessary. On smaller streams, they constructed “flash dams” or “driving dams” to regulate the water flow, allowing them to unleash water to drive the logs down whenever they desired.

A mark known as a “end mark” was applied to the logs by each forestry company. A timber mark could not be erased or altered. A log boom caught the logs at the mill, where they were sorted by owner before being cut into pieces.

Because logs may occasionally flood the entire river and make boat movement hazardous or impossible, log drives frequently clashed with navigation.

For the most sought-after pine lumber, floating logs down a river worked well because of its ability to float. However, some pines were not close to drivable streams, while hardwoods were denser and not buoyant enough to be driven readily. With the construction of railroads and the usage of trucks on logging roads, log driving became less and less required. However, in certain isolated areas without such infrastructure, the practice persisted. As environmental laws changed in the 1970s, the majority of log driving in the US and Canada came to a stop.

BERLINHISTORY, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Because logs may occasionally flood the entire river and make boat movement hazardous or impossible, log drives frequently clashed with navigation.

For the most sought-after pine lumber, floating logs down a river worked well because of its ability to float. However, some pines were not close to drivable streams, while hardwoods were denser and not buoyant enough to be driven readily. With the construction of railroads and the usage of trucks on logging roads, log driving became less and less required. However, in certain isolated areas without such infrastructure, the practice persisted. As environmental laws changed in the 1970s, the majority of log driving in the US and Canada came to a stop.

“The Log Driver’s Waltz” is a well-known folk song in Canada that extols the virtues of a log driver’s dancing.

The 1974-issued and 1989-withdrawn Canadian one-dollar banknote depicted the Ottawa River, with Parliament Hill rising in the distance and log driving occurring in the foreground. This banknote belonged to the Bank of Canada’s fourth series of “Scenes of Canada” banknotes. The logs shown on this banknote would have been intended for other mills downstream or for a half dozen pulp, paper, and sawmills close to the Chaudière Falls, which are directly upstream from Parliament Hill.