Posidonia oceanica, a species of seagrass, is often referred to as “The lungs of the Mediterranean” because the seagrass meadows absorb carbon dioxide and output oxygen at twice the daily rate of tropical forests.

Seagrasses store an estimated 27.4 million tonnes of carbon each year, burying it in the soil below. And unlike forests that hold carbon for about 60 years then release it again, seagrass ecosystems have been capturing and storing carbon since the last ice age. With seagrass meadows disappearing at an annual rate of about 1.5 per cent, 299 million tonnes of carbon are being released back into the environment each year, according to research published in Nature Geoscience (DOI: 10.1038/ngeo1477).

In addition to storing carbon, seagrasses protect coastlines from floods and storms, filter out sediment, and serve as a vital habitat and nursery for fish, crustaceans and other commercially important species.

In the past century, 29 per cent of seagrass has been destroyed globally by coastal development, fishing by otter-trawling, pollution, and now climate change.

Unique to the Mediterranean Sea, Posidonia oceanica meadows are identified as a priority habitat for conservation under the European Union’s Habitats Directive (Dir 92/43/CEE) and Catalunya has banned otter-trawling over Posidonia beds. Yet the destruction of this slow growing species continues at an alarming rate.

On the Costa Brava, where Kenna Eco Diving has been researching Posidonia for the past 13 years, we have witnessed a loss of an estimated 25 per cent of the Posidonia meadows. Seagrass-friendly moorings for boats are installed during the peak summer months, but boaters are not penalised for anchoring in the Posidonia beds, destroying hundreds of years of growth in minutes.

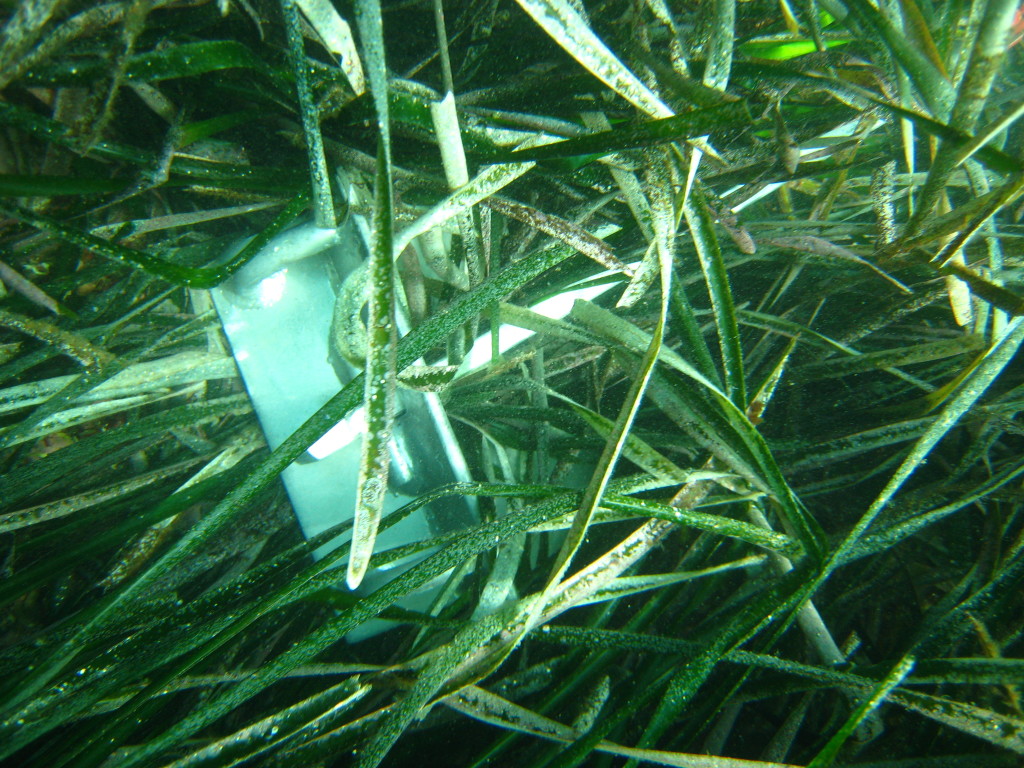

As Posidonia meadows are being destroyed the Posidonia pipefish, a relative of the seahorse, is suffering. The Posidonia pipefish is perfectly adapted to the seagrass habitat and has evolved to resemble a blade of seagrass. It is virtually impossible to see unless it swims above or outside the seagrass beds – a rare occurrence as it is a poor swimmer and rarely ventures out of the safety of the Posidonia meadows, spending it’s time head down within the shoots searching for tiny shrimps to eat. It is totally dependent on the Posidonia habitat for daily food and shelter, and as a seasonal breeding ground and nursery.

Posidonia and the pipefish are just two of the key species being studied by volunteer scuba divers assisting Kenna Eco Diving with underwater surveys for the SILMAR Project. Volunteering with Kenna Eco Diving on the Costa Brava is open to international divers who spend a few weeks or months, during May to October, collecting key species data for the SILMAR Project, aimed at conserving Mediterranean coastal biodiversity via public participation.

Please sign our petition asking for anchoring to be regulated in Posidonia meadows and contact us if you would like to volunteer this summer!